Africa’s monetary unions

Plans to launch a common currency in West Africa flounder

With the structural failings of the European monetary union at the root of Europe’s economic malaise, the viability of a single monetary union in west Africa has come squarely under the microscope.

Fifteen states in this African bulge formed a regional economic union in 1975 known as the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) to promote growth, stability and economic development. Languages and currency, however, divide the regional grouping.

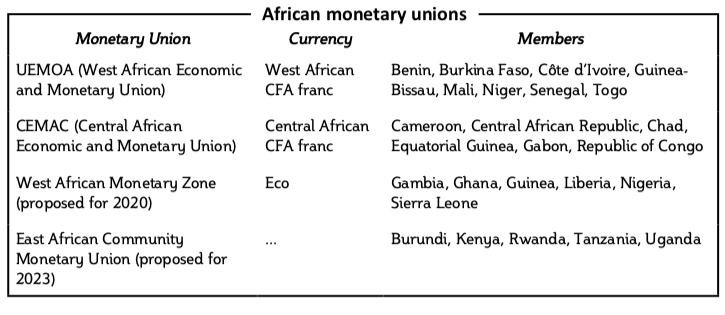

ECOWAS’s seven former French colonies use the CFA (for Communauté Financière Africaine) franc as their common currency. These French-speaking nations—Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Mali, Niger, Senegal and Togo—together form the West African Economic and Monetary Union (or UEMOA after its French initials), a customs and currency union established alongside ECOWAS in 1994. Former Portuguese colony Guinea-Bissau also uses the CFA franc.

ECOWAS’s five English-speaking countries—Gambia, Ghana, Liberia, Nigeria and Sierra Leone—each use their own legal tender. Portuguese-speaking Cape Verde trades with its escudo. French-speaking Guinea, the 15th ECOWAS member, uses the Guinean franc.

The currency divide has long been one of ECOWAS’s major stumbling blocks. Since 2000, however, six ECOWAS nations have been planning to introduce a common currency, known as the eco, in a new monetary union, the West African Monetary Zone (WAMZ). The long-term strategy is for the CFA to merge with the eco and transform into the region’s only currency.

This scheme raises many arguments about the merits of monetary unions, especially in light of Europe’s ongoing financial crisis. Monetary unions make regional trade simpler and ensure monetary stability by demanding prudential policy in member states, proponents say.

Such unions, however, fail to acknowledge the complexities of members’ individual economies, critics claim. They force domestic policymakers to fight economic battles with “one hand tied behind their backs”. One such critic is Sanou Mbaye, a former senior official at the African Development Bank. He blames the CFA, which is pegged to the euro, for making exports from CFA member countries more expensive than those of their competitors.

WAMZ was born in April 2000 at a summit in Accra, Ghana. Five ECOW- AS members—Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Nigeria and Sierra Leone—agreed to create a common central bank and currency by 2003, and then merge with UEMOA the following year. Liberia joined WAMZ in February 2010. Cape Verde, whose currency is pegged to the euro, is expected to join WAMZ once the eco is established. According to this plan, the eco would run parallel to the CFA franc until 2020, when all the ECOWAS countries would adopt one currency.

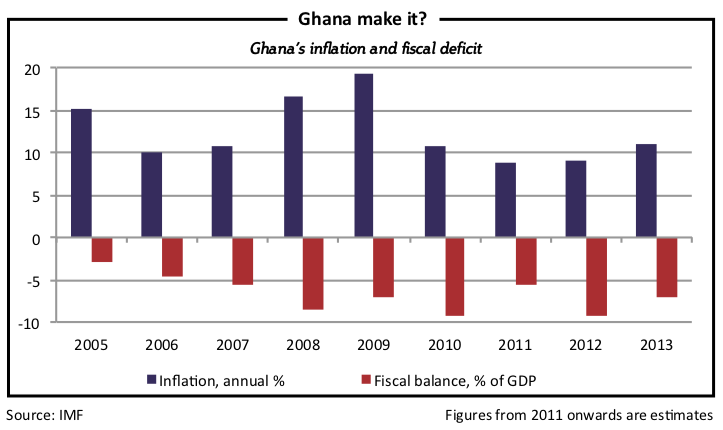

The body set up to make the technical preparations for the transition, known as the West African Monetary Institute (WAMI), has postponed this implementation several times. WAMI has been dragging its feet because most WAMZ members have failed to achieve the prescribed economic indicators needed for the smooth take-off of the common currency: single-digit inflation, central bank financing of government deficit of less than 10% of the previous year’s revenue, a government budget deficit of no more than 4% of GDP, and enough foreign exchange reserves to cover three months of imports.

As of June 2013, only Nigeria was close to reaching the required goals. Ghana is doing particularly badly: battling a fiscal deficit, double-digit inflation as well as other domestic and external headwinds, according to the IMF. Other WAMZ members have had similarly inconsistent records.

Considering Europe’s recent recession, however, the eco’s delay may be a blessing in disguise. The euro—the common currency among 23 European nations— has been besieged by the debt crisis in some parts of the continent, especially Greece.

The euro crisis holds lessons for Africa. Although the EU is an imperfect political union and has a monetary union coordinated by the European Central Bank, it does not have fiscal union. European countries still control their budgets and spending. Without this fiscal alliance, the EU was unable to overcome “asymmetric shocks”, where some unproductive countries, such as Greece, suffered downturns and needed fiscal help while others did not. It was difficult to discipline members who breached the pact.

“We are really learning from the euro crisis,” said John H. Tei Kitcher, WAMI’s acting director-general. “One lesson that stands tall is the need for individual countries aspiring to join monetary unions to be fiscally disciplined, transparent with their economic data with their peers and committed to converging to the agreed criteria.”

Fiscal discipline will help member countries to meet the convergence criteria and buffer them against potential shocks that could result from belonging to a monetary union. Such discipline requires a strong political commitment from member countries.

Another worrying issue is the dominant influence Nigeria would have on the zone. Nigeria’s population currently accounts for about 80% of the estimated 200m people residing in the WAMZ area and about 85% of the region’s $220 billion GDP, according to 2012 IMF data. Lastly Nigeria, a major oil exporter, benefits from higher oil prices, while its oil-importing neighbours suffer from these fluctuations.

Nigeria’s dominant size and strength within ECOWAS means smaller countries will have minimal say in exchange rate and monetary policy decisions. As a result, these countries will worry about a loss of sovereignty should ECOWAS launch a single common currency.

In addition, the policies and priorities of the region’s English- and French- speaking countries have diverged historically. Over the last ten years, the Anglophone countries have shown elevated inflation rates and pursued expansionary fiscal policies, while CFA countries have displayed marginal consumer price inflation and greater fiscal prudence. Each country will favour different approaches to exchange rate policy depending on whether it is import- or export-oriented.

“ECOWAS is just being overambitious,” says Femi Edun, a lecturer in the economics department at Lagos State University. “They still need to do more. There is need to get other things, such as infrastructure, manpower development, education, productivity. We really need to develop all these critical areas and the required capacity for us to start talking about [the] eco. The issue of [the] eco should come last, after all these issues have been addressed.”

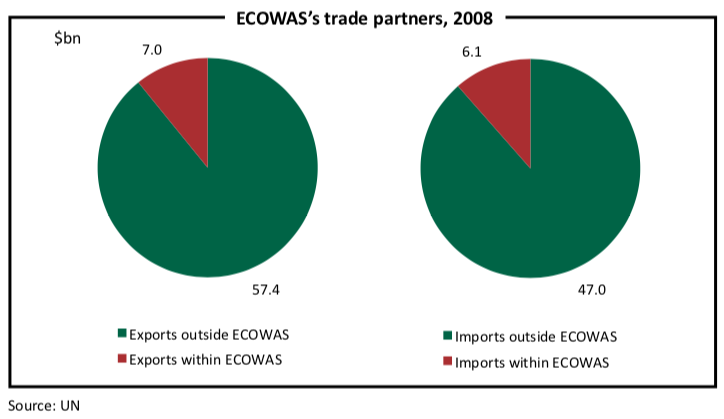

Another critical drawback is the paucity of commerce within ECOWAS. “A common currency makes sense if member countries have important intra-regional trade ties,” says Samir Gaidio, emerging market strategist at Standard Bank in London. “This is not really the case, as the primary trade partners of most ECOWAS nations are developed economies, and even emerging markets, including China.” For example, total trade with other ECOWAS countries is about 10%, he adds.

The formation of the European Economic Community and the European Free Trade Association was based on heavy trading between European states and the benefits that removing customs duties, tariffs and currency restrictions would bring to all the partners.

Africa, with minimal intra-regional trade, is not comparable. For example, in the ECOWAS region, intra-African trade, even in foodstuffs, is only a small percentage of national trade for most countries in the union, according to a 2010 paper prepared by the Overseas Development Institute, a UK-based independent think-tank.

Intra-African trade is depressed because the continent lacks industrialisation and is limited to exporting raw, unprocessed materials abroad. It lacks a large and sophisticated domestic market for semi-finished goods which can be processed further, and it lacks efficient storage facilities. Most importantly, Africa’s poor roads, bridges, railways, inefficient border posts and other transport networks, as well as faulty communications and unreliable and insufficient energy, result in high production and transaction costs.

English-speaking west Africa can learn from the European crisis. A viable monetary union needs similar production structures, flexible wages and prices, and symmetrical shocks hitting the economies. Unless underpinned by sound economic fundamentals and a credible plan for economic convergence, the eco will fail.

RONAK GOPALDAS is a director at Signal Risk, an exclusively African risk advisory firm. He was previously the head of country risk at Rand Merchant Bank (RMB) for a number of years, where he managed a team who provided the firm with in-depth analysis of economic, political, security and operational dynamics across sub-Saharan Africa. He holds a BCom degree in philosophy, politics and economics (PPE) and a BCom (Hons) from the University of Cape Town (UCT). He also has an MSc in finance (economic policy) through the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) in London.[