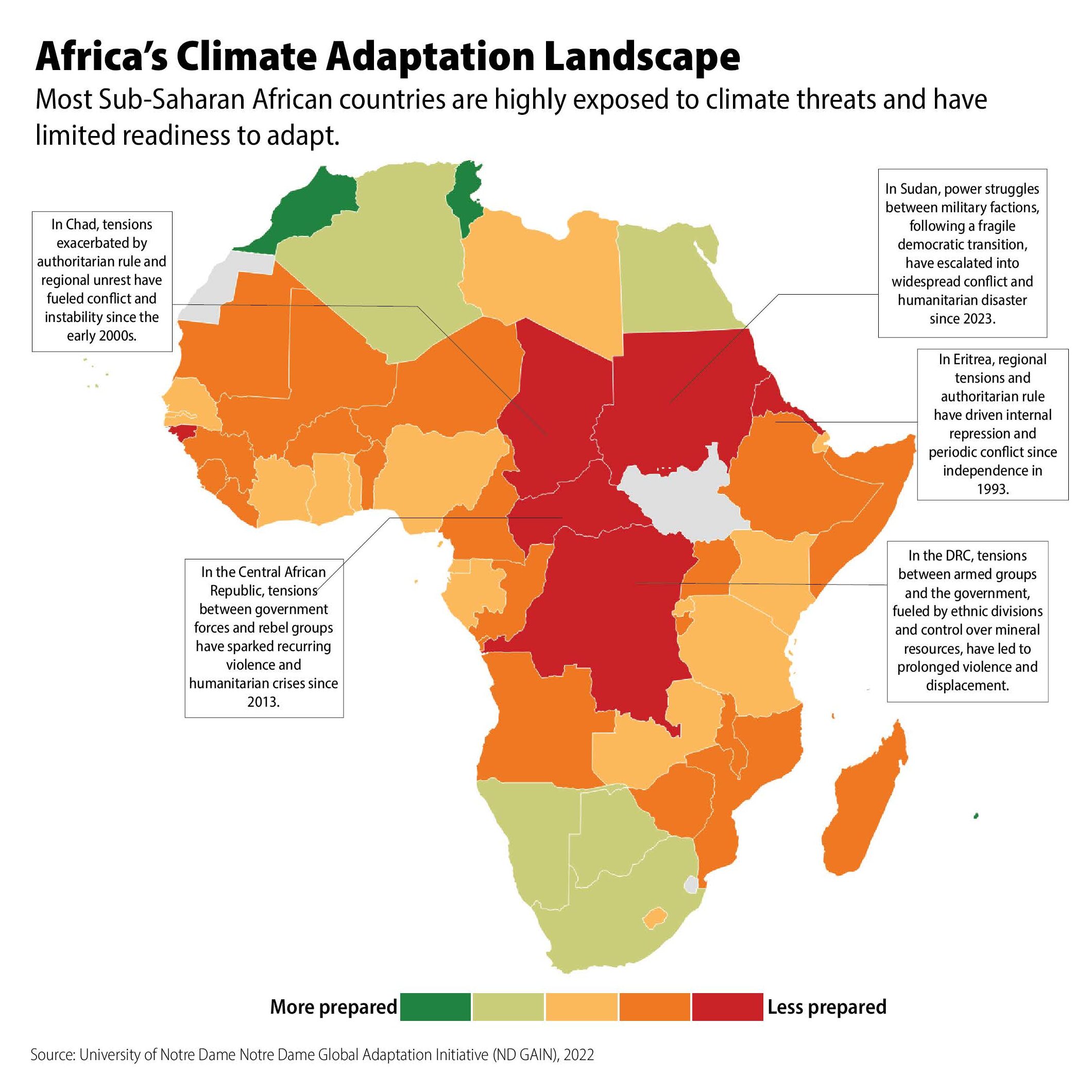

Across Africa, extreme weather events disrupt daily life, threatening livelihoods and worsening human security conditions. When conflict occurs in regions already highly exposed to climate shocks, it aggravates existing vulnerabilities and accelerates the breakdown of social, economic and ecological stability. As extreme weather events continue to intensify, these vulnerable and fragile states bear the burden of compounded events that threaten to erode adaptive capacities, degrade environmental resources and destabilise the institutions responsible for protecting vulnerable populations from climate-induced risks.

In South Africa, deadly and destructive flooding in the Eastern Cape, particularly impacting Mthatha, occurred in June this year. Meanwhile, five other countries in the region, including Lesotho, Malawi, Namibia, Zambia and Zimbabwe, declared national drought disasters following some of the worst dry spells experienced in 2024. In East Africa, exceptionally long and heavy rains between March and May led to severe flooding in Kenya, Tanzania and Burundi, while tropical Cyclone Jude compounded this flooding in March. Meanwhile, several countries in North Africa reported another consecutive year of below-average harvests. These extreme weather events are gradually becoming erratic and redrawing Africa’s conflict map in unpredictable ways.

According to a new report from the World Meteorological Organization (WMO), many African states bear an increasingly heavy burden from climate change and disproportionately high costs for essential climate adaptation.

Climate-induced insecurity is increasingly emerging as an environmental crisis and a core challenge to broader insecurity on the continent. This is because climate vulnerability acts as a threat multiplier, amplifying resource scarcity, triggering displacement, and eroding institutional resilience across sectors. When climate vulnerability and conflict intersect, states often face a dual crisis in which extreme climate variability strains already scarce resources, intensifies competition and undermines social cohesion. Conflict, in turn, displaces populations and destabilises institutional capacity, deepening vulnerabilities.

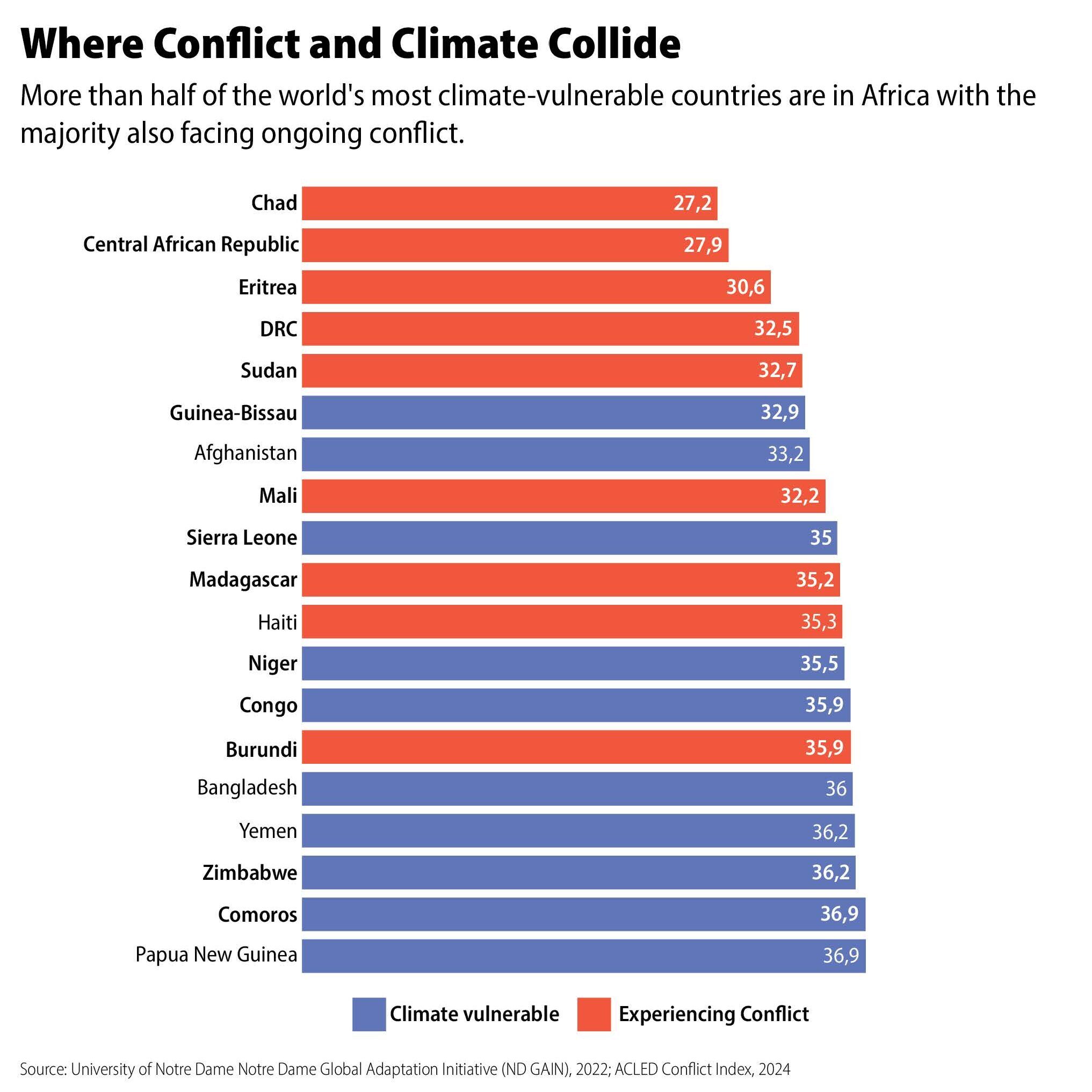

This dynamic between conflict and climate risk creates a vicious loop that compounds and exacerbates fragility, locking communities in a relentless cycle of insecurity, displacement and governance collapse. Today, of the countries worst hit by extreme weather events, more than half were also experiencing some form of conflict. Out of the 15 countries most vulnerable to climate change, 12 are struggling with violent conflicts. These include South Sudan and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), two of Africa’s most conflict-exposed regions, grappling simultaneously with acute climate stress.

These overlapping crises point to a worrying trend in which regions facing extreme climate variability and resource stress tend to experience elevated rates of conflict and insecurity (Burke et al., 2024). In fragile or conflict-affected settings, ongoing instability can severely undermine adaptive capacity by destroying infrastructure, weakening institutions, and diverting resources from climate resilience efforts. Research shows that active or recently active conflict zones show lower implementation rates or effectiveness of adaptation programmes (Siyati et al., 2021). At the same time, inadequate adaptation to climate risks such as drought, flooding, or unpredictable agricultural zones can lead to and intensify competition over scarce natural resources like land and water, heightening the potential for social tension and conflict. This dynamic creates a symbiotic negative feedback loop where climate stress worsens conflict, and (as a result) conflict further erodes the ability to adapt to those stressors.

When conflict takes hold in regions vulnerable to extreme weather shocks, it further degrades the physical and institutional infrastructure necessary for climate adaptation. Critical infrastructure like early warning systems, irrigation and seed distribution systems and agroforestry are often incapacitated. Moreover, the presence of conflict also erodes institutional capacity. Local governance systems and natural resource management frameworks are frequently disrupted or destroyed. The collapse of these vital infrastructures leaves governments and aid organisations unable to buffer, plan, finance and implement climate-resilient initiatives against climate shocks.

In countries most vulnerable to extreme weather shocks and conflicts, an increase in competition over natural resources becomes more likely. For example, countries like the DRC and South Sudan highlight how competition over ownership in extractive industries is compounding crises by fuelling harmful emissions and embedding instability. Elsewhere, as arable land, pasture, and water become less available, interpersonal tensions and local disputes intensify, and cooperative resource management is undermined. Tensions over vital water systems, as seen in the Lake Chad basin and the Nile River, highlight how environmental stress and political tensions become entangled and escalate insecurity. These overlapping pressures often weaken natural resource governance, reducing the effectiveness of institutions tasked with managing land, water, and biodiversity.

When land, water and biodiversity are not managed well, the consequences are often widely felt. Displacement rises, hunger worsens, and critical governance infrastructure is compromised. This further contributes to the breakdown of societies. Adaptation becomes more difficult, feeding back into a cycle of fragility and crisis. This vicious loop is starkly visible in contexts like South Sudan or Somalia, where both conflict and climate risks are extreme.

The consequences of these impacts are also not equally shared. Subsistence farmers, pastoralist groups, and women and youth in fragile or marginalised areas disproportionately face the brunt of this compounded exposure to both environmental shocks and violence. This is because these communities often have the least, or lack, access to political representation, land rights, early warning systems, and formal adaptation support. This results in further exclusion from climate governance and peacebuilding processes, leaving them exposed and vulnerable to various risks and undermining resilience and sustainable peacebuilding. In addressing this interconnected relationship and compounded effect of climate vulnerability and conflict, responses must address both climate resilience and conflict prevention as interconnected policy priorities.

As conflict weakens local institutions, disrupts community-based natural resource governance, and damages critical infrastructure, these disruptions make it incredibly challenging to implement effective adaptation strategies. In other words, if one envisions conflict as a fire, climate vulnerability would be dry wood that creates the conditions for conflict to thrive, and weakened government institutions are the incapacitated fire brigade unable to respond to the blaze.

Paradoxically, these areas most in need of climate finance and often conflict-affected are the least likely to receive it. Potential opportunities for funding, including international climate finance mechanisms and bilateral aid agencies, often avoid high-risk zones. Reports from the African Development Bank further highlight how conflict zones are routinely bypassed, not because of a lack of need, but because of institutional caution. This trend reveals a growing governance dilemma in which climate resilience requires investment; however, current funding frameworks and adaptation strategies tend to be inadequate in precisely those areas.

While limited, some integrated initiatives are beginning to acknowledge the dual risks of conflict and climate change. For example, the Lake Chad Basin Commission has coordinated efforts among regional members towards collaboration on sustainable water governance to reduce the likelihood of water conflicts in central Africa and support peacebuilding across borders (ACCORD, 2023/4). Similarly, drought crisis management systems such as those seen in the Sahel have improved community preparedness by combining traditional knowledge with satellite data. These examples show that where governance, environmental management, and security are approached together, gains are possible.

However, despite this, current climate finance systems and adaptation strategies are not designed with fragility in mind. Top-down aid disbursement, long bureaucratic cycles, poor regional collaboration and a heavy focus on large-scale infrastructure often bypass the informal but effective systems that operate in conflict zones.

Instead, climate funding mechanisms and adaptation policy must adopt a conflict-sensitive design that targets supporting smaller, community-led interventions that build resilience and adaptive capacity at the local level. Channelling funds through local NGOs, investing in institutional rebuilding, and integrating climate adaptation into peacebuilding frameworks will ensure efforts are not just reactive but transformative.

As climate extremes intensify and institutions strain under pressure, it becomes increasingly clear that resilience and peace cannot be pursued in silos. The convergence of climate shocks and conflict across Africa is neither incidental nor isolated – it is structural, reinforcing, and deeply destabilising. Understanding this relationship is not only essential for better policy; it is essential for the continent’s future stability. This interdependence redraws the map of insecurity in ways that demand fresh thinking. Recognising and responding to this climate-conflict nexus is vital if we are to break the cycle of fragility and forge a more stable path forward.

Mischka Moosa is a data journalist at GGA. She holds a Bachelor of Social Science with majors in Gender Studies and Political Science that she obtained from the University of Cape Town. Her focus of interest is on decolonial approaches to justice, development and transformation in Africa.