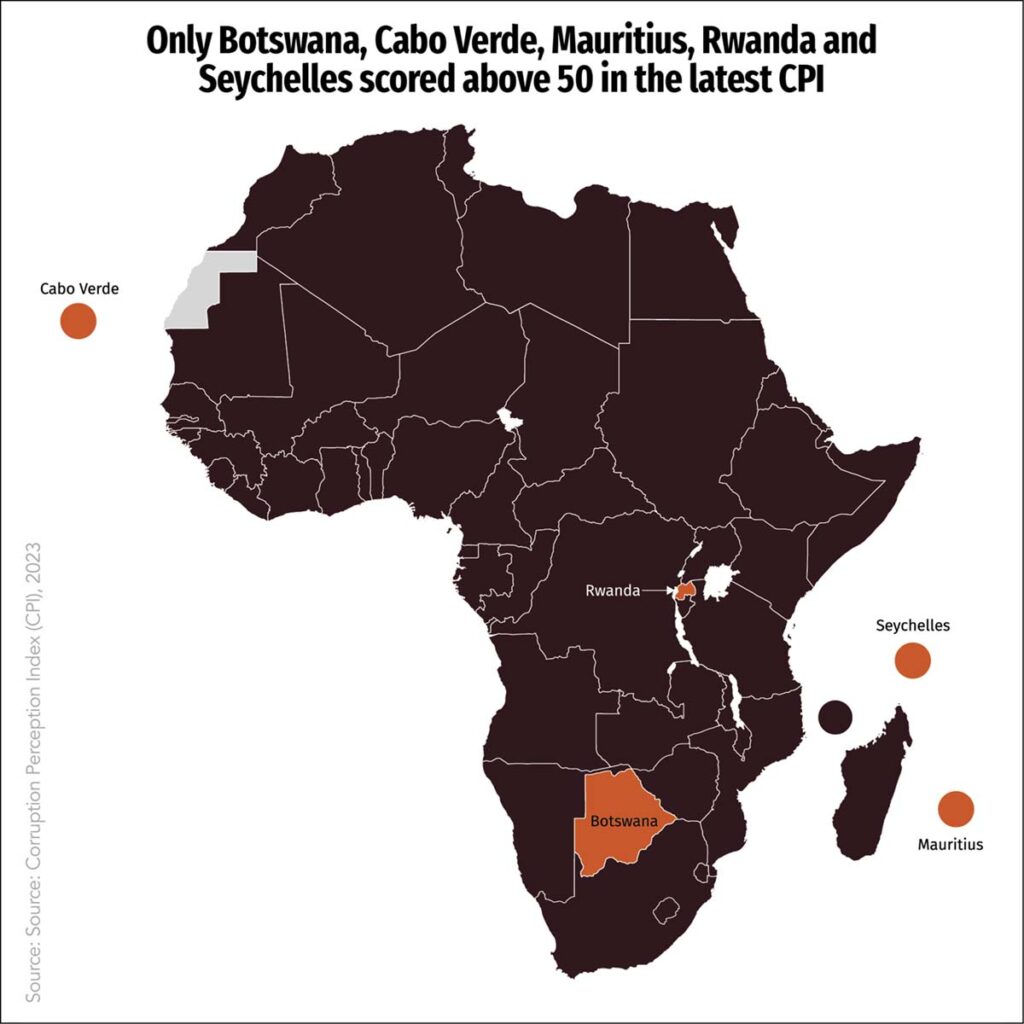

New data from Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index shows that 90%, or 49 out of 54 countries in Africa, scored under 50/100 in 2023 (CPI, 2024). Moreover, the regional average score for sub-Saharan Africa was an underwhelming 32/100, and revealed a worrying trend [Figure 1].

Against this background, what is the impact of high levels of corruption on the continent? How are corruption trends and governments’ performance in fighting corruption perceived by experts and investors? And to what extent do ordinary citizens engage with or feel safe to report corruption when they encounter it?

Corruption, whether in the public or private sector, can be understood as activities that involve individuals misusing their positions for personal and private gain, at the expense of their duties or public interest. It can manifest as either petty or grand corruption, encompassing bribery, embezzlement, nepotism, and more. These issues are particularly destructive in nations with weak institutions and regulatory mechanisms, diverting crucial resources from essential public services needed for sustainable development.

In Kenya, it is estimated that 8% of government revenue, or around $1 billion, is lost annually to trade mis-invoicing from illicit financial flows (IFF) activity. Elsewhere, in Nigeria, around 4% of total government revenue, equivalent to $2.2 billion, is lost. In Malawi, according to a 2020 paper by Kemp Ronald Hope, an estimated 13-17% of GDP is reportedly lost to corruption and tax fraud.

In Tanzania, corruption accounts for 20% annually of national budget leakage and roughly $1.8 billion, when combined with tax revenue losses from IFFs. In Madagascar, meanwhile, it is estimated that as much as 40% of the country’s budget is lost to corruption. In South Africa, losses to corruption are estimated at around $7.4 billion from trade mis-invoicing alone as an IFF activity.

For context, the average African would need about 265 years to earn a billion dollars, based on the average income of around $3,772 in 2020 for sub-Saharan Africa, according to World Bank data for that year. These financial leakages indicate the corrosive and detrimental impact of corruption on economic growth and development on the continent and highlight how fraudulent activity perpetuates poverty and inequality.

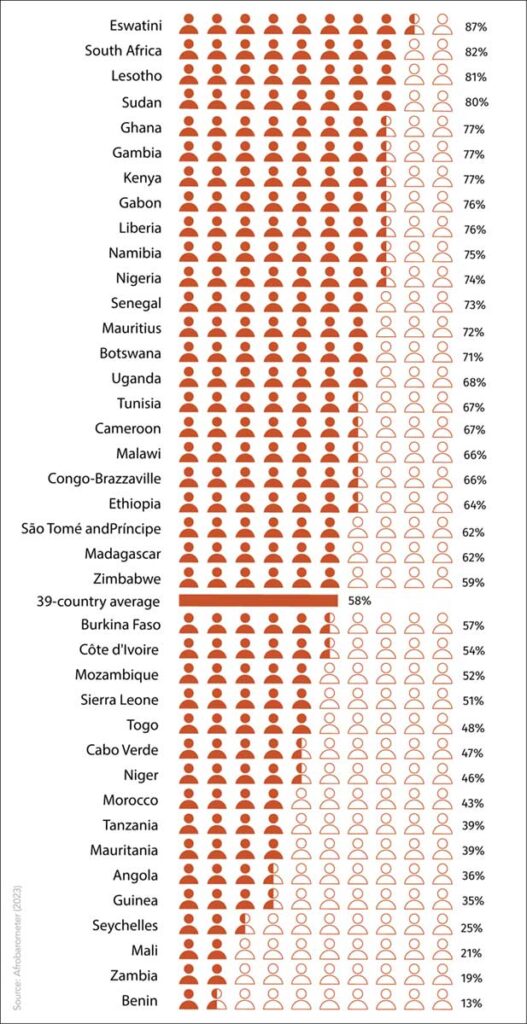

The latest Afrobarometer survey of more than 39 countries reveals that in the eyes of many ordinary Africans, there’s a growing concern that corruption is on the rise. According to the survey, over half (or 58%) of citizens on average feel that corruption levels in their nation either increased or worsened to some extent between 2021 and 2023 with little improvement in governmental efforts to combat it [Figure 2].

Among the various activities that fall under the umbrella term “corruption”, some are particularly pervasive across the continent. The first is money laundering and IFFs. These, effectively, are activities that syphon large sums of money intended for public or private use into personal or individual hands by making use of off-shore accounts and bypassing law enforcement and regulatory bodies.

The next is what has become known as “state capture”. This involves an unethical entanglement of powerful business people and state officials in which public institutions are subverted for private gain. This form of corruption can be particularly destructive because, according to Hope, it results in an “economy [that] becomes trapped in a vicious state in which the policy and institutional reforms necessary to improve governance are undermined by collusion between powerful firms and state officials who extract substantial private gains from the absence of a clear rule of law”. The most notorious and recent incidence of state capture in Africa was the activities of South Africa’s former president Jacob Zuma and other members of the ruling elite, along with the Gupta family, between 2009 and 2018.

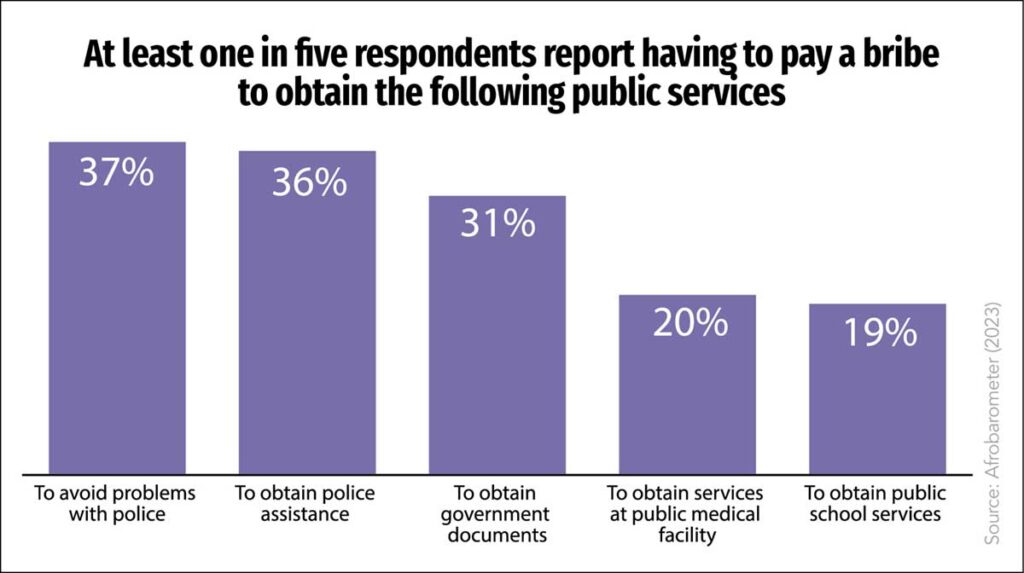

Yet despite the pervasiveness of these “grand” forms of corruption that often involve high-profile figures and public officials, more insidious, everyday, systemic forms of corruption continue to affect ordinary Africans, largely with low accountability. When ordinary citizens were asked to evaluate the involvement of various public officials, the police consistently ranked highest in perceptions of widespread graft [Figure 3]. Across 39 countries, nearly half (46%) of citizens believed that “most” or “all” police officials were corrupt, ranking them above tax officials, officials in the presidency, civil servants, parliament and business executives – Gabon, South Africa, Nigeria, Liberia, and Uganda stood out with some of the highest perceived levels of official corruption.

The report further revealed that a significant portion of citizens reported having to pay bribes or kickbacks, predominantly to avoid further issues with, or attain assistance from, the police to obtain government documents, services at medical facilities or generally access basic public services. Within this there was a pervasive fear of reprisal for reporting corruption to the authorities, revealing how individuals may be pressured to engage in corruption enabled by state officials amid a broader culture of normalisation. The other issue with bribes and kickbacks is that though they may “grease the wheels” of bureaucracy they also corrode the integrity of public service.

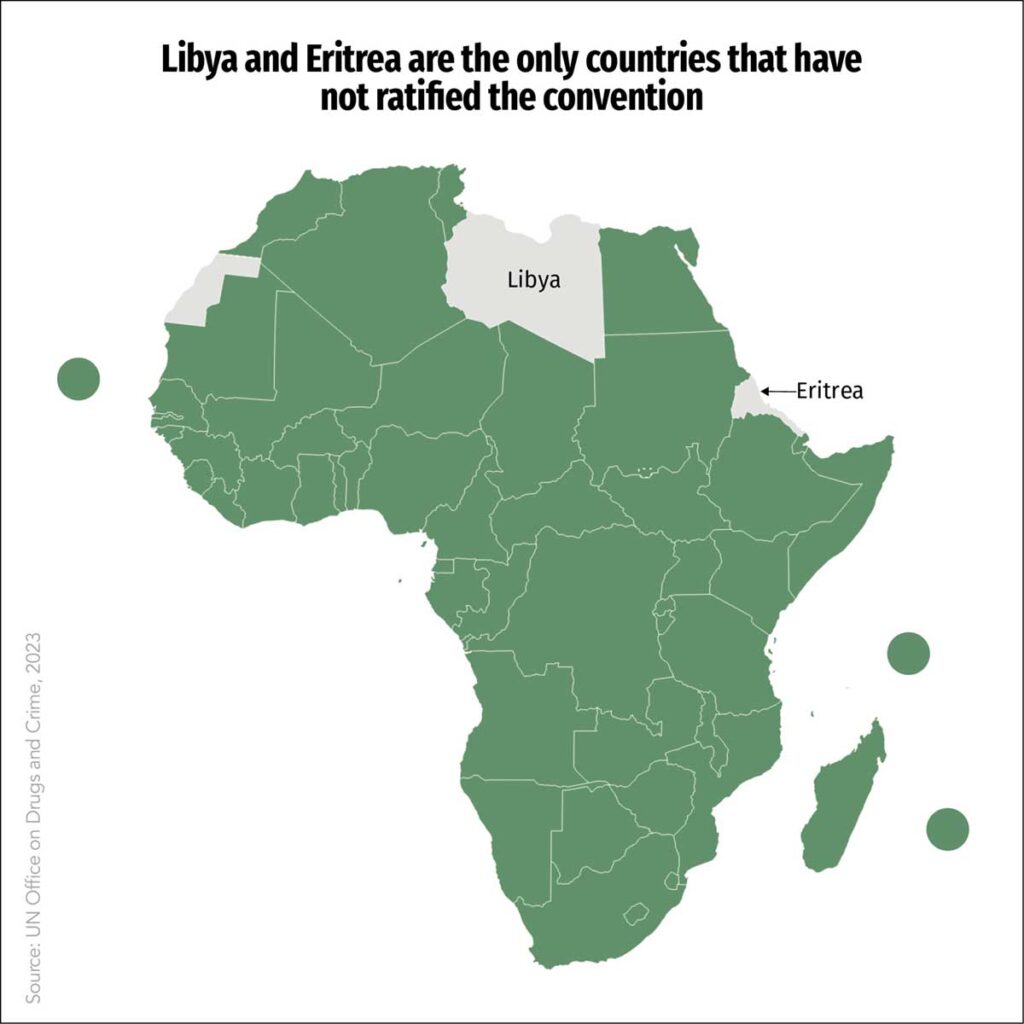

All this is not to say that African countries are making no effort to regulate corruption. In an attempt to address the prevalence and impact of corruption, many African countries have ratified and agreed to several conventions, frameworks or initiatives, including; the 2003 United Nations Convention Against Corruption (UNCAC) signed by all African states, excluding Eritrea and Libya [Figure 4]. The African Union Convention on Preventing and Combating Corruption was signed by all states except Benin, Central African Republic, Cabo Verde, Malawi, Morocco and Seychelles. Also in place is the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI), in which extractive-heavy nations commit to stronger, more transparent and accountable extractive sectors to the EITI Standard of which 28 African countries are currently part.

However, despite these anti-corruption commitments, political buy-in remains low and implementation is often ineffective, yielding inadequate results – ultimately reinforcing the sentiment among citizens that corruption within key institutions is rampant.

Moreover, whistleblowing and flagging anti-corruption for ordinary Africans, as well as key civil society organisations, often comes at a high cost. In South Africa, whistle-blower Babita Deokaran was murdered after flagging corrupt activity in the Gauteng Health Department in August 2021 and represents one of many who lost their lives in fighting corruption.

Elsewhere, in the Democratic Republic of Congo, diamond businessman Dan Gertler has filed a defamation lawsuit against 146 civil society organisations that form the country’s leading anti-corruption coalition, Congo is Not for Sale (CNPAV). The lawsuit targets spokespersons Jean-Claude Mputu and Resource Matters and stems from an interview Mputu gave disclosing Gertler’s allegedly fraudulent company earnings in the DRC. Despite evidence supporting CNPAV’s claims, Gertler seeks one million Euros in damages. The case in DRC reflects a broader, more worrying trend against anti-corruption activists, whistle-blowers, journalists, and civil society groups and sheds light on systemic challenges that confront anti-corruption work.

As corruption continues to corrode the governance efficacy and institutional structures of African nations, it ultimately obstructs the provision of essential public services such as water, sanitation, education, and healthcare. It also impedes the development of critical infrastructure such as electricity and roads while driving up investment costs, inevitably diminishing sustainable and ethical investment flows crucial for job creation and trade.

From facilitating business deals to securing favourable regulatory decisions, the pervasive culture of corruption undermines fair competition and stifles economic growth. As African countries grapple with the multifaceted, systematically embedded challenges presented by corruption, addressing these entrenched issues requires a concerted effort and commitment from both domestic stakeholders and the international community. Without more decisive action to tackle it at its roots and promote transparency and accountability, the aspirations of African nations for sustainable development and prosperity will remain elusive.

Mischka Moosa is a data journalist at GGA. She holds a Bachelor of Social Science with majors in Gender Studies and Political Science that she obtained from the University of Cape Town. Her focus of interest is on decolonial approaches to justice, development and transformation in Africa.