First, it was subsidised farming in the US and Europe and food dumping that pushed up prices and reduced food security. Now it’s a global food supply shortage that has tipped the scales in Africa and sparked an investment bonanza. The big question is: at what cost to food security?

In early summer, the sun is a flaming ball through the windscreen, while outside, silhouettes of people carrying fruit and vegetables file by. Here, dense green forests and grasslands carpet the hills and valleys. It is the middle of June 2006, and I am driving to see the farm manager of an agricultural processing plant on the rural outskirts of Uganda’s capital, Kampala. About 10 km outside the city, the main road takes you past Lake Victoria, into forested hills, before plunging into a scattering of decayed rural homesteads and impoverished villages strung around perennial rivers and tributaries that have carved out the valleys over centuries.

Beneath a thin belt of mist, women shuffle across the saddle of a hill into the valley to draw water from a tributary where cattle defecate. The women have no choice; their homesteads have no running water, no sanitation, no electricity, and no work. Every day, villagers walk up to 30 km to Kampala to sell fruit and vegetables grown on the open grasslands of the valleys. Some erect makeshift stalls along the thoroughfare; some fish from Lake Victoria, hoping for a decent catch of the area’s staple dish, tilapia.

After 10 km, the ungraded mud track reaches the crest of the hill. A few kilometres further, the sky turns bright yellow, and the landscape opens into a vast plateau of lush farmland. The focal point of your view is a hulking prefabricated processing plant laid out like a vast grandstand with its back turned to the valleys. Nearby, a cluster of brick tenements houses expatriate plant managers and technicians. The business is wholly owned and operated by the Indian pharmaceutical multinational Cipla. The area, the plant manager told me, is fertile ground for harvesting Artemisia, the active ingredient used in the manufacture of a Cipla patent to treat malaria.

“Anything will grow here. But nothing will grow without investment, and our presence here is an investment opportunity for us and Uganda,” he said, seemingly oblivious to the social neglect of this “showcase of investment opportunity”. Cipla is a model of globalisation muscled into Uganda: exploiting the area’s natural resources using expatriate labour, exporting the raw product abroad where it is manufactured into the anti-malaria drug at Cipla laboratories, then exporting the drug back to Africa, where malaria is a common affliction among mainly poor rural communities like the ones outside Kampala.

The Ugandan government understood the importance of foreign investment. During the 1980s, partly in response to structural adjustment measures of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), Uganda, along with other African countries, was “industrialised”. That is to say, it was a designated source of cheap raw materials as the government sought western capital and aid to underwrite its parlous economy.

Its former colonial authority, Britain, was the most enthusiastic backer. Capital poured in and, with the backing of the IMF, the colonial jargon of “cheap” commodities and “surplus” labour was dropped; the country was now a “showcase of investment opportunity”.

Yet, for all the capital inflows, the economy incurred annual net losses in the contribution of investment to Gross Domestic Product (GDP). While it lasted, President Yoweri Museveni, like many of his peers in the African Union (AU), made investments in agriculture and mining a trademark of his popular appeal. Uganda was open for business, he was fond of telling his interlocutors at multilateral gatherings, just not to locals.

I wanted to understand the thinking behind the theatrical façade of “investment” in agriculture that had become a miracle cure for hunger and poverty in most African governments’ policy avowals since the 1990s. What had gone wrong?

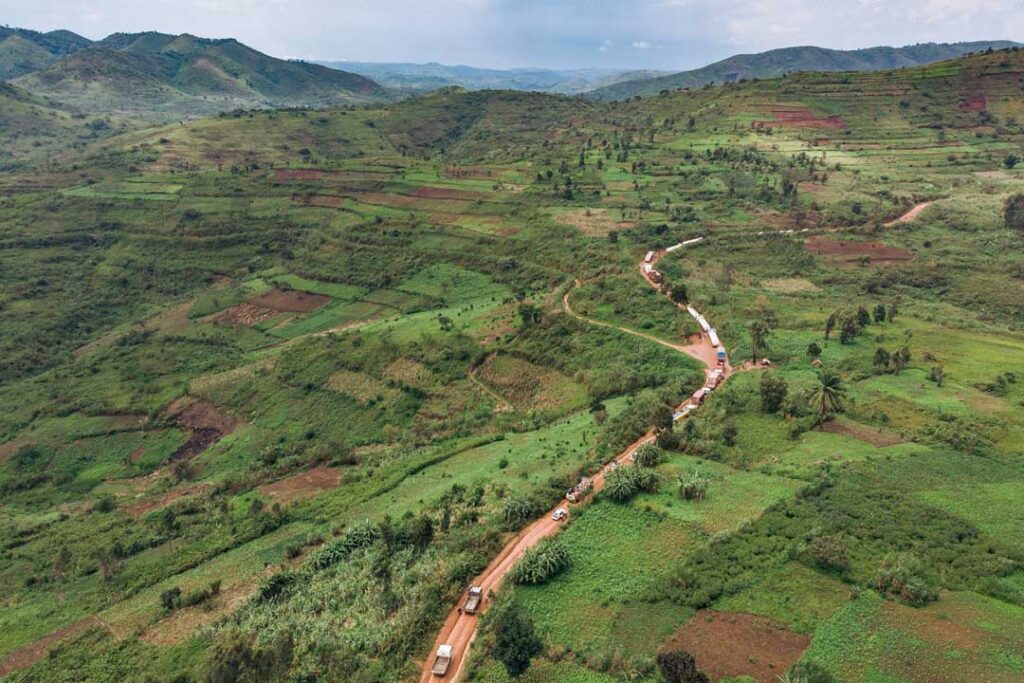

“You plant a stick in the ground, and something grows. But we don’t harvest the fruits,” Charles Mbire, a Kampala businessman, told me when I offered up the Cipla manager’s remark. This was only partly true. The real story was that investment in Uganda’s rich agricultural assets was not without substantial foreign representation. When I visited Kampala in 2006, British, Indian, and Chinese firms were muscling into the economy’s agriculture sector. Those locals fortunate enough to be employed were paid just enough to keep their families alive. Along the main thoroughfare to Kampala there was something symbolic about the daily journey of rural villagers. The paradox—the desolation of impoverished communities and the lucrative farmlands and hulking processing plants—said much about the model of agricultural investment.

The truth is that Uganda, like other African countries with strong agricultural potential, was failing because the model of subsidised farming and food processing in the West had been succeeding. Consider a continent with some 800 million hectares of arable land lying largely fallow because governments in the US and Europe could use their market dominance to subsidise their farmers or simply dump massive quantities of processed food to keep the consequences of technological efficiencies – surplus product – in check. That may have literally been easy to swallow two decades ago if you were a consumer reading these words from the aisle of a bustling supermarket in the plush Upper West Side of New York City or Paris where food prices had been heavily subsidised. It may have been even easier to imagine if your farm in the American mid-West continued to receive buckets of cash from the government to shield the agricultural industry from cheaper exports. Of the 58 developed countries surveyed by the World Bank in 2009, 48 had imposed price controls, consumer subsidies, restrictions on imported food, or lower tariffs.

Then, two years after my visit to Kampala, the prolonged period of abundance and low prices in advanced economies took their toll, laying the groundwork for an inflationary spiral that is still silently ticking over into a full-blown global food crisis. Data from the World Bank and the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development’s World Investment Report 2022 suggests that food supply is, in fact, entirely out of kilter with demand, and subsidies in Europe and the US are adding unsustainable upward pressure on prices. If that were not enough, soaring oil prices and biofuels are conspiring to make sure that this particular financial unravelling will play out over a prolonged period. The difference these days is that investors are on the prowl for high-yield harvests to exit the damage wrought by the massive speculative binge that plunged the world economy into red ink in 2008. Their sights are on fertile, untapped land in equatorial Africa, where, according to the UN’s World Investment Report 2015, investment still trails the rest of the world.

Over the past few years, investment firms like Emergent Asset Management, Britain’s Chayton Capital, the US’s Global Environment Fund, as well as homegrown players like South Africa’s Development Bank for Southern Africa, Sanlam Private Equity and SP-aktif, both of which have raised $400 million for the Agri-Vie Fund, Ghana’s Databank Financial Services, Kenya’s Amani Capital in a joint venture with the Norwegian Investment Fund for Developing Countries (Norfund), and Uganda’s Gatsby Charitable Foundation, set up by the Rockefeller Foundation, have been eyeing agro-industrial companies and lobbying African governments to back joint ventures and buyout-related investments in the continent’s $280 billion per annum agriculture sector. “It’s a simple matter of funds scouring the earth for the best value deals. And today they’re funding them in Africa’s agribusiness,” the World Economic Forum’s (WEF’s) chief economist John Page told a WEF gathering in 2017.

That potential is not an advertising script for the evening news. The agriculture sector in Africa accounts for 60% of the world’s unused arable land at a relatively low average level of soil degradation and relatively good weather conditions, of which only 3% is irrigated, compared to 20% globally. Less than 10% of land in Africa is cultivated, and 80% of farms are less than two hectares in size. Farm yields are around 1.2 tonnes per hectare, compared to an average of five tonnes globally.

At a time when land and hunger in Africa have become synonymous, establishing food security, particularly household food security, is widely acknowledged as an important milestone in advancing the living standards of the poor. Yet the deals so far have been controversial; in recent years, African politicians have routinely railed against “vulture capitalists”. Even the business-friendly World Bank recently warned investment funds that they needed to behave responsibly.

But will they? Notwithstanding the recent investment stampede, the number of malnourished people globally has increased from under 100 million before the 2008 global financial crisis to approximately one billion before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, with 80% living in Africa. This demonstrates that investment in farming and food production does not necessarily imply an equitable and proportionate distribution among African countries and people at the household level. In fact, by 2015–16, sub-Saharan Africa had been losing market share in global agriculture exports. According to the 2017 World Competitiveness Report, the top exporters of agricultural commodities were the Ivory Coast, Ghana, Nigeria, Kenya, Ethiopia and South Africa, all of which lost market share despite increasing their exports in absolute terms.

That’s partly because of low agricultural productivity, which in turn has made agriculture on the continent economically impoverishing and technically unsustainable. But there’s a larger, macro-level reason: the absence of scalable and diverse markets capable of extracting benefits from international trade.

Since the AU adopted the Africa Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA) as a blueprint for integrated trade and growth, little has been done to implement the economic reforms the AfCFTA Secretariat has recommended. In the face of competing economies in the West and the costly burden of structural rigidities and scalable markets, the AfCFTA plan is to deregulate labour markets, slash red tape, and boost competition on the continent. But only a poorly handled overhaul has been attempted.

It is not that those pioneering the AfCFTA agenda haven’t tried. The problem, as the academic Ian Taylor has written, is that the idea of putting 800 million hectares of arable land to productive use may be undermined by trade barriers that make agriculture and food production a tough act in African countries. To put that in perspective, by some estimates, about 97% of African businesses are small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) that provide at least 50% of employment and account for 70% or more of GDP growth. Yet the biggest hassle factors in agriculture, identified by the AfCFTA, have been high transaction costs, driven by weak physical infrastructure, widespread information asymmetries, low levels of marketed surplus, and high export taxes.

There are significant macro-regional implications as well, like the reality that the economic architecture for scalable agricultural and food processing markets is sclerotic. Indications are that the seven Regional Economic Communities (RECs) and the African Economic Community, formed in 1991 following the Abuja Treaty, are hardly solid foundations for inter-continental trade and sustainable investment in the sector.

What, then, is the way forward? With rising food prices on the back of global supply shortages, the ongoing investment stampede in the agriculture sector is a potential Vitamin B shot for the continent. The solution, economist Iraj Abedian has argued, is in the identification of regional comparative advantages that could harmonise trade between individual countries and businesses in the agriculture value chain, and ultimately help reconfigure and integrate the present geo-political boundaries of the AU’s seven RECs.

“The problem with the present setup,” Abedian says, “is that regional boundaries are mapped onto inherited colonial boundaries rather than a value chain that makes economic sense. Put economic participants in the value chain—from farming in countries with arable land to food processing in countries with strong manufacturing capacity—and in the rough and tumble of business, they will fall together within economic boundaries by virtue of sectoral advantages.”

Indeed, the case for remapping the economic contours of farming and food production under the AfCFTA rests on economic pragmatism. Abedian urges us to consider fertile agricultural opportunities in, say, Uganda, as one of those advantages: “If technological and research inputs into seed banks and food processing capacity are supplied by, say, South Africa to countries with natural agricultural endowments like Uganda, the results could be an uptick in farming and food production with benefits for food security on the African continent and massive export opportunities.”

In such a scenario, a scalable market would arise from an integrated agricultural value chain. The AfCFTA agenda, in a global context of rising food scarcity and soaring prices, is an opportunity to institutionalise a process that burst onto the scene in 2008. But can the AfCFTA initiative meet the challenge? What seems clear enough is there is, for the first time, a sense of forward momentum – from moribund bilateral trade relations with the West and the portentous declarations and institutional lethargy of the AU, to the real building blocks of agriculture: intra-African trade.

Malcolm Ray is a research consultant and author of two scholarly books, titled Free Fall: Why South African Universities are in a Race against Time and The Tyranny of Growth: Why Capitalism has Triumphed in the West and Failed in Africa. Malcolm’s subject speciality is economic history. His writing deals directly with themes of power hierarchies, race and gender discrimination, and class inequality. His current work focuses on the shifting dynamics of urban livelihoods, economic growth and power relations that allow for the development of theorisations of the economy and polity more relevant to post-colonial contexts. Malcolm began his career as an anti-apartheid activist during the 1980s and early 90s. He practised journalism for more than a decade before becoming a financial magazine editor in the early 2000s. He was a Senior Fellow in the Faculty of Humanities at the University of Johannesburg and editor of four premier South African and pan-African business and finance magazines.