Central African Republic: the rebels formerly known as Seleka

This coalition has taken over the country and plunged it into unmitigated violence and chaos

Seleka may be the worst tyrant to ever have terrorised the Central African Republic (CAR).

This is not said lightly. Whatever can go wrong in the CAR usually does. The country is often referred to as a failed state. Sometimes it is referred to as a non-state surrounded by other countries. More often than not it is simply forgotten.

Perhaps the only good Seleka has done is to briefly attract international attention to a crisis that has been smouldering for decades, a catastrophe Seleka has succeeded in exacerbating in a very short time. Looting, pillaging, rape and murder have been synonymous with Seleka since the rebel group launched its first offensives in December 2012.

Seleka means “the alliance”in Sango, the local language. In August 2012 three separate rebel groups joined forces – the Union of Democratic Forces for Unity (UFDR), led by the man who is now the CAR’s self-proclaimed president, Michel Djotodia; the Convention of Patriots for Justice and Peace (CPJP), led by the man many believe is the real power behind the throne, Nourredine Adam; and the Patriotic Convention for the Salvation of Kodro (CPSK), led by Mohamed-Moussa Dhaffane. A large number of their followers come from the country’s north-east, notably the district of Vakaga. This is a dry area wedged between Chad and Sudan’s Darfur region, where most of the local population is Muslim and Arabic-speaking, in contrast to the Christian/animist and Sango/French-speaking south and west.

Messrs Djotodia and Adam boosted the strength of their forces by recruiting hundreds of Chadians and Sudanese. This was an easy task for both rebel leaders given the strong cultural, linguistic, religious, political and military links they share with their neighbours. During the early years of the Bozizé administration, Mr Djotodia wasthe CAR’s consul to Nyala, the capital of South Darfur. Mr Adam has strong family links in Chad, as well as owning several businesses in Chad’s capital, N’Djamena.

Over the past two decades, the factions forming Seleka have fought each other for dominance in various parts of the hinterland in a slow-burning bush war, a state of affairs that has marked much of the CAR since independence from France in 1960. Just about the only tie binding Seleka together was the common cause of removing François Bozizé from power.

Mr Bozizé, a former security chief for the infamous self-proclaimed emperor of the Central African Republic, Jean-Bedel Bokassa in the 1970s, made several unsuccessful attempts before ultimately coming to power in a military coup in 2003, toppling then-president Ange-Félix Patassé.

Over the past decade, Bozizé-controlled armed forces (les Forces Armées Centrafricaines, FACA), have repeatedly attacked the capital of Vakaga district, Birao, while thousands of terrified residents hid in the bush and survived on whatever they could scrape from the land. Just about the only central government presence there while Mr Bozizé was in power was a FACA garrison near Birao, which spent much of its time burning towns, villages and crops. The locals believe they were targeted because they did not support the president at election time. It was not surprising to see an anti-Bozizé coalition form there because of this abuse.

The alliance started with about 5,000 members, but quickly grew to about 25,000, swollen with an influx of rebel fighters from Chad and Sudan. This was not a reflection of Seleka’s support, but rather the result of the close links forged by Messrs Djotodia and Adam with the leadership in N’Djamena and Khartoum. One of Mr Djotodia’s closest allies, Sudanese general Moussa Assimeh, had been a leader of the janjaweed, the notorious mounted rebel group supported by Khartoum which led the terror campaign in Darfur. (Mr Djotodia fired Mr Assimeh in mid-October in an unsuccessful attempt to prove that he controls Seleka, although his influence is still believed to be significant.)

Once the rebels had installed themselves in Bangui, the capital, Mr Djotodia named former human rights lawyer Nicolas Tiangaye prime minister in an attempt to put a more acceptable and inclusive face on Seleka. Mr Tiangaye had acted briefly as prime minister earlier this year in a short-lived government of national unity under Mr Bozizé. That partnership ended when Seleka decided to march on Bangui in March. Early hopes that Mr Tiangaye might be a stabilising influence on the movement evaporated months ago.

Despite Mr Djotodia’s denials, extensive proof exists that a large percentage of Seleka membership is not from the CAR. Arabic is the lingua franca of Seleka, a language spoken only by a small minority in the northeast. Linguistic differences contribute to the perception that Seleka is a foreign invading force.

Most Central Africans believe Seleka and its violent chaos serve the interests of Chadian president Idriss Déby. Although he officially denies supporting the rebels, Mr Déby has always played a prominent role in the politics of his southern neighbour. Ten years ago he helped Mr Bozizé topple Mr Patassé and then propped him up with soldiers for his presidential guard.

Mr Déby’s soldiers also form the biggest part of the regional stabilisation force in the CAR, the Multinational Force of Central Africa (FOMAC), which is converting into an expanded African Union force and which may be transformed into a UN peacekeeping operation. When Seleka began its rapid advance towards Bangui in March 2013, FOMAC forces stepped aside and let them reach the capital virtually unhindered, apart from skirmishes, which led to the deaths of 15South African soldiers who had been sent to bolster Mr Bozizé.

Mr Déby has reasons to fear a stable CAR. He has his own troubles in southern Chad, where he is unpopular. His administration draws most of its wealth from southern Chad, an oil-producing region that straddles the border. Oil is not coming out of the ground on the CAR side—Seleka and Chadian rebels have kept up a reign of terror to keep that from happening. Peace on the border area would mean Chad would have to share its black gold.

As for the Sudanese, President Omar Al-Bashir faces increasing domestic strife at home, the loss of oil revenue since South Sudan gained independence as well as an International Criminal Court arrest warrant hanging over his head. The CAR, through a Seleka proxy, could potentially offer Khartoum a new revenue stream through oil, diamonds, gold, uranium, timber as well as an opportunity to expand Muslim influence in the region.

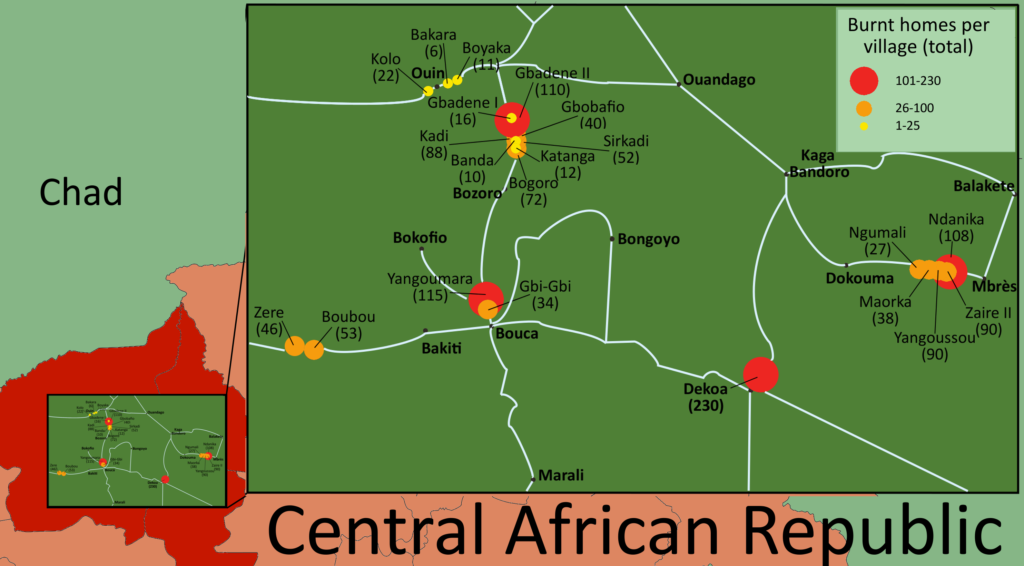

Mr Djotodia claims that most of Seleka’s operations against civilians are an attempt to control pockets of territory regarded as Mr Bozizé’s stronghold. But a religious element to the violence is increasingly obvious: pitting a mainly Muslim Seleka against the predominantly Christian and animist majority. Former government officials are circulating rumours in Bangui that Qatar is funding Seleka, fuelling fears that the CAR is a new target for Islamic extremist groups operating in West and East Africa. Increased sectarian violence in the north-west and the south-east helped prompt France last October to decide to increase its military presence in the country from 410 to up to 750 troops by the end of the year. Terms of the expanded deployment have yet to be decided.

Religion does not bind Seleka. Nothing does. Cracks appeared in the alliance before the rebels even reached Bangui. Mr Djotodia has never been able to control his alleged followers. Human Rights Watch and the Worldwide Human Rights Movement have documented Seleka atrocities since the first rebel attacks in December 2012.

Not long after seizing power, the Djotodia administration arrested one of Seleka’s original founders, CPSK leader Mohamed Dhaffane, and threw him into prison.Regional analysts saw the move as an attempt to convince an increasingly sceptical international community that discipline within the ranks was being taken seriously. Mr Djotodia blamed Mr Dhaffane for attacking civilians. Since his arrest in June 2013, however, assaults against non-combatants have increased.

In September, faced with reports of rising incidents of violence, including more than a hundred deaths in fighting between Seleka rebels and locals in the Bossangoa area north of Bangui, Mr Djotodia announced the dissolution of Seleka. Like other pronouncements, this has done nothing to stop the terror campaign waged by the rebels formerly known as Seleka.

History has a habit of repeating itself in the CAR. This author has no doubt that the vast majority of people despise the Djotodia administration and Seleka. Although few politicians, if any, have enjoyed widespread support at any point since the country’s independence, there has never been such universal condemnation of the people in power as exists today.

The chaos and terror is not sustainable. It is probably only a matter of time before the Seleka chapter in CAR’s history is referred to in the past tense. Whatever replaces it is not likely to provide the panacea the Central Africa Republic has desperately needed for decades. Even a return to the situation prior to the arrival of Seleka in Bangui would be an improvement. Ideally, the international community should consider establishing a transitional period of administrative guardianship.

[author] [author_image timthumb=’on’][/author_image] [author_info]David Smith is the director of Okapi Consulting based in Johannesburg. He has set up radio services in conflict and post-conflict zones including the DRC, the Central African Republic, Chad and Somalia. David has also worked extensively with the UN on media projects.[/author_info] [/author]