Vast mineral wealth has fuelled the on-going conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Its forests and mountains are home to minerals such as tin, tungsten, tantalum and gold which are used in cellphones, computers, medical devices and automotive parts. Rogue militias have hijacked chunks of this mineral trade and used the profits to fund their activities. To stop the funding of these armed groups the United States (US) Congress passed legislation. Nicholas Long looks at why this law may have caused more harm than good.

In the past ten years many reports have blamed mineral wealth and its uncontrolled trade for bankrolling armed groups and inflaming the brutal conflicts in the DRC.

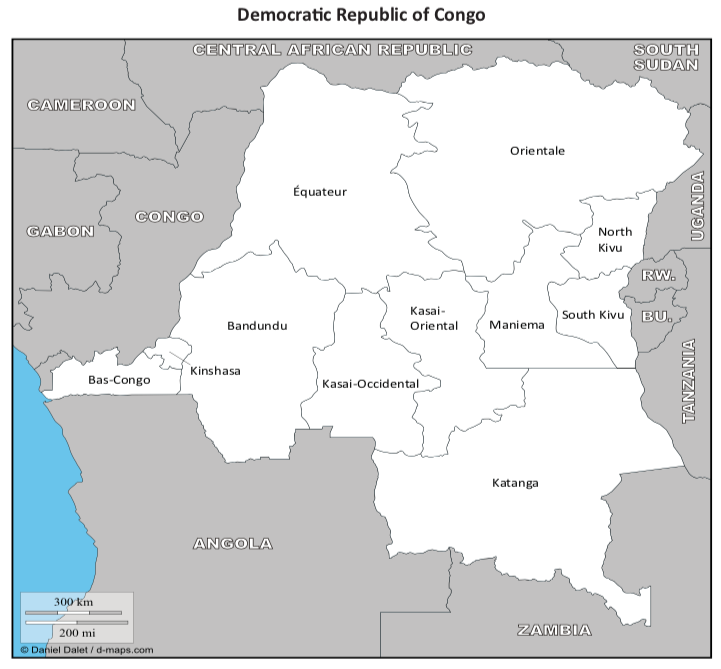

Various measures have been tried to cut off that funding. Individuals and companies have been sanctioned. By the end of 2009, the Congolese army, with help from the United Nations (UN) peacekeepers, had driven armed groups, including the Rwandan Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR), away from the larger mines in the eastern Kivu region, the DRC’s main conflict zone.

But this progress was not enough to satisfy US lawmakers. In July 2010 Congress approved the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act. This legislation’s section 1502 is aimed at companies that use so-called conflict minerals: gold, tin, tungsten or tantalum. It requires companies listed on the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to state if their products contain minerals from the Congo and if so, what steps have been taken to ensure that their sales do not fund armed groups. Some of these minerals are used in high-tech gadgets such as tablet computers and smartphones.

The International Crisis Group describes the Dodd-Frank act as a “qualitative leap forward” in that it makes due diligence, as applied to the supply chain for minerals, legally binding for the first time. So far, its achievements on the ground are questionable.

The UN’s independent “group of experts” on the DRC, which monitor the arms embargo, notes that an “unintended consequence” of the law has been “the withdrawal of reputable international companies from the DRC’s minerals market”. The United Kingdom-based International Tin Research Institute (ITRI) describes this as a “de facto embargo” of the Congo’s 3Ts, tin, tungsten and tantalum, caused by the reputational risk, particularly to high-tech end-users like Apple, Intel and Motorola.

The DRC’s export figures are debatable but observers agree they are sharply down for the 3Ts, although little changed for gold. One consultant for a western government puts the drop in 3T exports since 2010 at 60% to 80%, most of which he ascribes to Dodd-Frank.

Uwe Naeher, DRC project manager for Germany’s Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources (BGR), reckons the Congo’s exports of cassiterite (tin ore) have fallen from a monthly average of 1,300 tonnes in 2007–2008 to 350 tonnes in recent months, with tungsten and tantalum on the same trend. Prices paid to Congo’s artisanal miners of the 3Ts fell from $8 a kilo to less than $2 and have now recovered to $3 to $4. Globally, prices for the three minerals held up between 2008 and early 2012 despite the economic downturn.

How many hundreds of tonnes are smuggled and do not show up in any statistical ledgers? Rwanda’s exports have risen to 250 tonnes a month, whilst the DRC’s production cannot be more than 150 tonnes, Mr Naeher says. But Congo’s production of the 3Ts has fallen almost as much as exports, judging by the lack of activity in formerly thriving mining zones. “The effect of the embargo on the economy and livelihoods has been devastating,” he adds.

The hardship the law may be causing in some communities should only be temporary, says Senator Jim McDermott, who lobbied for section 1502 on the grounds that “the black market in minerals doesn’t have to fuel war and sexual violence”.

In September last year, the senator announced that in a year or so the DRC and its neighbours would be “close to their old level of production”.

A few sites in the DRC are now producing what Sen. McDermott describes as “cleanly bagged and tagged minerals”, or minerals traceable to a certified conflict-free mine. Until there is a viable traceability system, potential buyers cannot feel confident about satisfying Dodd-Frank requirements.

The Kivu region hosts about 2,000 mining sites. In a first phase, representatives of the DRC government, BGR, ITRI, USAID (the US government aid agency) and the UN peacekeepers (MONUSCO), are hoping to validate as conflict-free some 150 to 200 mines. That task is made even more challenging by the US State Department’s insistence that conflict-free must include free of extortion by the military.

Many of the 150 sites are three to four days from a passable road, making regular inspections difficult. Although 60 sites were inspected last year, BGR says that only one of the 3T mining sites can deliver to the required standards set by the region’s inter-governmental body.

And what of the effect of section 1502 on war and sexual violence? Sources within MONUSCO conclude that so far it has had little impact on the armed groups. The FDLR, the main focus of UN disarmament efforts, had lost control of nearly all the significant 3T sites in the DRC, and the routes to those sites, by late 2009.

The Congolese military has felt more of an impact because it controls most of the larger 3T sites. Cutting the links between the Congolese military and mining is an important long-term objective, but dislodging the army from the mines would increase insecurity, a MONUSCO member confided.

Dodd-Frank may have already heightened insecurity. The government withdrew army units from some of the mines, but other units replaced them, thereby fuelling tensions within the military, Mr Naeher says. Animosity between ex-rebel commanders integrated into the Congolese army and senior officers led to a mutiny by the former rebels in April. This has tipped North Kivu back into war. Miners without income or jobs, partly due to the US law, may have joined armed groups. A drastic reduction in money from mining must have strained relations between underpaid soldiers and local communities.

The SEC may announce its rules for implementing section 1502 later this year. It might make Congo’s minerals less toxic for buyers by dropping the current interpretation that conflict-free must include free of taxation by the military. Instead it could insist that a mine will not be validated if a military unit controlling a mine includes human rights abusers.

MONUSCO says it already refuses to include human rights abusers in its joint operations with the Congolese army. This condition would be more feasible than trying to prevent the Congolese military from profiting from mining sites.

Meanwhile, the mutiny in the Kivus continues. No one knows who controls the mines. But if the army’s control of the larger 3T mines is found to have been significantly reduced, the embargo may have more justification.

In the longer-term, section 1502 should help to raise revenue from the 3Ts. In addition, by formalising the sector, the law may encourage investment. Until then, the army will need to guard these mines even though military lawlessness remains part of the problem.