Show me the money

by Tolu Ogunlesi

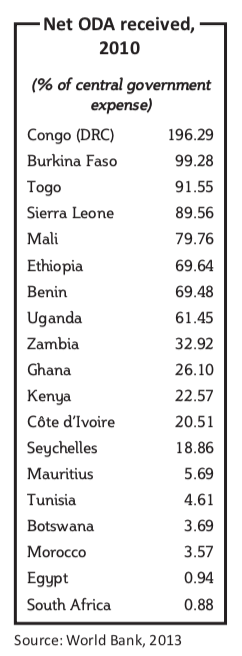

Every year billions of dollars in development aid stream into sub-Saharan Africa. Western countries and multilateral agencies like the World Bank and Britain’s Department for International Development (DfID) are the continent’s major donors.

Some countries in Africa depend on these grants and loans more than others. Overseas development dollars make up about 40% of landlocked Malawi’s annual budget. In contrast, oil-rich Nigeria’s foreign aid portion of annual spending is less than 6%, according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), a think-tank.

Africa has a dismal track record of transforming foreign aid into development: many African countries are poorer today than they were at independence. Of the 49 countries on the UN’s 2012 least-developed countries list, 33 were from sub-Saharan Africa. Only two African countries — Botswana and Cape Verde — of the 35 originally listed in 1971, have graduated from this designation. Clearly, something is wrong. Where have the hundreds of billions of aid dollars given to Africa gone?

This spectacular failure of foreign assistance has led to heated debate in recent years about the usefulness of aid, and strident calls for its overhaul. Among the more prominent voices is Zambian economist Dambisa Moyo, author of the 2009 polemic Dead Aid: Why Aid is Not Working and How There is A Better Way for Africa, a New York Times bestseller which was received with equal measures of acclaim and controversy.

Moyo classifies aid into three categories: “humanitarian or emergency” (triggered by wars and natural disasters), “charity-based” (from non-profits and foundations), and “systematic” (from richer countries and development financing institutions like the World Bank and DfID) — also known as official development assistance (ODA).

Systematic aid, in terms of size, dwarfs the other two kinds, Moyo argues. It often fails to achieve its goals: providing infrastructure, fighting poverty, disease, hunger and illiteracy, and building government skills. “Across the globe the recipients of aid are worse off; much worse off,” she wrote. “Aid has helped make the poor poorer, and growth slower.”

It is a radical argument to make, one echoed by British journalist Jonathan Foreman. The bulk of foreign aid is “’development aid’ intended not to help in emergencies, but to foster prosperity”, he wrote in a January 2013 article for the UK’s The Spectator magazine. But “after 60 years and $3 trillion of development aid, with one big push following another and wave after wave of theories and jargon, there is depressingly little evidence that official development aid has any significant benign effect on third-world poverty,” he wrote. It is “at best useless and at worst counterproductive”.

Equally disturbing is the selectiveness with which western donor countries engage with African countries, depending on what benefits are at stake. The West often turns a blind eye to corruption and gross human rights abuses in the countries they depend on for much-needed natural resources. They ply dictators and warlords with aid in exchange for access to everything from coltan to crude oil. However, when China does the same, signing unconditional oil-for-infrastructure deals with African autocrats, these western countries are the first to protest loudly.

In many cases, aid disbursement is tied to unrealistic conditions, which sometimes triggers the displeasure of the recipient country. In October 2011 David Cameron, Britain’s prime minister, threatened to cut aid to countries with anti-homosexuality legislation. This led Ugandan presidential aide John Nagenda to accuse the British government, in a BBC interview, of displaying a “bullying mentality”.

The World Bank, the IMF and celebrities such as Bob Geldof and Bono huddle at the other end of the aid debate. With them stand countless numbers of local and international non-profit and aid agencies, which rarely examine the effects of foreign assistance. These groups have created a business model for surviving on international grants, which they often manage to spend with minimal respect for transparency and accountability.

Some African governments recognise the importance of weaning themselves off their foreign aid fix. “True independence would come to Africa only when the continent boosts its internal trade and rids itself of its dependence on external aid,” Nigerian President Goodluck Jonathan said during a state visit to Botswana in September 2012.

With 162 million people, Nigeria has the largest population in Africa. This West African country is one of the world’s top 10 producers of crude oil, which generates 80% of the government’s annual revenues. Nigeria clearly does not need foreign aid. Yet in 2011 the country received $1.72 billion in development aid, according to the OECD. This represented less than 6% of Nigeria’s budget for that year and less than 2% of its total oil earnings.

“Nigeria has only a limited capacity to absorb aid effectively, partly because it has such a large oil income,” argued British economist Paul Collier in the chapter he contributed to The Debt Trap in Nigeria. The Nigerian government’s oil revenue “is a foreign resource inflow analytically equivalent to aid”.

Tighter spending controls and a lower tolerance for corruption would go a long way towards releasing the resources needed to fund development in Nigeria.

About 70% of Nigeria’s annual budget currently goes towards maintaining a bloated government bureaucracy, and a 2012 parliamentary probe revealed that fraudulent management of a petrol subsidy programme cost the country more than $6 billion between 2009 and 2011.

Unlike Nigeria, Malawi is a land-locked country of 15 million and was, until recently, resource poor. This south-eastern African country will continue to depend on foreign aid until it is able to harness its recent discovery of oil and gas in Lake Malawi. Donations from the US, Britain, the World Bank and the IMF make up about 40% of its budget. They delivered about $750 million in development assistance in 2011, on a budget roughly equivalent to $1.9 billion, according to the OECD.

Like Nigeria’s Jonathan, Joyce Banda, Malawi’s president, would like to end this foreign aid dependence. “We must move very quickly from aid to trade,” she told The Wall Street Journal in 2012. “We cannot sit here and lament and cry for foreign exchange that’s coming from donors, because then we have no control. It will come or it will not come. What we need to do is grow crops and export, manufacture and export.”

In general, this requires a careful and patient approach, but options do exist for some quick moves. Under the leadership of Banda’s predecessor, Bingu wa Mutharika, Malawi embarked on questionable spending ventures, like the 2009 purchase of a $22 million jet and dozens of Mercedes limousines. When she became president in April 2012, Banda promised to sell the aircraft and 60 of the limos. In January 2013 the government finally announced the opening of a bidding process for the airplane’s sale.

Until aid-dependent countries such as Malawi are able to stand on their own, the way forward is to find smarter ways of delivering and utilising aid in Africa. “We have learned that policies imposed from London or Washington will not work,” said James Wolfensohn, a former World Bank president, in March 2002. “Countries must be in charge of their own development. Policies must be locally owned and locally grown… We have learned that corruption, bad policies and weak governance will make aid ineffective.”

Eventually, the aim should be to ensure the radical “aid-free solution to development” proposed by Moyo. Western countries should scale down their protectionism — the “restrictive trade embargoes” that she says cost Africa up to $500 billion annually. Of course, African countries could and should do the same to promote trade amongst themselves. Another Moyo solution: bring banking services to the multitudes at the bottom of the economic ladder and encourage them to save.

Diaspora remittances to the continent are already a significant source of much-needed financing (see page 33). The World Bank estimates that diaspora remittances to sub-Saharan Africa amounted to about $30 billion in 2012. Nigeria alone accounts for two-thirds of this sum.

Providing support to the private sector — such as the removal of bureaucratic bottlenecks and improving access to cheap funding — is equally critical. Useful as foreign aid is, says Charles Robertson, an economist at Renaissance Capital, a Russian investment bank, “it won’t invigorate the private sector on its own. That depends on African entrepreneurs.