Africa’s megaliths

From Sudan to South Africa, archaeologists are only just beginning to properly explore the remnants of Africa’s magnificent ancient past

“Pyramid diving” is an activity that you’d be forgiven for thinking was a dangerous extreme sport dreamed up by a reckless millennial. In fact, it refers to a new archaeological endeavour in the Nubian desert sands of Sudan. In early July 2019, the National Geographic television channel premiered a documentary about exploration of an obscure pyramid in Nuri, northern Sudan. Below the 2,300-year-old pyramid are tunnels and chambers that lead to the last resting place of a pharaoh named Nastasen. The problem for inquisitive archaeologists of earlier times – not to mention grave robbers – was the underground labyrinth flooding with water seeping through from the adjacent Nile River. “I think we finally have the technology to be able to tell the story of Nuri, to fill in the blanks of what happened here,” egyptologist and underwater archaeologist Pearce Paul Creasman told a National Geographic editor, Kristin Romey, in July.

Creasman, a professor at the University of Arizona, is working with National Geographic to discover the secrets of this ancient African civilisation that probably rivalled the Egyptians and the Mesopotamians in advanced intellect, creativity and governance. Just weeks before, the intrepid professor had donned wetsuit and goggles, descended a flight of steps and plunged into the now watery tomb of Nastasen, the pharaoh of the Kingdom of Kush from 335 BC to 315 BC. “It’s a remarkable point in history that so few know about. It’s a story that deserves to be told,” he said. Visibility in the water at the entrance to the subterranean tunnel was zero due to the sand Creasman stirred up, but eventually he discerned stone features in the light of his torch as he swam through a series of chambers. Suddenly, he spotted what looked like a royal sarcophagus. It looked unopened and undisturbed. A glimpse inside that tantalising stone coffin must wait until 2020 when the excavation team hopes it will be logistically possible to open it.

For the moment, Creasman’s focus is on securing the safety of the lengthy piped air-supply system to divers because the tunnels are too narrow for oxygen tanks, as well as locating and removing easily accessible burial artefacts before teams start to excavate through the sediment and fallen roof stones. Given enduring public fascination with the likes of Egypt’s young pharaoh Tutankhamun, the opening of Nastasen’s sarcophagus has the potential to be a momentous global event – and could even be a turning point in international perceptions of Africa. The outside world’s view of Africa – and particularly its cultural heritage – is notoriously limited, not to say biased. “There is a way of seeing Africa in terms of poverty and conflict – the coup, the war, the famine, the corruption – which has become a kind of shorthand for the continent,” BBC World News presenter Zenaib Badawi observed during an African history series that she presented in 2017.

This pervasive view – in the West and East – is informed by current events and takes little account of the rich heritages of earlier civilisations on the continent. Reasons for this include a paucity of paper-and-ink historical records and a legacy of European colonial attitudes of superiority and “civilising” zeal that swept away the memory and markers of the past. This situation was reflected in an infamous 1965 remark by the prominent British historian Hugh Trevor-Roper, who declared that Africa is “no historical part of the world; it has no movement or development to exhibit”. He went on: “There is only the history of the European in Africa. The rest is largely darkness, like the history of pre- European, pre-Columbian America. And darkness is not a subject for history.” Most scholars nowadays agree Africa does indeed have “history”; some argue that comparing it to European history is poor academic methodology.

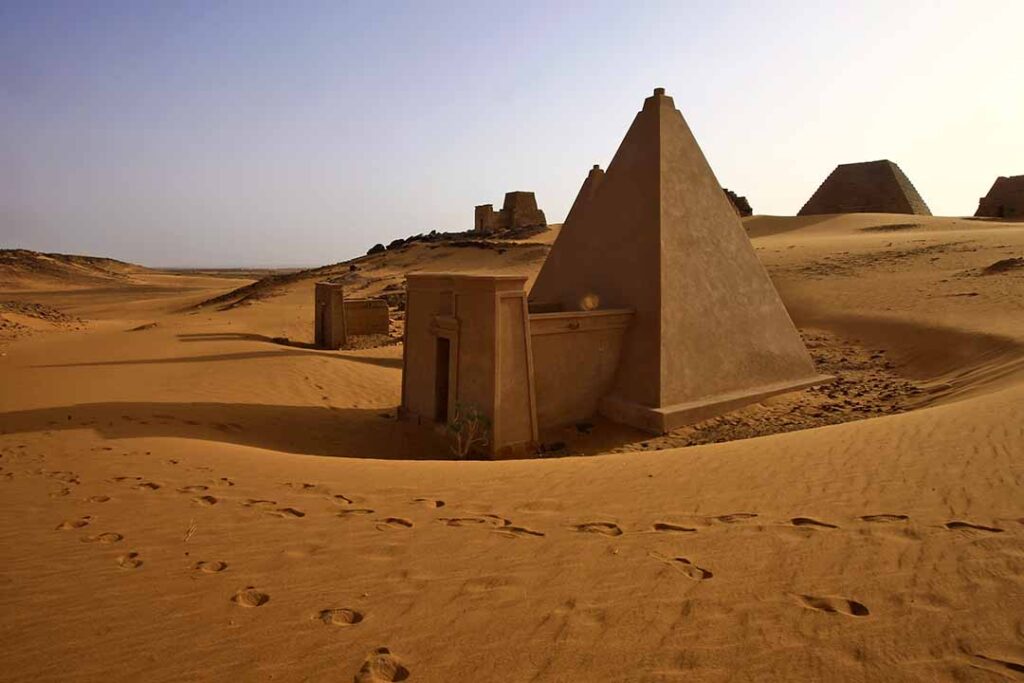

Much of this history is slowly being revealed at ancient megalithic sites such as the pyramids of Sudan, the fabled Great Zimbabwe, Mapungubwe in South Africa and the Walls of Benin. Many of these sites are relatively unexcavated and under-explored and we can only wonder what revelations about ancient Africa await future generations. Sudan actually has many more pyramids than Egypt – about 300 of them at various sites in Nubia in the Nile Valley. The earliest examples date back to 2,500 BC and they were built by people who belonged to three great Kushite kingdoms. Made of sandstone and granite, sometimes looming black against the pale desert sand, they are generally smaller and steeper than Egyptian pyramids. The Kushites were heavily influenced by Egyptian culture, commerce and the military – and competed with them; Kushite pharaoh Piye and his successors ruled Egypt for more than a century.

Unesco has described Sudan’s pyramids as masterpieces “of creative genius demonstrating the artistic, political and religious values of a human group for more than 2,000 years”. With such rare antiquities, Sudan should be a modern tourist magnet, with foreign cash bolstering the struggling economy. But decades of violent regional conflict have deterred all but the bravest tourists. The Tripadvisor website, for example, carries just eight visitor reviews of the Nuri necropolis from the past five years – most of them enthusiastic about the visual experience and complete lack of other tourists, but lamenting the abandoned and crumbling state of the sites. Similarly with Axum in neighbouring Ethiopia. The ancient city was the historic capital of the Aksumite Kingdom, a great naval and trading power that ruled a million square miles of the Red Sea region from about 400 BC through to the 10th century, and it is crammed with remarkable relics.

The Aksumites had their own written language, Ge’ez, and a distinctive architecture that incorporated giant obelisks, known as steles, the oldest dating back to about 5,000 BC. Christian and Muslim influences permeate through to the present day, while the place is trapped in something of a time warp, with camel caravans still to be seen setting off into the surrounding desert. The stele park in Axum contains an awesome collection of these towering stones, marking royal burial sites. Skilfully carved with doors at the base and storeys of windows above, stele look like sculptures of skyscrapers – though the idea of such buildings lay many centuries into the future. The tallest, the 33 m Great Stele, lies in pieces; it probably fell and was shattered during construction. In 1937, the invading Italian army removed the 24.6m-high Obelisk of Axum and installed it in Rome; it was returned in 2005 and re-erected in the park.

Ethiopians are adamant that the biblical Ark of the Covenant is safe and sound in Axum – in a small chapel built in the 1960s beside the ancient church of Our Lady Mary of Zion of the Ethiopian Orthodox faith. Also in Axum are the largely unexcavated 4th century Ta’akha Maryam and 6th century Dungur palaces. There is also a great pool reputed to be the bathing spot of the Queen of Sheba, who is said to have lived here. Other antiquities are the Ezana Stone, written in Ge’ez, Greek and Sabaean, and King Bazen’s Tomb, one of the earliest of all African megalithic structures. Then there are the astonishing stone-hewn churches of Lalibela and the secluded monasteries of Lake Tana, some of which are said to have links to early Christianity. With its historical marvels, Ethiopia has the potential for a tourism industry to rival Egypt’s.

But the decades-long conflict with neighbouring Eritrea, the economic and societal devastation of the communist Derg regime of the 1970s and 80s and proximity to the Sudan conflicts have severely constricted Ethiopia’s tourism dividend. However, recent signs of political commitment on various sides to resolving conflict in the Horn of Africa might see the situation change. Indeed, a flowering of peace and democracy across the entire continent might open eyes to an Africa different to the one routinely portrayed internationally. Great Zimbabwe is well known, such is its magnificence, but it might be regarded as something of a megalithic “outlier” when African heritage is considered. Few people outside Zimbabwe know of the spectacular ruins of the Kingdom of Khami to the south, near Bulawayo. These were built from 1450 onwards and contain the longest-known decorated wall in sub-Saharan Africa.

In South Africa, there are the remains of the 11th century Mapungubwe civilisation in Limpopo province, which pre-dates Great Zimbabwe, which have only been partly investigated in recent decades; the site was kept hidden during the apartheid years. This community had a sophisticated trading economy, powered by gold and ivory, which is epitomised in the golden rhino sculpture that has become an icon of democratic South Africa. These and other lights of ancient African history and culture are beginning to shine on the international horizon. A recent claim that the oldest man-made structure on Earth has been located in South Africa’s Mpumalanga province might attract some disbelief. In 2003 researchers announced the discovery of a meticulously arranged rock circle, dubbed “Adam’s Calendar”, which apparently constitutes a heavenly timepiece.

It is said to be 75,000 year’s old – far older than either Stonehenge and the Great Pyramids of Giza. The truth of these claims is to be determined. Yet this strange place will surely eventually stake a claim in the world’s consciousness of its history too, along with the pyramids of Nuri, the Stele of Axum, the Nok Caves of Togo and a myriad other megalithic marvels across Africa.