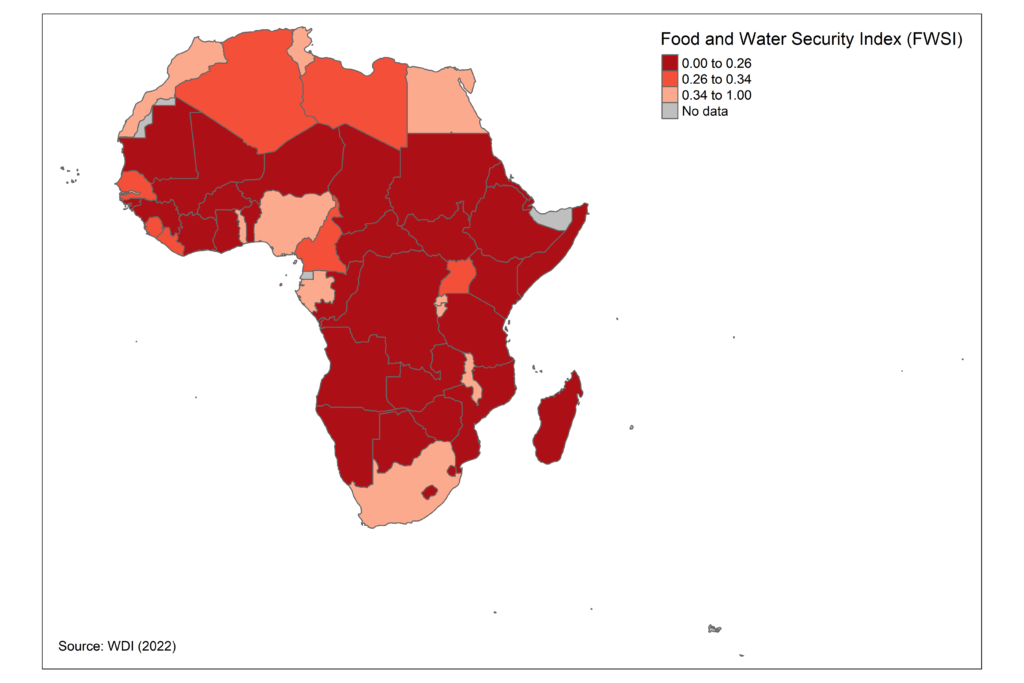

The African food and water security landscape faces a significant challenge. Despite its vast agricultural potential and abundant water resources, the continent continuously faces issues of hunger and water scarcity. This is clear from the mean value of 0.26 on the food and water security index, with many countries falling below this mark (Figure 1). The index operates on a scale from 0 to 1, where higher scores denote better security. To tackle these issues, it is vital to leverage, among other things, data-driven approaches that can enhance agricultural planning, resource allocation, risk management, and overall governance.

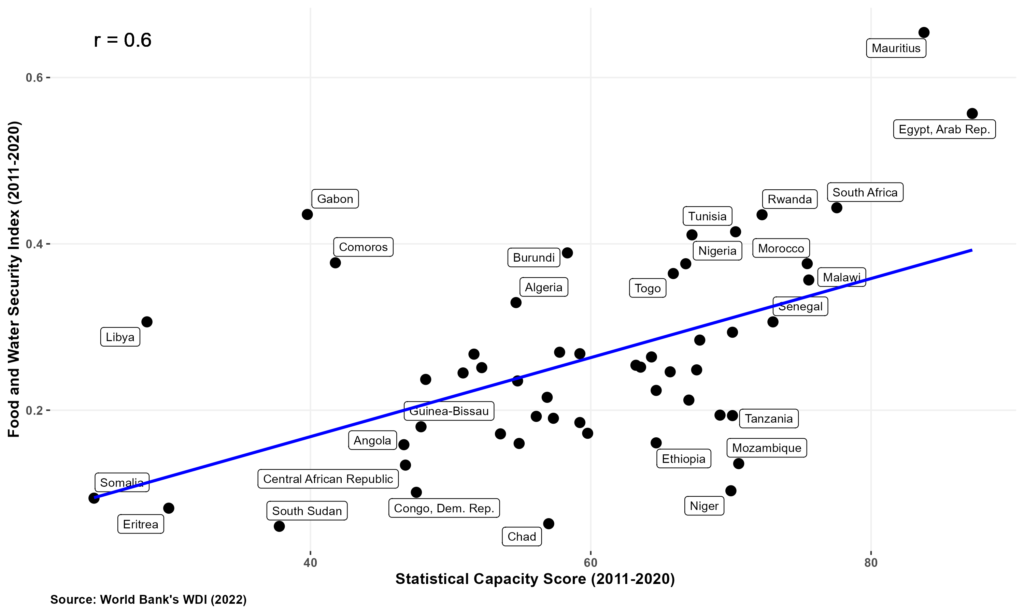

In recent years, there has been a surge in the use of data for evidence-based decision-making and predictive analysis. Unfortunately, as the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) notes, agricultural statistical systems and data are in a sorry state in many African countries. As illustrated in Figure 2, enhancing food and water security governance and outcomes in Africa hinges on substantial improvements in the statistical systems of African nations.

To investigate the relationship between statistical systems and food and water security governance in Africa, the food and water security index incorporated multiple indicators from the World Bank. Given data constraints, the food security indicators focused on food availability. Each indicator was weighted according to its significance and contribution to Africa’s food and water security based on literature in this field. The weighted indicators included:

Food security indicators

- Cereal yield (kg per hectare) (25%)

- Arable land (% of land area) (25%)

Water security indicators

- Renewable internal freshwater resources per capita (cubic metres) (20%)

- People using at least basic drinking water services (% of the population) (15%)

- People using at least basic sanitation services (% of total population) (15%)

Statistical capacity, on the other hand, is, as the World Bank puts it, a nation’s ability to collect, analyse, and disseminate high-quality data for evidence-based decision-making. This and other data sets used for the analysis were obtained from the World Bank.

Figure 1: Food and water security scores of African countries (2011-2020)

A significant correlation emerged from examining the bivariate relationship between the food and water security index and the statistical capacity score of African countries over the past decade. The scatterplot revealed that African countries that had strong statistical capacity or systems over the past decade exhibited better food and water security governance and outcomes, with a correlation of 60%. Conversely, African countries with poor statistical systems had lower food and water security outcomes over the past decade.

These results remained consistent after controlling for variables such as GDP per capita, population size, and an index of governance quality encompassing government effectiveness and control of corruption in multivariate regression analysis.

By way of analogy, consider the practices of experienced farmers who strategically rotate crops to maintain soil fertility. Just as these farmers use data on crop growth and soil conditions to inform their planting decisions, data-driven approaches rely on information to optimise agricultural planning, resource allocation, and risk management. In both cases, the goal is to maximise efficiency and productivity while minimising risks.

The implications of these findings are substantial. Africa possesses abundant agricultural and water resources and potential, making it possible to eliminate food and water insecurity. However, realising this potential necessitates improving and harnessing data-driven approaches, among other things.

One of the key benefits of this approach is its ability to enhance agricultural planning. With accurate and up-to-date data, policymakers can make informed decisions regarding crop selection, planting schedules, and resource allocation. This can lead to increased agricultural productivity and a reduction in food shortages.

Figure 2: The relationship between statistical capacity and FWSI in Africa

Moreover, data-driven approaches aid in resource allocation. By identifying areas with the highest levels of water stress or food insecurity, governments can allocate resources more efficiently to target those in need. This targeted approach ensures that resources are used where they are most needed, reducing waste and inefficiency.

Risk management is another area where data-driven governance shines. By collecting and analysing historical data, governments can predict and tackle potential food and water security crises. This approach allows for timely interventions, such as drought-resistant crop cultivation or water conservation measures, to be implemented, reducing the impact of disasters.

Overall governance is also enhanced through data-driven approaches. Accurate data empowers policymakers to monitor progress, track the effectiveness of interventions, and adjust strategies as needed.

Egypt and South Africa are examples of African countries with strong statistical systems that have exhibited better food and water security governance and outcomes in the past decade.

Egypt, facing extreme water scarcity, relies heavily on external freshwater sources, primarily the Nile River, for most of its water needs. To address this challenge, Egypt uses digital technologies, including moisture sensors, for real-time water monitoring, such as tracking water pressure and quality, which in turn reduces water waste. As the African Union Development Agency notes, these digital sensors, which can be placed in the soil, measure moisture levels and transmit data to policymakers and farmers via smartphones, aiding timely and efficient decision-making.

In South Africa, Statistics South Africa, which is the country’s statistics agency, regularly collects, processes, analyses, and reports data on food and nutrition security to inform decisions on government initiatives in this area. This process involves providing information on the extent of households’ experiences of hunger and access to food and providing insight into the location and profile of households that are food and nutrition insecure.

In the words of the late actor Peter Ustinov, echoed by Nigerian academic Emefiele Ezeani, the point of living, and of being an optimist, is to be foolish enough to believe that the best is yet to come, even when little or nothing is changed. Despite the challenges that persist, African countries have the potential to overcome food and water insecurity through data-driven approaches. These approaches are key to unlocking the continent’s agricultural potential and improving the well-being of its citizens.

Nnaemeka is a Senior Data Analyst at Good Governance Africa. He holds a Master’s degree in e-Science (Data Science) from the University of the Witwatersrand, funded by South Africa’s Department of Science and Innovation. Much of his research explores socio-political issues like human development, governance, bias, and disinformation, using data science. He has published research in scholarly journals like EPJ Data Science, Politeia, the Journal of Social Development in Africa, and The Africa Governance Papers. He has experience working as a Data Consultant at DataEQ Consulting. He has also taught at the Federal University, Lafia (Nigeria) and the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg (South Africa).