Central Africa: Lord’s Resistance Army

Attacks by the violent and mystical group may be diminishing, but fear of its resurgence remains high

There has never been a better time for the world to tackle the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA). Attacks by Joseph Kony’s feared rebel group have dwindled significantly in the past two years, and deserters tell of low morale among his fighters – which could present the greatest opportunity yet for regional actors to quash the 27-year-old movement. But Mr Kony has a terrible penchant for survival, and many fear that unless regional and international actors honour their commitments to quell the Ugandan rebels, this could be merely a lull before another violent LRA storm.

“The Lord’s Resistance Army is likely weaker than it has been for at least 20 years,” said Michael Poffenberger, executive director of The Resolve, a US-based advocacy group. “LRA groups are scattered across an area in central Africa the size of California and morale among the Ugandan combatants that comprise the core of its forces is at a new low.”

The LRA committed 54% fewer attacks in the first half of 2013 compared to the same period in 2012, according to statistics collected by Invisible Children, a US-based advocacy group. The organisation’s data is based on a high-frequency early-warning radio system that allows villagers in LRA-affected areas to keep track of the rebels’ activities and warn one another about their movements.

The LRA crisis tracker, an online service created by The Resolve and Invisible Children, shows a dramatic drop in LRA activity in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), with a decrease of 98% in LRA killings in 2012 compared to 2009 (from 1,098 to 22). “In Uele, north-eastern Congo, many fighters confess to being hungry and even the core fighters, mainly from Uganda, have little desire to fight,” writes Central Africa analyst Thibaud Lesuer, writing for the International Crisis Group (ICG), a Brussels-based think-tank.

The LRA originated in northern Uganda in 1986, ostensibly to topple the government of President Yoweri Museveni. While Mr Kony claims that the LRA is a faith-based movement, the group has been reduced to banditry with a vicious history of killings, mutilations and abductions. LRA fighters have killed more than 100,000 people in the region over the past 25 years, according to a statement from UN General Secretary Ban Ki-moon in May 2013. The LRA has abducted at least 25,000 children, who have become fighters and porters, according to Human Rights Watch. The LRA’s campaign has displaced millions across the region.

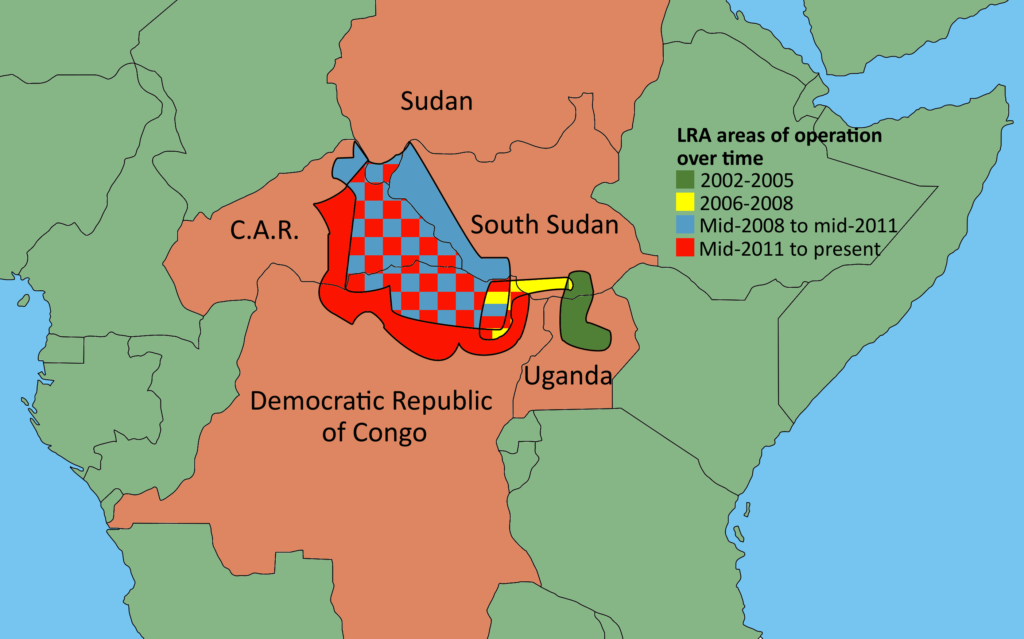

A series of operations by the Ugandan army, starting in the 1990s, succeeded in largely pushing the LRA out of the country by 2006. The LRA then fragmented into several highly mobile groups operating across the DRC, the Central African Republic (CAR) and, to a lesser extent, South Sudan, according to a 2011 UN report. Based on interviews with deserters, The Resolve believes Kony himself could be hiding in two places: either in the Sudanese-controlled enclave of Kafia Kingi, a disputed territory along the border of Sudan and South Sudan, where the LRA is thought to have bases; or else in the northern CAR.

Source: UN Conciliation Resources; Invisible Children; The Resolve

The decreased number of attacks in the past two years correlates with what is believed to be a sharp decrease in the number of fighters still loyal to the LRA. An already depleted fighting force of 400 in June 2010 is now down to roughly 250 fighters, according to a 2013 Resolve report.

A recently renewed military effort may assist in ending the group’s infamous activities once and for all. Joint Uganda-African Union (AU) operations against the LRA resumed in October after a six-month lull during which civil strife in the Central Africa Republic curbed their efforts. Uganda, which is leading the operations, ordered foreign troops out of the CAR in April after the Seleka rebel coalition toppled the government of François Bozizé. “But now we have the green light to resume and are making progress,” said Ugandan army spokesman Colonel Paddy Ankunda.

In March 2012, the AU and UN initiated a joint Regional Task Force to hunt the LRA rebels with 3,500 troops from the CAR, DRC, South Sudan and Uganda, according to a June 2013 African Union report. For the first time in two years, Mr Poffenberger says, the joint task force is operating in all three regions outside Uganda – CAR, DRC and South Sudan. Previously the AU had failed to engage forces from CAR and DRC.

The US government is supporting the Ugandan forces. In October 2013, the US Congress agreed to provide $35m in logistical support toassist with tracking LRA radio signals, transport and other non-combative assistance to regional efforts to end LRA violence. This is in line with pledges President Barack Obama made in 2009 when he signedinto law the Lord’s Resistance ArmyDisarmament and Northern Uganda Recovery Act.The US sent a hundred of its elite Special Operations troops to CAR in 2012 to offer hands-on assistance to the combined effort, according to The New York Times.

And it seems to be working. Areas with a Ugandan army presence coupled with logistical support from the US government and private military contractors have witnessed a decrease in large-scale LRA attacks, according to Invisible Children. The majority of mass LRA attacks, defined as killing five or more people and/or abducting ten or more people, occurred from January 2012 to June 2013 in the CAR areas that are not under the influence of the Ugandan army, the Ugandan People’s Defence Force (UPDF). The LRA abducted nearly triple the number of people per attack in areas outside of the US-UPDF’s influence, an Invisible Children brief said.

The crucial support that the Sudanese government has historically afforded to the LRA appears to be waning. For decades Khartoum supported the LRA in South Sudan as a proxy force to counter Uganda’s support to Sudan’s former enemies, the Sudan People’s Liberation Army.

Sudanese authorities expressed their commitment in October 2012 to support the AU operation against the LRA after a meeting with the AU’s special envoy for counter-terrorism, Francisco Madeira. Such pledges are a marked change from the past when Khartoum played an instrumental role in feeding, arming and defending LRA ranks. Uganda’s 2002 “Operation Iron Fist” against the LRA, for instance, was thwarted after Khartoum prevented Ugandan forces from pursuing Mr Kony past a certain demarcated line.

While The Resolve has reported that the LRA had a camp in Sudan-controlled territory in late 2012, Mr Poffenberger suspects that Mr Kony is no longer receiving direct government support. Support from individual members of Sudan’s army may still assist LRA fighters in terms of mutually beneficial trading, but Mr Poffenberger said it was “nothing on the scale of what Khartoum used to do”.

The LRA are now split into fractious groups with limited communication and logistical support, Mr Poffenberger said. Morale among wary LRA ranks is understandably low, he added. Cognisant that his pursuers can track the LRA through their radio signals, Mr Kony curtailed most radio communication, forcing many rebel commanders to remain isolated without clear direction for long periods of time. “A growing mistrust of Kony’s promises of taking Uganda are taking its toll,” Mr Poffenberger said. “Out of two dozen defectors we spoke to recently, all of them talk about low morale within the ranks.”

LRA forces in the Congo are reaching out to civilians, according to an analysis by Invisible Children. This year, nine letters—written by LRA fighters to local communities in northern Congo and intercepted by Invisible Children’s LRA tracking system—have expressed the writers’ desires to leave the movement; in some cases requesting assistance by civilian communities to do so.

But the LRA has time and again demonstrated its capacity to go underground for a time and then surge again, often more violent than before. Mr Kony’s brutal tactics of abducting and manipulating children—coupled with terrible punishments for attempted desertion—have proven a successful, if tragic, cocktail ensuring the movement’s longevity.

“I was forced to kill one of my neighbours with a rake,” said Angela, a 10-year old former LRA fighter in South Sudan who managed to escape in 2006 and sought rehabilitation at the Toto-Chan Centre in the country’s capital, Juba. Fearing retribution from her village for her deeds while equally fearing her LRA captors, Angela felt trapped and remained with the rebels for eight months before escaping. Former journalist Frank Nyakairu, who covered the LRA for 10 years,explained that many LRA fighters, abducted as children, have developed incredible survival skills in the bush environment.

To ensure that such a resilient force is defeated, regional and international actors must be fully committed. Unfortunately, none of the players has until now demonstrated the necessary sustained dedication. Mr Poffenberger says that some of the regional governments have even become obstructionist. “The [DRC] government has denied the LRA are a problem,” he says.

Since the LRA thrive in remote, marginalised communities in the DRC, the DRC government as well as UN peacekeepers are more focused on other rebel movements fighting in the Kivu region. Additionally, given Uganda’s past interferences in Congolese affairs, the government is understandably wary of any Ugandan presence in their territories. “The military pressure on the LRA in [the] DRC is close to zero,” the ICG’s Mr Lesuer said. “Congolese and MONUSCO forces secure the main roads but do not exert any tactical pressure on the LRA.”

Funding constraints linked to economic pressures could also play a role in weakening the fight against the LRA. Since the beginning of 2013, 11 of the 19 international nongovernmental organisations focusing on LRA issues have withdrawn because of funding constraints, according to the latest Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs report, which was released onOctober 9th 2013.

A decrease in attacks and visibility does not necessarily indicate a dissipated rebel movement, however. Mr Kony may lay low for now, knowing that recent regional and international pressures are short-lived. Based on interviews with deserters, The Resolve believes that Mr Kony could be ordering commanders to refrain from large-scale killings, and to conduct attacks purely for survival and looting purposes to deflect international attention from the LRA and, consequently, future funding to pursue him.

The reduction in major abductions and killings in favour of small-scale looting also makes it difficult to distinguish the LRA raids from those of other bandits, Invisible Children reported in its mid-year report. Insecurity caused by the proliferation of armed groups in eastern CAR, for instance, has allowed the LRA to exploit vast stretches of ungoverned territory where monitoring and identifying its presence is generally untenable.

Limited attacks on civilians may simply mean that the LRA are targeting other residents in the region—endangered elephants. The LRA has poached ivory in the DRC and the CAR since arriving there in 2005 and 2006, which coincides with the gradual reduction of LRA attacks, according to a joint June 2013 report bythe Enough Project, The Resolve, Invisible Children, and the Satellite Sentinel Project, a US-based monitoring group.

In October 2012, LRA commanders delivered 38 elephant tusks to Mr Kony in the Kafia Kingi enclave, The Resolve reported. According to international activism and advocacy group Animal Rights Action, the worldwide trade in illegal ivory is worth about $1bn annually.

Nevertheless, all the evidence suggests that Mr Kony has never been weaker. The challenge now is to ensure that the commitment of regional and international actors is maintained until LRA is defeated completely. In a remote environment where the concerns over impoverished, voiceless citizens are limited, however, this will take the kind of political will that until now has been lacking. With a plethora of security issues in the region, the promising joint regional effort to defeat the LRA could be short-lived. If that happens, it is the ordinary residents of the CAR, the DRC and, to a lesser extent, South Sudan – who over the past seven years have become all-too-accustomed to the LRA terror – who will be the on-going victims.

Sister Angélique Nako Namaika won the 2013 UNHCR Nansen Refugee Award for her work helping LRA victims in Dungu, northern Congo. “Outside of Dungu, there are still incidences of LRA,” she said. “People are still scared to go back home even if there are less attacks – the LRA still exist and [this] still contributes to the waiting. They are waiting for the day when it is completely safe.”

[author] [author_image timthumb=’on’][/author_image] [author_info]Tom Rhodes, based in Nairobi, is a freelance journalist and consultant for the Committee to Protect Journalists, a New York-based media advocacy organisation. Tom has worked as a teacher at a university in Khartoum and helped initiate southern Sudan’s first independent newspaper, The Juba Post, in 2004.[/author_info] [/author]