The impact of disinformation legislation on freedom of speech

In recent years, Africa’s digital landscape has rapidly evolved. Between 2017 and 2024, 300 million Africans came online and gained access to the internet and social media, according to an Africa Center for Strategic Studies (ACSS) report this year. With millions more Africans now connected to the digital world, the landscape of information dissemination on the continent has significantly altered; on one hand creating new avenues for communication, while on the other, it has exposed critical issues around the challenges posed by disinformation.

Disinformation is understood as the deliberate dissemination of false or misleading information with the intention of exploiting or disrupting information networks to negatively influence public opinion. It becomes harmful because it often threatens political stability, erodes public trust in democratic institutions and undermines the principles of a free society. As the ACSS noted, “disinformation campaigns have directly driven deadly violence, promoted and validated military coups, cowed civil society members into silence, and served as smokescreens for corruption and exploitation”.

Disinformation efforts have targeted every region on the continent. ACSS data revealed that at least 39 African countries have been the target of specific disinformation campaigns that sought to trigger destabilising and anti-democratic effects across African information systems. As a result, efforts to combat disinformation have significantly intensified as governments attempt to mitigate the spread of disinformation through legislation.

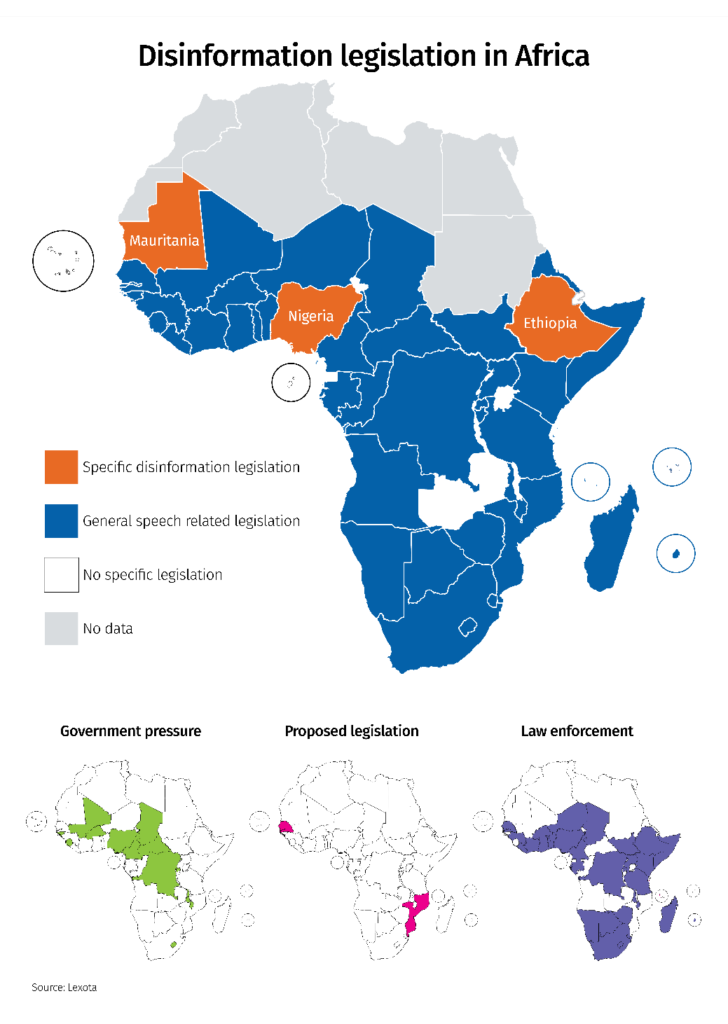

Several African countries have imposed various legislative approaches to curb the spread of disinformation. Figure 1 highlights the various ways that governments have tried to address the problem. This includes specific anti-disinformation legislation (orange on map), general speech (blue on map), law enforcement action (purple on map), government pressure (green on map), and proposed legislation (pink on map).

In sub-Saharan Africa, the majority (42) of countries have imposed some general speech legislation, the scope of which does not specifically target disinformation but refers instead to broader legal frameworks related to general media laws, cybercrime, or others. Examples include the Electoral Act, 1998 in South Africa or the Electronic Communications Act, 2008 (Act 775) in Ghana.

Law enforcement action extends to arrests, investigations, or other measures brought by the state against individuals or organisations accused of spreading disinformation. Government pressure, meanwhile, refers to state actions not grounded in law but intended to regulate how information is disseminated and controlled.

Lastly, specific and proposed legislation refers to legislation that directly seeks to combat false information spread intentionally to deceive people. Only three African countries – Ethiopia, Mauritania, and Nigeria – have imposed specific disinformation legislation.

However, the use of specific legislation to combat disinformation has raised questions about its limitations on fundamental democratic freedoms such as speech and expression. Researchers have argued that due to the complexity of disinformation, very specific legislation is difficult to implement without infringing on various human rights related to speech and expression. While these freedoms are not absolute, there has been rising concern that legislation like this is being used to repress journalists, activists, and government critics.

This raises the interesting question of whether legislation is a useful approach to combating disinformation or if it opens doors for governments to misuse and undermine the democratic system.

Nigeria has one of the most developed legal frameworks for directly combating disinformation. Three key pieces of legislation (the Criminal Code Act of 1990, the Cybercrimes Act of 2015, and the draft Code of Practice for Computer Service Platforms and Internet Intermediaries of 2022) address disinformation specifically, with other laws complementing them.

Older laws, such as the Criminal Code Act of 1990, have roots in the country’s former military dictatorship, while Nigeria’s more recent legislation has largely arisen due to security concerns. According to the 2024 ACSS study, Nigeria has seen several disinformation campaigns originating with domestic extremist groups such as Boko Haram. These campaigns exacerbate security risks for the state, add to the current challenges posed by extremist groups, and deepen social divides by promoting hate speech.

However, human rights groups have highlighted the limitations of these various pieces of legislation, arguing they are vague in definition. For example, the 2022 legislation around internet practice does not define “prohibited content”, enabling the law to be misused against journalists or members of the public who are critical of the government.

Questions have been raised about the proportionality between the crime and the punishment. Punitive punishment methods such as harassment or detention, summary executions or media bans for the dissemination of false information have been widely criticised, and the government has used the legislation to repress government critics according to Amnesty International 2022).

Ethiopia enacted the Hate Speech and Disinformation Prevention and Suppression Proclamation in 2020. This piece of legislation focuses on disinformation more generally and strongly emphasises disinformation in relation to hate speech.

This legislation was first introduced in the context of a wider democratic transition that took place between 2017 and 2018, when the dynamics of the country’s ruling coalition shifted, and a new prime minister was elected. Before this, disinformation campaigns had been used to heighten social tensions and amplify violence against various ethnic and religious groups. As such, this legislation focused on preventing hate speech but also made provision for disinformation in general.

Civil society groups have heavily criticised the bill for several reasons, including the vague definition of fake information, which enables authorities to interpret it in ways that undermine a number of democratic freedoms, and its punitive approach. As an Associate Professor at Addis Ababa University School of Law, Girmachew Alemu Aneme has argued that the law relies on punishment as opposed to literacy to address the dissemination of disinformation.

Thus, while the legislation can be used to prevent the dissemination of false and fake information, Ethiopia has one of the highest arrest rates of journalists in sub-Saharan Africa, leading to concerns about the law’s potential to undermine freedom of speech, especially for those criticising the government.

Unlike Nigeria and Ethiopia, both of whom introduced legislation amidst security issues, Mauritania introduced Law No. 2020-015 to fight the manipulation of information and address the surge of misinformation around COVID-19. The pandemic saw a huge wave of disinformation, making it difficult for governments to respond effectively.

While the law was mainly intended for public health emergencies and elections, it has the potential for wider application. Mauritania also has a history of media censorship and the repression of journalists. So, massive reforms to improve freedom of the press have been implemented, but the bill remains vulnerable to misuse. This is because its penalties are not explicitly related to the harm caused or the intent to harm, resulting in the possibility of enactment even where individuals unknowingly spread false information.

Thus, while Nigeria, Ethiopia and Mauritania have enacted specific legislation relating to disinformation, a concerning trend of using these laws to repress dissent and criticism of the government has emerged. So, what does this tell us about the role of specific legislation around disinformation and its ability to combat it?

The research suggests that specific disinformation legislation is often misused despite differing contexts and complex factors, offering two key insights.

First, in each of these three countries, the laws lack specificity within the legislation itself. As mentioned, Nigeria and Ethiopia have vague definitions of key terms, which leaves plenty of room for interpretation. This lack of clarity, in many cases, benefits the state and allows greater room for the legislation to be misused. To avoid this, governments should enable the public to provide comments and feedback on proposed bills, encouraging greater clarity and addressing overlooked issues.

Second, using punitive punishment to address disinformation issues is problematic. While in some cases, this might be appropriate, it also risks undermining efforts to combat widespread disinformation. In many cases, the problem arises from people’s inability to identify fake news rather than the intentional spreading of such information. Punitive punishment also creates a dangerous precedent, which, as with the vagueness of language, can undermine democratic values and freedoms.

So, while legislation is important for addressing disinformation, it is often muddled by issues that undermine other democratic processes. Looking at the three countries used as examples here and which have specific legislation around disinformation, it’s clear that the complexity involved requires time and the input of various stakeholders. Also, while legislation should be one of the key building blocks, combating disinformation requires more than just punishment; it requires active civic engagement and education.