Mali: juntas and jihadists jeopardise journalists

by Peter Chilson

In 1988 Clarence Roy-Macaulay, a Sierra Leonean freelance journalist based in Freetown, the capital, gave a couple of visiting foreign journalists a crash course in national politics. At the time a good-natured and famously gargantuan career soldier named Joseph Saidu Momoh was president and the country was at peace. Sierra Leone’s nightmare of civil war, child soldiers, random amputations and blood diamonds—one of the most horrific human rights stories in the history of modern independent Africa— was four years away. Still, even in an empty hotel dining room Mr Roy-Macaulay did not feel free to speak his mind without precautions. Eyes skirting the room, he leaned across the table and spoke in a hushed voice.

“Momoh’s government is a hollow shell,” he said. “He will fall soon. He is not a strong leader.” He tapped the table with his index finger. “When he leaves, this country will fall apart.”

One reporter at the table shot back. “Well, Clarence, you have the contacts, you’ve been watching this government for years, why don’t you write the story?”

Mr Roy-Macaulay at that time was a thin, wiry man in his 40s, with an intense gaze, a semi-permanent frown, and close-cropped greying hair. He spoke precise and fast English and had a way of raising his eyebrows like quote marks when he was annoyed. “Are you crazy?” he hissed at the reporter. “If I write that story, they’ll kill me. They’ll kill my wife and daughter. As a reporter, I am more valuable alive than dead.”

Mr Roy-Macaulay was right about Joseph Momoh. But, more importantly, his impatient words over dinner underlined the dangers African journalists face in covering their own countries. For example, in Côte d’Ivoire, after contested elections in 2011, police assaulted a reporter for La Nouvelle newspaper in June 2012 while he was covering a police union protest over salaries. On September 7th, a government minister’s security detail beat an Ivorian journalist working for Le Nouveau Courrier while he was trying to report about this minister’s divorce. Then in early September 2012, the government banned six opposition newspapers allied with the government of former president Laurent Gbagbo. The decision was unrelated to the attacks on the two journalists, but under the weight of international criticism, the government revoked the ban on September 17th.

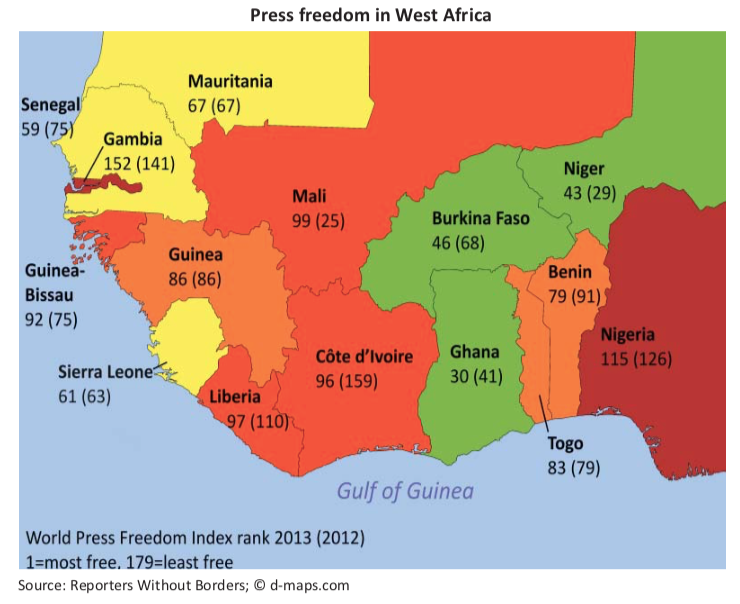

Meanwhile, covering Mali is as complex as the reasons behind the March 21st 2012 coup, even more so since the arrival of French troops in January 2013. The World Press Freedom Index, published in January 2012 by Reporters Without Borders, praised Mali as one of the few African countries “where respect for freedom of information has taken a firm hold”. (This year’s index reflects a large decline in press freedom—99 from 2012’s 25.) Indeed, Mali threw off 27 years of military dictatorship in 1991 and by 2012 had emerged as an African model of democracy and artistic achievement. Mali’s music, cinema and publishing industries had become the envy of the continent. Dozens of newspapers thrived in Bamako, the capital.

But all of this came crashing down in March 2012 when the military coup ended 21 years of democracy and ousted the elected government of President Amadou Toumani Touré. Since then Malian journalists have been kidnapped and beaten and their lives have been threatened. Malian soldiers have sacked newspapers and radio stations. Many newspapers have ceased publication, though it is not yet clear how many have folded definitively.

The military has not spared the international press either. On several occasions throughout the spring and summer of 2012, Mali’s military briefly detained foreign wire service reporters in Bamako. The worst attack occurred on March 28th 2012, one week after the coup. That night, Omar Ouahmane, a reporter for the French radio service France Culture, was tied to a tree outside his hotel in Bamako and left for hours. His offense: he had interviewed President Touré, who was still in hiding. Soldiers threatened to kill Mr Ouahmane before an officer ordered his release.

Most recently, during the week of January 21st 2013, the Malian army banned foreign and local reporters from Sévaré in central Mali, where local residents had reported seeing Malian soldiers killing Tuareg and Arab men suspected of being allied with the rebellion. These reports have not been verified, though similar unconfirmed killings occurred in the town, home to a major Malian military base, in April 2012.

Ironically, the government news agency, Agence Malienne de Presse et de Publicité (AMAP), remains one of the best news sources in Mali. It has managed against all odds to protect some of its independence. This came to light on April 30th 2012 and the days following, when a disgruntled paratrooper regiment loyal to President Touré attempted to reverse the March military coup and oust the new junta. For five days fighting raged around the national television station and airport until soldiers loyal to the junta put down the paratrooper revolt.

The junta’s leader, Captain (now General) Amadou Sanogo, an American- trained intelligence officer, claimed on national television that the mutinous paratrooper unit had help from foreign mercenaries, possibly, he said, from Côte d’Ivoire and Burkina Faso. The governments of both countries had criticised the Sanogo junta for overthrowing President Touré and threatening democracy. Yet after weeks of rumours and accusations, no mercenaries were arrested and AMAP reported through national radio and the government newspaper, l’Essor, that there was no evidence of mercenary involvement in the countercoup.

“We are not going to confirm such rumours until we have evidence,” said Souleymane Drabo, AMAP’s director, in an interview in May 2012. “And there is no evidence of foreign mercenaries coming from Côte d’Ivoire or Burkina Faso. The claim is false.”

Despite the determination of AMAP and reporters from Mali’s independent press, reporting on Mali’s crisis remains dangerous, particularly for Malian journalists. On July 2nd 2012 masked men abducted and beat Abderahmane Keita, editor of the Malian newspaper L’Aurore. The identity of the kidnappers and the motive for the abduction are not clear. Nonetheless, the men left Mr Keita bleeding by the side of a road near the national airport. He survived.

Then ten days later masked gunmen entered the offices of l’Indépendent, firing their guns in the air. They abducted an editor, Saouti Haidara, and beat him badly. Members of his staff found him later that night by the side of a road near the national stadium. He was bleeding but alive. The kidnappers have not been caught or identified, but according to Reporters Without Borders, Malian intelligence officers had detained Mr Haidara in May because of an article he had published raising concerns about security in Bamako.

In July 2012 the United States embassy in Bamako said the attacks on Malian journalists threatened “Mali’s strong tradition and exemplary record of press freedom”. This was followed by condemnation from Reporters Without Borders. “Long an example of freedom of information in Africa, Mali has experienced a constant and dramatic deteri- oration since a military coup in March and the occupation of the north…by various armed groups,” said the watchdog group in an August 8th 2012 statement on its website.

In the north of Mali, a 200,000-square-mile area ruled by al-Qaeda-affiliated jihadist groups, the situation is even worse than in the government-controlled south. In August 2012 jihadists in the city of Gao attacked radio reporter Malik Maiga Aliou while he was on air. They dragged him from his studio, beat him, and left him at a local cemetery. He survived.

The great challenge in covering the war in Mali since the March 2012 coup has been confirming reports of human rights abuses under sharia law in northern Mali. The international press, such as The New York Times, has published eyewitness accounts based on telephone interviews describing amputations for thieves, stoning of adulterers and lashings of people caught with alcohol or cigarettes, or listening to music. Couples bearing children out of wedlock have been stoned to death. AMAP and its informal network of local correspondents, many of them anonymous, reporting from the northern cities of Timbuktu and Gao, have provided some of the most reliable reporting of these incidents.

“We still have people in place in the north,” Mr Drabo said. “And they are taking real risks to get information out when they can. We are not asking them to take risks, but they are.”

The Western press has shied away from covering events in the north for fear of kidnapping. Among the few Western journalists, Paul Mben, of the German weekly news magazine Der Spiegel, has visited the occupied north, travelling by bus to the northern cities of Gao and Kidal in October 2012. Gao, he reported, “has become a lifeless place” where the streets are patrolled by Islamic police who have banned even the public drinking of tea.

Through national radio and the l’Essor newspaper, the AMAP agency is also closely covering the plight of Mali’s refugees, a story that the Western press covered sporadically last summer but has largely ignored since. Close to 600,000 people have fled the fighting in Mali and a devastating famine since January 2012, including about 100,000 displaced within Mali itself. AMAP reporters have followed the story in refugee camps in Burkina Faso, Niger and Mauritania. They have reported on the camps’ overcrowded conditions, food shortages, gunrunning and the risk of jihadist infiltration into these refugee sites. Burkina Faso has reinforced its northern border with Mali with 2,000 additional troops.

With the January 2013 arrival of French troops, the story in Mali is getting even more international attention. On January 11th soldiers held a team of German journalists with Der Spiegel as they were travelling north of Bamako to get close to the fighting between French troops and jihadists in central Mali. French and Malian military authorities have allowed reporters into Malian frontline towns, such as Diabaly, recently abandoned by jihadist forces. But news images of actual fighting have not yet appeared.

Yet few African reporters know the risks of covering war and political strife like Clarence Roy-Macaulay. He is still the Associated Press (AP) reporter in Sierra Leone, a post he has held for more than 25 years. In 2006 the AP gave him its highest honour, the Gramling Spirit Award, for “excellence and distinguished service”.

Mr Roy-Macaulay started his career in the Sierra Leone government information ministry and served as an information officer in embassies across Europe, including Sierra Leone’s mission in Moscow. He moved on to freelance work and editing newspapers. He survived the civil war and is still reporting, perhaps because of a talent for self-preservation reflected in what he told two foreign colleagues at that memorable dinner in 1988.

In those days Mr Roy-Macaulay could often be seen driving in Freetown and the neighbouring countryside in his prized possession, a yellow four-door Russian Lada sedan. He called the car his “office”. He kept all his notebooks, a camera, and any documents collected for stories in the Lada’s trunk. “This way,” he said, “I can get rid of my notes very fast if I have to. You never know who is going to come looking for you.”