The “wave of democracy” that swept sub-Saharan Africa after the Cold War faced widespread scepticism, with many viewing it as mere “window dressing” to satisfy Western aid donors. Yet three decades later, as Professor Rod Alence of Wits University notes, African democracies outperform autocratic ones in delivering good governance.

Democracy transcends voting – it is a continuous process of public participation, accountability, and transparency. It requires robust institutions and an engaged civil society to thrive. Authentic deliberation and open debate are vital in transparently shaping decision-making processes. Academics Stephan Lewandowsky and John Cook note that one reason we trust democracy as a system of governance is its ability to deliver “better” decisions and outcomes than autocracy. This is driven by the idea that the “wisdom of crowds” outperforms any one individual.

Natural resource governance is one of the key areas where democracy could offer citizens a voice in policymaking. Many African countries are rich in natural resources like oil, minerals, and timber, yet these resources often fuel corruption, conflict, and environmental degradation – what many scholars call the ‘resource curse.’ In more democratic settings, where citizens, civil society organisations, the media, and opposition parties can hold leaders to account, there is a greater chance that natural resources will be better managed, and citizens can get more from their government.

In Botswana, for example, diamond wealth has been better managed and more equitably distributed through accountable institutions. However, in less democratic countries, resource wealth is often captured by elites and multinational corporations, with ordinary citizens excluded from decision-making processes. This may fuel corruption, stifle development, and create social unrest.

The promise of democracy is that it allows people to influence decisions that directly impact their lives and communities. When citizens can participate in the democratic process (through elections, protests, community engagement, or civic forums), they can better demand that resource extraction serves the public good. This question – whether democracy increases Africans’ voice in natural resource governance – is underexplored and is what this article seeks to answer.

To do this, I analysed the latest Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) “liberal democracy” data for 2022 and Afrobarometer Round 9 survey data covering 39 African countries and conducted from 2021 to 2023. Afrobarometer is a non-partisan research network that provides reliable, nationally representative survey data on Africans’ experiences and evaluations of democracy, governance, and quality of life.

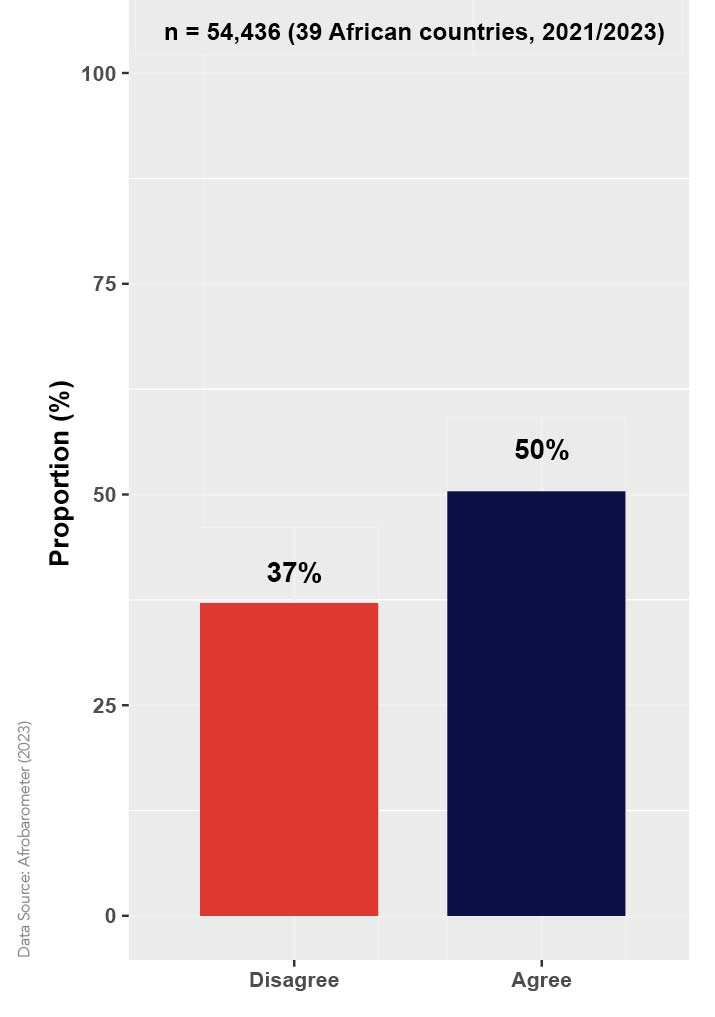

In my analysis, I focused on Afrobarometer question 73b, which asked a sample of 54,436 Africans whether they agree or disagree with the following statement: Ordinary citizens currently have a voice in decisions about natural resource extraction that takes place near their communities.

The respondents chose from the following options: “Strongly disagree,” “Disagree,” “Neither agree nor disagree,” “Agree,” “Strongly agree,” “Refused,” and “Don’t know.” For the analysis, I combined “Strongly agree” and “Agree” into a single “Agree” category and similarly grouped “Strongly disagree” with “Disagree” into “Disagree.” I excluded the remaining 13% of responses.

My first aim was to understand how much respondents feel ordinary citizens have a voice in decisions about natural resource extraction that takes place near their communities.

Figure 1 shows that a little over half (approximately 50%) of respondents said ordinary citizens have a voice in natural resource governance and extraction near them, while 37% feel ordinary citizens are excluded. The latter highlights the exclusionary nature of some African countries, especially autocratic ones, where the voices of ordinary people, especially in rural areas, are often ignored in key policy issues in favour of elites and multinational corporations.

In Figure 2, I wanted to understand how these responses varied based on the latest V-Dem ranking of the countries on liberal democracy. I grouped the 54,436 Afrobarometer respondents from 39 African countries into four quartiles according to their country’s latest liberal democracy scores and took the average of responses in each quartile.

The error bars represent the standard error – this quantifies how much the mean citizen involvement in each liberal democracy group might vary if different samples were drawn from the same population. The small error bars suggest more precise estimates and greater confidence in the mean values.

From the figure, we can see how moving from the lowest-performing to top-performing groups on liberal democracy corresponds with increased reported involvement of ordinary citizens in natural resource governance. This distinction is more pronounced when comparing the upper half of countries on liberal democracy with the lowest-performing group (bottom 25%). Specifically, the average reported involvement of ordinary citizens in natural resource governance among the top 50% of countries in liberal democracy is 19% higher than that observed in the bottom 25%.

In essence, on average, ordinary citizens’ participation in natural resource decisions is higher in more democratic African countries than in less democratic ones. This finding remained consistent after controlling for two potentially confounding factors using regression analysis – GDP per capita (which measures economic size) and the population size of those countries in 2022.

The results suggest that democracy enables ordinary Africans to engage with natural resource decision-making that affects them and their communities. Thus, when institutions are transparent and accountable and when the rule of law prevails (key ideals of democracy), it creates avenues for community input through public consultations, local councils, or civil society organisations. This pattern emerges despite the many defects of real-world democracies in Africa.

The finding also suggests that strengthening democratic institutions could lead to more inclusive decision-making processes about natural resources. In other words, African countries can ensure that natural resource policies and practices are people-driven by embracing democratic ideals.

This is more so for African countries with weaker democratic structures, where the data shows that ordinary citizens are less likely to have a voice in decisions about natural resource extraction that takes place near their communities. In such countries, it becomes vital to create an enabling environment for citizen participation, building trust between the government and its people, and thus reducing the likelihood of resource-based conflicts, among others.

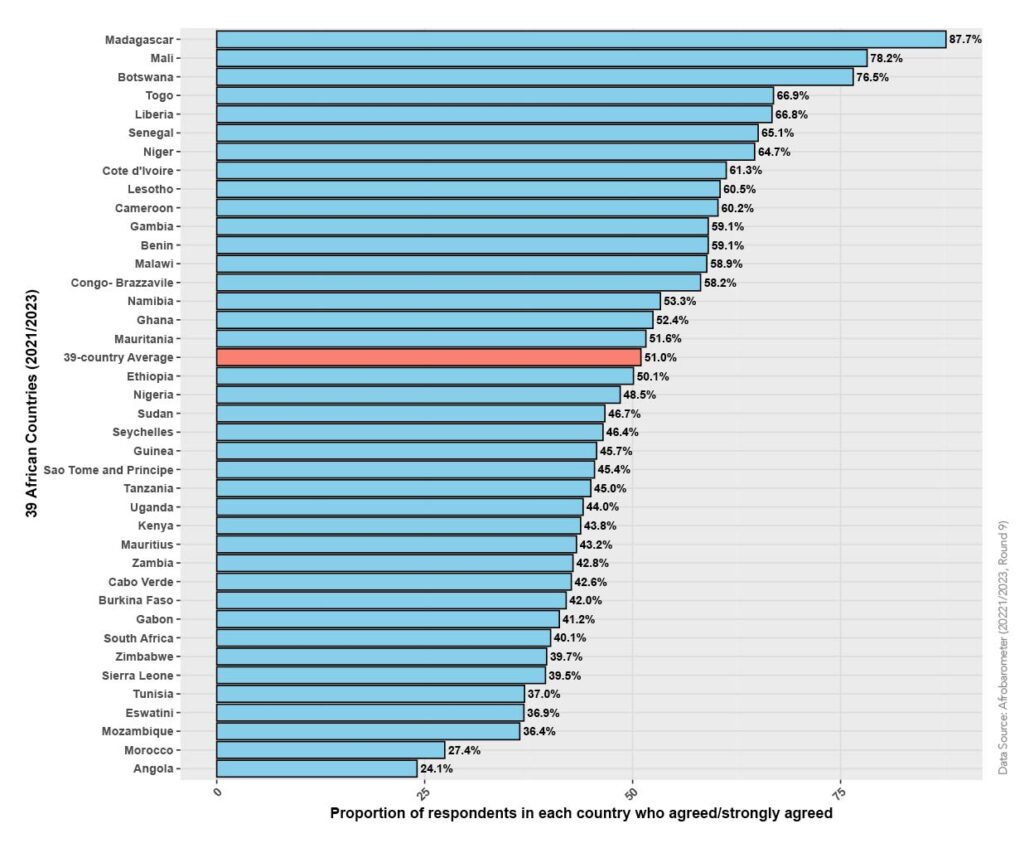

In Figure 3, I unpacked the variations in responses on citizen involvement across the 39 African countries surveyed by Afrobarometer.

Figure 3 shows wide variation at the country level in responses on whether ordinary citizens have a voice in decisions about natural resource extraction that takes place near their communities. Out of the 39 African countries, only 17 (less than half) surpassed the 39-country average of 51% for citizen involvement in natural resource governance, while 22 countries fell below average. This indicates a lower proportion of respondents in these 22 countries who say that ordinary citizens have a voice in natural resource extraction decisions compared to the average.

Precisely, in less democratic countries, such as Angola and Eswatini, respondents were less likely to say that ordinary citizens have a voice in natural resource decisions compared to more democratic countries like Senegal and Botswana, where citizens are more likely to have a voice.

To better illustrate the results, imagine natural resources as a garden, with soil richness differing from plot to plot. In Angola, the soil is fertile with oil and diamonds, resources that could transform the lives of millions if properly managed. However, in this analogy, the garden is fenced off, with Angola’s government acting as a gatekeeper. The citizens, standing outside the fence, can see the resources being extracted, but they have no say in how the land is worked or how the wealth is distributed. Angola’s oil, for example, generates billions, but much of that wealth is captured by elites, while the communities living near oil fields face environmental destruction and poverty. In this closed system, where democracy is limited, the citizens have little influence on decisions about the land they commonly own and rely on.

Eswatini, though not as resource-rich as Angola, is home to timber, sugar, and minerals. Yet, the kingdom operates in much the same way – citizens have little control over how these resources are managed. The monarchy holds the keys to the garden, dictating how its resources are utilised while citizens watch decisions being made from afar, with no opportunity to participate or voice their concerns about the sustainability of the land or the fairness of the harvest. In both Angola and Eswatini, the closed nature of governance means that the garden, though abundant, primarily serves the interests of a select few while ordinary people remain on the outside.

Contrast this with Botswana’s diamond-rich soil, where the garden is managed more collectively. Here, the gate is open, and the garden is more welcoming. Botswana’s democratic system allows citizens and other stakeholders (e.g., civil society and local leaders) to have a say in how the diamonds are extracted and how the wealth is reinvested into the community – e.g., through healthcare, education, and infrastructure, ensuring that harvest is shared more equitably.

Similarly, in Senegal, where the garden contains fisheries and mineral deposits, the government works more collaboratively with citizens and local communities. The country’s democracy allows fishermen, community leaders, and civil society groups to have a voice in decisions about how these resources are managed. This inclusivity protects the environment from over-extraction and ensures that the wealth generated from these resources is reinvested in ways that benefit the broader population.

In open, democratic systems, decisions are more inclusive and collective, which may lead to more sustainable and equitable outcomes. In resource-rich ones, democracy means the resource wealth can be equitably shared since the soil is rich, and governance structures encourage participation. Citizens have a voice, which ensures that resource wealth benefits many rather than a few. In less democratic countries, the garden is fenced off, with wealth concentrated in the hands of a few and the voices of ordinary citizens stifled.

Taken together, the data highlights how democracy enables inclusive natural resource governance and conservation. While just over half of Africans say that ordinary citizens have a voice in natural resource governance, this varies based on how democratic African countries are. Citizen involvement is higher in more democratic African countries than in less democratic ones. Despite the many shortcomings of democratic governance, African democracies still outperform their less democratic counterparts in fostering inclusive natural resource governance.

Nnaemeka is a Senior Data Analyst at Good Governance Africa. He holds a Master’s degree in e-Science (Data Science) from the University of the Witwatersrand, funded by South Africa’s Department of Science and Innovation. Much of his research explores socio-political issues like human development, governance, bias, and disinformation, using data science. He has published research in scholarly journals like EPJ Data Science, Politeia, the Journal of Social Development in Africa, and The Africa Governance Papers. He has experience working as a Data Consultant at DataEQ Consulting. He has also taught at the Federal University, Lafia (Nigeria) and the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg (South Africa).