Most Africans want the news media to investigate and report government mistakes and corruption. However, in African countries with higher corruption levels than lower ones, citizens are more concerned about the harm excessive reporting brings to their country.

Over the past few decades, corruption has been an endemic issue confronting many African countries. The media is instrumental in combating corruption through investigative journalism, informing the public, and promoting accountability, as demonstrated in African countries like South Africa, Ghana, and Nigeria.

For instance, in South Africa, news reports on large-scale corruption and clientelism at the highest levels prompted the Office of the Public Protector (an independent ombudsman) to investigate the allegations. This investigation led to the 2014 Nkandla report and the 2016 State Capture report, which found unethical and illegal activity by the then President Jacob Zuma, which contributed to his decision to resign in February 2018.

This article is driven by two fundamental questions: What do Africans think about media involvement in investigating and reporting corruption? And how do these perceptions vary across countries with differing levels of corruption control?

To answer these questions, I used the latest World Bank “control of corruption” data for the year 2022 and Afrobarometer Round 9 survey data covering 39 countries and conducted from 2021 to 2023. Afrobarometer is a non-partisan research network that provides reliable, nationally representative survey data on Africans’ experiences and evaluations of democracy, governance, and quality of life.

In my analysis, I focused on question 17, which asked a sample of 54,436 Africans to pick which was closest to their view between:

Statement 1: The news media should constantly investigate and report on government mistakes and corruption.

Statement 2: Too much reporting on negative events, like government mistakes and corruption, only harms the country.

The respondents chose from the following options: “Agree very strongly with 1”, “Agree with 1”, “Agree with 2”, “Agree very strongly with 2”, ‘Agree with neither”, and “Don’t know.” For the analysis, I pooled “Agree very strongly” and “Agree” for each statement and excluded the remaining 2% of responses.

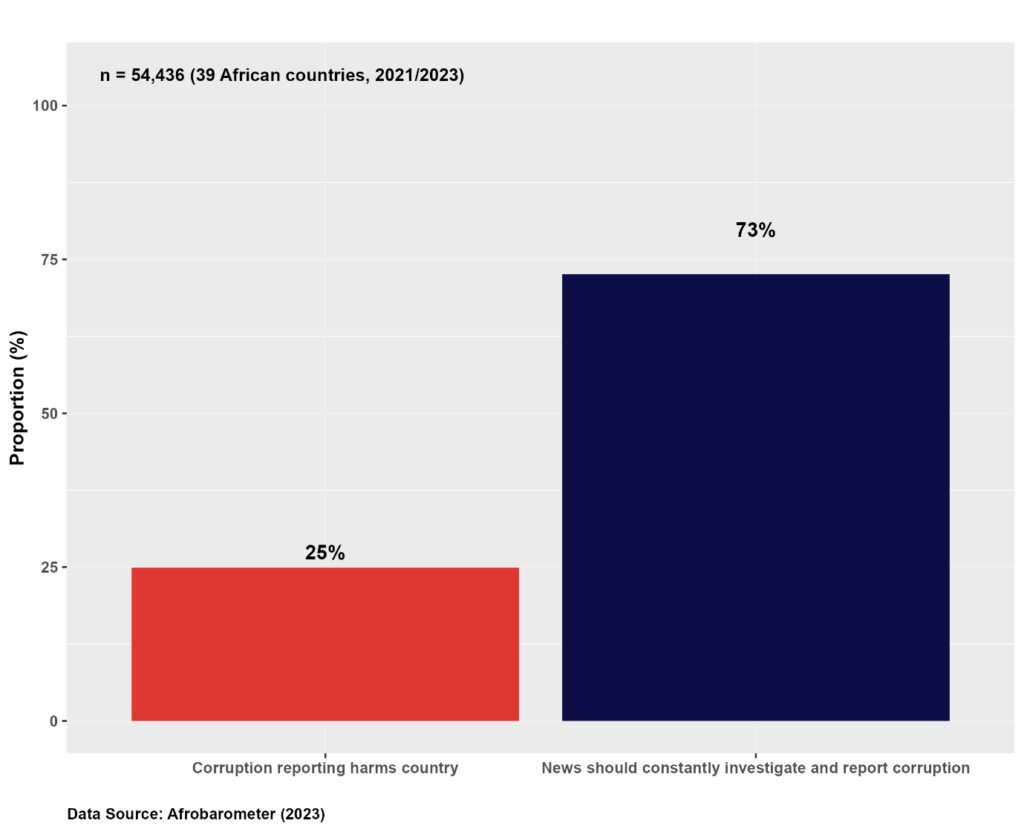

Figure 1: Perceptions of the news media in corruption investigation and reporting

To start with, I wanted to understand how much Africans support news media involvement in corruption investigation and reporting. Figure 1 shows that 73% of respondents want the media to constantly investigate and report government mistakes and corruption, while 25% think too much of such reporting only harms their countries.

This divergence stems from various factors. Some Africans may view news media scrutiny as essential for transparency and accountability in government; thus, they support it as a key aspect of a thriving democracy. Conversely, others might perceive excessive media focus on government mistakes and corruption as detrimental, potentially undermining national stability and progress. In Figure 2, I wanted to understand how these responses varied based on the latest World Bank’s ranking of the countries on corruption control.

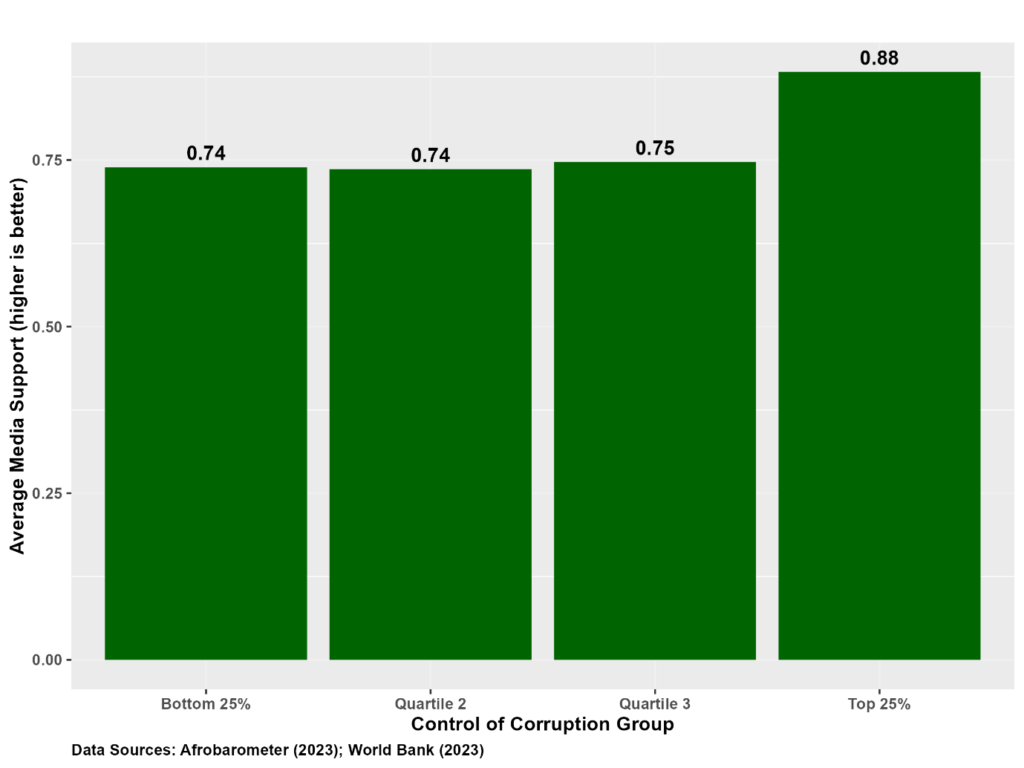

Figure 2: Average Sentiment Towards Media Involvement by Corruption Quartiles

By grouping 54,436 respondents into four quartiles according to their country’s latest control of corruption scores and averaging responses in each quartile, we can see how moving from the lowest-performing to top-performing groups corresponds with increased support for media interference. This distinction is more pronounced when comparing the top-performing control of corruption group with the lower half of countries. Specifically, the average support for media-led corruption investigation and reporting among the top 25% of countries in corruption control is 14% higher than that observed in the bottom 50%.

In essence, on average, in African countries with lower corruption control than higher ones, citizens are more worried about the harm too much media scrutiny may cause their country. This finding remained consistent after controlling for two potentially confounding factors using regression analysis: GDP per capita (which measures economic size) and the population size of those countries in 2022.

This finding is likely because, in African countries with stronger corruption control, people trust that the media operates independently and can play a vital role in holding corrupt public officials accountable, as seen in the South African case. Conversely, in countries with lower corruption control, such as Zimbabwe, people worry that such scrutiny could worsen instability, deter investment, and be used for political agenda rather than genuine reform. In Figure 3, I unpacked the variations in responses across the 39 African countries surveyed by Afrobarometer.

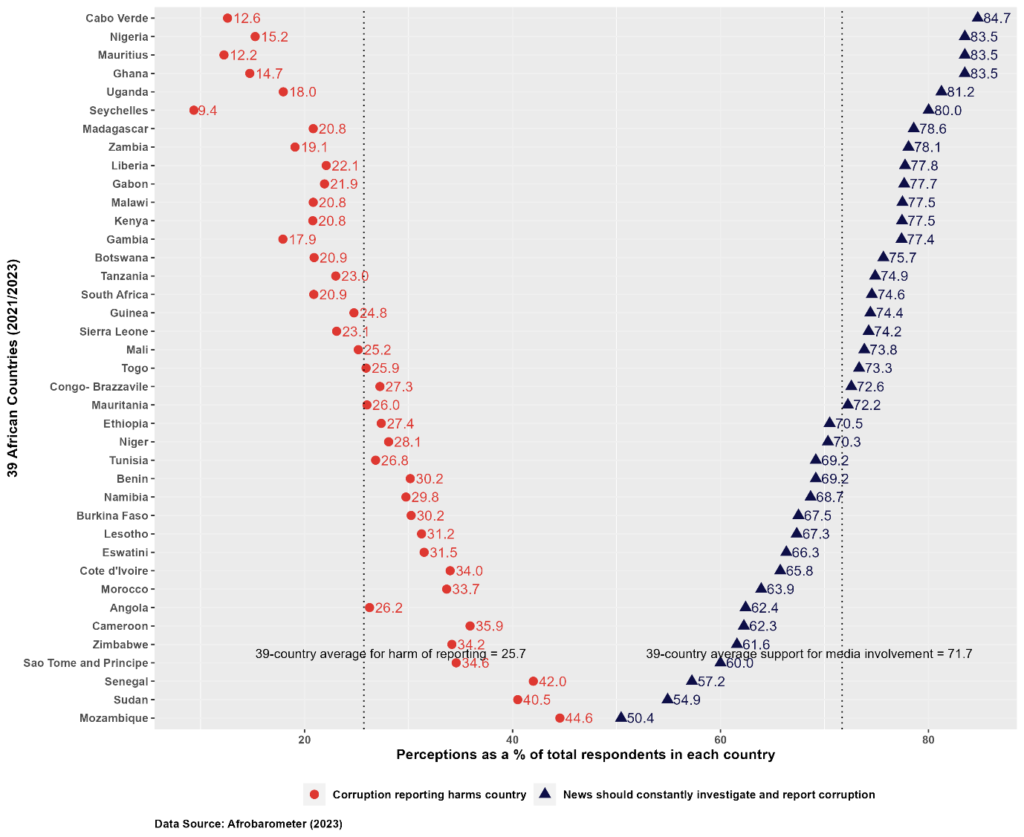

Figure 3: Perceptions of news media involvement in corruption probe by country

Figure 3 shows that there is wide variation at the country level in how Africans view news media investigation and reporting of corruption and government mistakes. In all the surveyed countries, more than half of the respondents wanted the news to probe government mistakes and corruption. However, 20 countries surpassed the 39-country average of 25.7% for excessive reporting concerns. This indicates a higher proportion of citizens in these countries who view excessive media scrutiny as detrimental compared to the overall average.

Precisely, in countries with widespread corruption, such as Zimbabwe and Sudan, citizens were more concerned that such investigation harms the country than in countries with lower corruption levels. Due to a history of political repression, economic fragility, and fear of politicisation in Zimbabwe, for example, people worry that such scrutiny could worsen instability, discourage investment, and be used for political motives rather than genuine reform.

Similarly, in Sudan, plagued by a long history of conflict, displacement, political and economic instability, vicious power struggle, and repression under the current military government and past ones, citizens may fear the worst if the military government’s mistakes and corruption are excessively exposed. With the populace already scarred by harsh political and economic conditions and nearly 8 million displaced due to the recent power struggle and violent clashes within the military government, citizens may fear the potential repercussions of media scrutiny and reporting on government misconduct.

Taken together, the data highlights the nuances in how Africans view media involvement in corruption investigation and reporting. While there is widespread support for such scrutiny, variations exist based on corruption control levels. Stronger control correlates with higher support, reflecting trust in media independence and its role in accountability. Conversely, in countries with lower control, concerns about potential economic and political harms from excessive media scrutiny persist.

Nnaemeka is a Senior Data Analyst at Good Governance Africa. He holds a Master’s degree in e-Science (Data Science) from the University of the Witwatersrand, funded by South Africa’s Department of Science and Innovation. Much of his research explores socio-political issues like human development, governance, bias, and disinformation, using data science. He has published research in scholarly journals like EPJ Data Science, Politeia, the Journal of Social Development in Africa, and The Africa Governance Papers. He has experience working as a Data Consultant at DataEQ Consulting. He has also taught at the Federal University, Lafia (Nigeria) and the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg (South Africa).