Tunisia’s telecommunications troubles

The infrastructure exists but is not exploited

by Anne Wolf

Tunisia claims to have one of the highest internet and mobile phone penetration rates in North Africa. Its communications ministry website boasts that the country is “a favourable site for the growth of ICT [information and communications technology] firms, both locally and globally”. Its “improved infrastructure” is a key driver behind this status.

Yet this rhetoric conceals the controls that the Tunisian government places on the use of high-speed internet, more restrictive than most other countries in the region. In Algeria the government limits internet access as a way of controlling the population. In post-revolutionary Tunisia, mismanagement and vested interests also constrain its citizens’ access to landlines. Their bills for international phone calls are amongst the highest in the world.

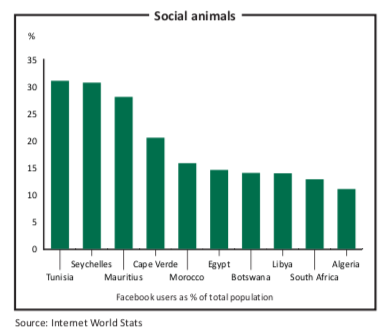

How can this paradox be understood? Tunisia gained a reputation as an ICT leader because of the important role social media played in the ousting of former President Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali on January 14th 2011. With an internet penetration rate of 41.4% in 2012, Tunisians are among the world’s most active consumers of Twitter and Facebook, according to Internet World Stats, a website that tracks social media usage. Tunisia had 3.3m Facebook subscribers on December 31st 2012, equivalent to a penetration rate of 31%, the highest in Africa.

Moreover, Tunisians own many mobile phones, which also played a role in the 2011 revolution. The International Telecommunication Union (ITU) estimates that the country’s cell phone penetration rate is 120%, which means that the number of active mobile phones in Tunisia exceeds the country’s population of 10.8m.

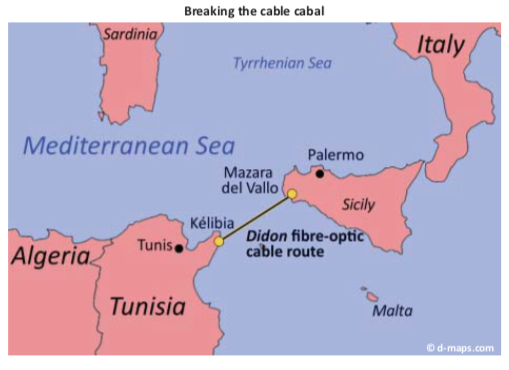

Tunisia’s internationalinfrastructure is also fairly modern. The country can pride itself on two ground connections to Libya and Algeria and three undersea cables to Europe ensuring good international phone connectivity. “This also means that, in principle, Tunisians could benefit from global [competitive] prices,” explained Antonio Nucifora, the World Bank’s lead economist for Tunisia, in an interview with Africa in Fact.

But Tunisia’s foremost telecommunications provider, Tunisie Télécom, has a monopoly over this infrastructure, fixing the costs of international calls at around 40 cents per minute, which is comparable to the high prices paid in Myanmar and the Republic of Congo, where poor governance and undeveloped infrastructure have held back the broadband market.

These high costs keep most Tunisians from calling their relatives and friends abroad. The average Tunisian spent only about 25 minutes per year on overseas calls in 2010, far below the regional average of 181 minutes, according to a June 2012 World Bank report. Moreover, while international phone calling in North Africa jumped a cumulative average of 10% between 2004 and 2010, in Tunisia it increased only 1%. The high charges have led many Tunisians to use Skype to make free international phone calls, but the quality is poor and disruptions are frequent.

These expensive call rates “strongly limit Tunisia’s integration into the international economy”, Mr Nucifora said. In an effort to promote foreign investment, Tunisia claims that a foreign company can

launch satellite operations in Tunisia at half the cost of a competing Eastern European country. This is not enough, however, to make Tunisia attractive. “For a country trying to be at the forefront of offshoring, Tunisia ought to have much more competitive telecommunications services,” he added.

Aside from its monopoly over international calls, Tunisie Télécom owns 96% of the country’s fixed broadband lines. “Only the elite can afford an ADSL connection,” explained Ali Babbou, president of Global Net, a Tunisie Télécom partner. Even if the company dropped prices, a few more customers might subscribe, but not enough to balance the losses. “Economic pressure does not make it profitable for Tunisie Télécom to target more consumers by dropping prices,” he explained.

Since the 2011 Arab spring, Tunisia’s economy has suffered heavy losses. Political instability and insecurity have led to a sharp drop in the country’s economic outlook. With two political assassinations within the past eight months, the situation is unlikely to improve any time soon. High unemployment, which many consider one of the principal reasons for the uprising two years ago, is now even higher at 16% (over 30% among university graduates) compared to 13.3% in 2010, according to Tunisia’s national statistics agency.

The digital divide separating the coast’s urban areas from the interior’s countryside is another stumbling block for the country’s phone networks. Tunisie Télécom’s lines reach mainly Tunisia’s northern capital and the Mediterranean seaboard, where most business is clustered and two-thirds of the population lives. Tunisia’s less populated rural centre and south-west are the country’s most fragile economic regions. They have little chance of catching up, however, because of their limited access to fixed telephone lines and high-speed internet.

The countryside relies almost ex- clusively on third generation (3G) internet access through mobile phone networks. Since two mobile phone service providers, Orange and Tunisiana, were allowed to compete with Tunisie Télécom (in 2002 and 2010 respectively), prices have dropped but coverage in rural areas remains patchy. However, “the future of telecommunications still lies in ultra-fast cable connections,” Mr Nucifora insisted. “If Tunisia wants to

become an ICT hub more consumers must have access to this infrastructure.” Ironically, Tunisia is equipped with a rich variety of alternative infrastructure that could be exploited to reach rural regions. For example, the Tunisian Society for Electricity and Gas and its national railway both have fibre-optic cables that reach many interior zones and could be used for telecommunications transmissions. Alternative infrastructure is already widely used in Morocco, making the country much more competitive than Tunisia.

The Tunisian government has done little, however, to create an environment that encourages the use of this existing infrastructure and Tunisie Télécom’s administration is feeble. “The problem is that Tunisie Télécom is largely leaderless,” Mr Babbou said. “Its management has changed several times since the revolution.”

In June 2013 Emirates International Telecommunications confirmed it would sell its 35% interest in Tunisie Télécom. The possibility that its highly qualified senior staff might leave the country aggravated the leadership crisis.

Members of the Ben Ali-Trabelsi clan, the quasi-mafia of the former president and his wife, Leila Trabelsi, once managed Tunisie Télécom. Shortly after their hasty departure, Tunisie Télécom’s powerful labour union organised a series of protests accusing the company of corruption and nepotism at the highest levels. To placate the union, management cut the salaries of most senior employees.

Tunisians, however, remain sceptical of the company’s leaders and senior staff. Many blamed Tunisie Télécom when thousands of text messages were sent to supporters of the ruling Islamist party, calling upon them to join pro-government demonstrations last July. Although a private operator was later found to be responsible for distributing the messages, the incident illustrates the extent to which the populace still mistrusts the country’s telecommunications giant.

Tunisie Télécom’s 35% ownership of the Tunisian Internet Agency (ATI) reinforces these suspicions. The ATI manages national internet traffic and was created in 1996 to censor and control. Although this function ceased after the revolution, in theory, the ATI still has the means to filter and censor internet content.

A court ordered ATI on May 26th 2011 to block porn sites, claiming that they are a threat to Muslim values and minors. This decision reminded many Tunisians and international observers of the enduring thin line between censorship and internet freedom. Reporters Without Borders, a freedom of expression watchdog, warned that “old practices [may] resurface”, and condemned “any court decision that would restore the filtering practices”.

To respond to this foreign and mounting domestic criticism, Tunisia’s National Constituent Assembly amended Tunisia’s communications law last April and strength- ened the regulatory powers of the National Telecommunications Commission (INT) to guarantee that its decisions are implemented even if an operator appeals to a court.

Significantly, the INT formally approved the use of the fibre-optic cables owned by the railway and the electricity and gas companies on June 28th. Concrete steps have not been taken yet to use this promising infrastructure.

Last May Tunisiana and Orange announced a partnership agreement with Interoute, a UK-based telecommunications company, to extend a 170km fibre-optic cable from Sicily to Tunisia. In the long term, this might force Tunisie Télécom to lower its exorbitant calling charges. On the other hand, this development illustrates the enduring dichotomy of Tunisia’s telecommunications industry: the inability to take advantage of the existing infrastructure, rather than its absence. Until this disconnect is resolved, the inclusive social and economic goals of the Tunisian revolution will remain on hold.