Book review

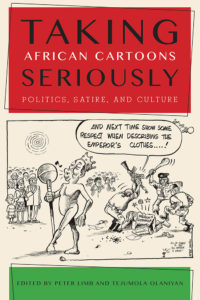

Taking African Cartoons Seriously: Politics, Satire, and Culture

Edited by Peter Limb and Tejumola Olaniyan,

Michigan State University Press | East Lansing; 2018

Aristotle noted that man was a social animal, but also that we are the only species that laughs. What we laugh at remains something of a mystery.

We humans also practise professions that make of laughter a source of livelihood: court jesters have been around since the time of the pharaohs, but now we also have professional comedians and cartoonists – as well as those unwitting comedians, politicians. Cartoons, which often ridicule this latter species, are by definition funny. This is all the more reason why we should be Taking Africa’s Cartoons Seriously, as the authors of this book argue.

The flourishing of Africa’s cartoonists indicates that democracy is taking root. Edited by Peter Limb and Tejumola Olaniyan, the book is meant to correct the lack of analysis of political cartoons, and to introduce new approaches to the phenomenon. It contains an introduction and overview, seven essays, and five interviews with prominent cartoonists from sub-Saharan Africa.

The flourishing of Africa’s cartoonists indicates that democracy is taking root. Edited by Peter Limb and Tejumola Olaniyan, the book is meant to correct the lack of analysis of political cartoons, and to introduce new approaches to the phenomenon. It contains an introduction and overview, seven essays, and five interviews with prominent cartoonists from sub-Saharan Africa.

The works analysed are by practitioners in Kenya, South Africa, Nigeria, and Ghana, while those interviewed are from Botswana, Namibia, Nigeria, Kenya and South Africa. Most of the essays present analyses of how and why cartoons work, while two present the vagaries of media freedom in South Africa and Ghana.

It is instructive that the cartoonists’ countries of origin influence their works and their thoughts about what they do. The political regimes in power in each case determine the form and content. Democracy is a necessary condition for cartooning that does not descend into hagiography.

Nigeria, the most populous country on the continent, has a long history of military rule and sporadic attempts at democracy. Ganiyu A Jimoh’s examination of cartoons about the Nigerian police uses semiotics as a methodology to demonstrate how cartoons work. He also provides a brief history of corruption in the police force before turning to cartoonists’ use of physical features: the potbelly – to denote corruption and ill-gotten wealth, as well as indolence and a dereliction of duty.

Caricature is a favourite device of most cartoonists, exaggerating the physical features of leaders and the elites – a nose enlarged, a look in the eye made hyperbole, a character trait rendered hilarious. Caricature diminishes the authority of the powermonger, stripping him (more often a him) of legitimacy and reducing him to less than ordinary.

Olaniyan examines the work of Bisi Ogunbadejo, a veteran cartoonist who focuses not on political failure but on “how such failures come to be” because of the human condition. His work, says Olaniyan, exemplifies the cartoon of exploration rather than the more common cartoon of display, where ridicule is paramount. While Ogunbadejo’s exploratory cartoons do not produce belly laughs, they present “irresistible humour at its most troubling unhumorous best”, plunging the reader into contemplation of a paradox.

Baba G Jallow explores the decade after 1957 in Ghana, during the reign of Kwame Nkrumah, the first president of independent Ghana. Nkrumah went from being the nation’s saviour to declaring a one-party state, crowning himself president-for-life and encouraging his people to see him as a god.

Cartoonists showered him with praise, but the day he was deposed, the very same cartoonists ridiculed him and celebrated his downfall. Jallow argues, unconvincingly, that excessive praise can be a coded form of critique. “What appears to be caricatures of one person or issue might actually be caricatures of those who caricature the person or issue,” he argues. It seems he fails to see that not all cartoons achieve their aim. Some simply aren’t much of anything: neither funny, nor acute, critical nor interesting.

Joseph Oduro-Frimpong examines a later period in Ghana, the fourth republic of 1993, after which “Ghana boasts a robust press freedom”. He focuses on The Black Narrator, “the first to exemplify the changing nature of cartooning in Ghana since 1992”. This cartoonist tackles corruption in government, the judiciary and sanitation – the latter an issue that posed a grave threat to public health. Oduro-Frimpong is concerned to break the distinction between entertainment and political resistance, seeing cartoons as “one of the myriad ways ordinary people cope with and undermine the politics of hegemony pursued by the political elite”.

Seeing cartoons as a “running commentary on events”, Gathara sets out a brief history of the media and cartooning in Kenya, paying homage to pioneers such as Paul “Madd” Kelemba, “the first indigenous political cartoonist to reach national prominence” who emerged in 1986. Madd was succeeded by Godfrey Mwampembwa, aka Gado, now one of the foremost cartoonists on the continent.

These days, the state sometimes uses the threat of litigation to silence critics, and in 2014 the editors of The Standard, a Kenyan news outlet, were summoned to State House in connection with an exposé about state overspending. Gado was the victim in April 2015, asked by his editor to “take a break” before being sacked in February 2016. As a consequence, says Gathara, self-censorship has become the greatest threat to media freedom in Kenya. But the state is not the only threat: advertisers also play a nefarious role in keeping certain issues out of newspapers.

Paula Callus explores tactics of subversion in her chapter on animation, a form allied to cartooning but requiring technological devices rather than two-dimensional paper. She points to the increasing ubiquity of the Internet, smartphones and new forms of production and distribution for cartoonists, filmmakers and media practitioners. She focuses particularly on emerging animators – such as Gatumia Gatumia, whose The Greedy Lords of the Jungle, a short animated film that could be interpreted in myriad ways, is a critique of colonialism but also of power relations in post-colonial Africa.

The producers of these animations rely on the moving image as a way of bypassing the eye of the censor to get to children, thereby producing sublimated critiques of power relations. But she cautions that rather than simply being oppositional, some of these artists are prone to imbrication in the systems they question, sometimes becoming complicit with the aims of funders, or of government’s desire to develop the IT sector.

South Africa looms large in the book. It has unique features, most notably a history of oppressive relations between white overlords and black subjects, a condition that has not been entirely eradicated by more than two decades of democracy. The country’s early cartoonists – mainly white, exploiting the space made possible by a whites-only democracy – appear to have long experience of how to cock a snook at power, a tradition continued by Jonathan Shapiro, aka Zapiro, one of the most respected practitioners in Africa.

Post 1994, the ruling African National Congress (ANC) has been angered by Zapiro’s disillusionment with the failure of the post-apartheid project, especially when he portrayed younger leaders as monkeys, devolving rather than evolving, betraying the traditions set by Nelson Mandela. Indeed, Zapiro has laid himself open to charges of racism, which the ANC has exploited.

A new mood swept the country during the reign of Jacob Zuma, when democracy waned, corruption became a structural feature of the economy, service delivery plummeted, and a new smartphone-carrying generation began to agitate against the inequalities that weighed on them. Andy Mason and Su Opperman, in both their interview with Zapiro and their history of the media after apartheid, foreground quite radical shifts in relations between cartoonists, the public and the powers that be. They present a history of debacles: rude depictions of Zuma caused outrage among ANC leaders and supporters – more so if white artists produced these, as they were more prone to charges of racism.

Mason and Opperman’s interview with Zapiro seems overly concerned with the cartoonist’s disengagement from a new public, lamenting the reactions of young black people who, they imply, should know that Zapiro is a struggle veteran. One can’t help thinking these writers are failing to come to terms with a new set of struggles inspired by new conditions. But they raise the question of self-censorship: should Zapiro watch what he says lest he offend a new generation? The issue has taken on a new urgency in the wake of the Charlie Hebdo murders in Paris and the awful dialectic between Islamic terrorism and Islamophobia. Cartoonists have to court outrage as well as take a side, and sometimes are able to convey the difficulty of treading this fine line. Effective cartoonists use irony to overcome this duality, but this is not always welcome.

The book raises a series of questions, the central one being what cartooning is meant to do: should it reflect, enlighten, or castigate? All of the above? For Aristotle, comedy was the representation of people “worse than us”, and what we laugh at is the ugly and the shameful. He was right!

[author] [author_image timthumb=’on’]https://digitalmallblobstorage.blob.core.windows.net/wp-content/2018/01/AiF-44-Momoniat-2.jpg[/author_image] [author_info]YUNUS MOMONIAT is a researcher and writer at South African History Online and an occasional political commentator.[/author_info] [/author]