Home to many of the large animals left in Africa, few countries have attracted as much conservation interest as Tanzania. Land has often been protected at the expense of human populations, who used to live in conservation areas, but the government says that local communities are now consulted much more widely than in the past. Yet the track record of Tanzania’s inclusive conservation efforts varies enormously.

There is no doubt that conservation efforts are particularly needed in Tanzania. The country is home to a wide range of globally important habitats, from the savannah of popular tourist imagination in the Serengeti to coral reef ecosystems offshore. The Tanzania National Parks Authority manages 22 parks that cover 99,306 sq km of the country’s 945,087 sq km territory. Moreover, 28% of the country’s total land area comprises a variety of protected wildlife areas, with another 16% in forest reserves, according to a US Congressional Research Service report from July last year.

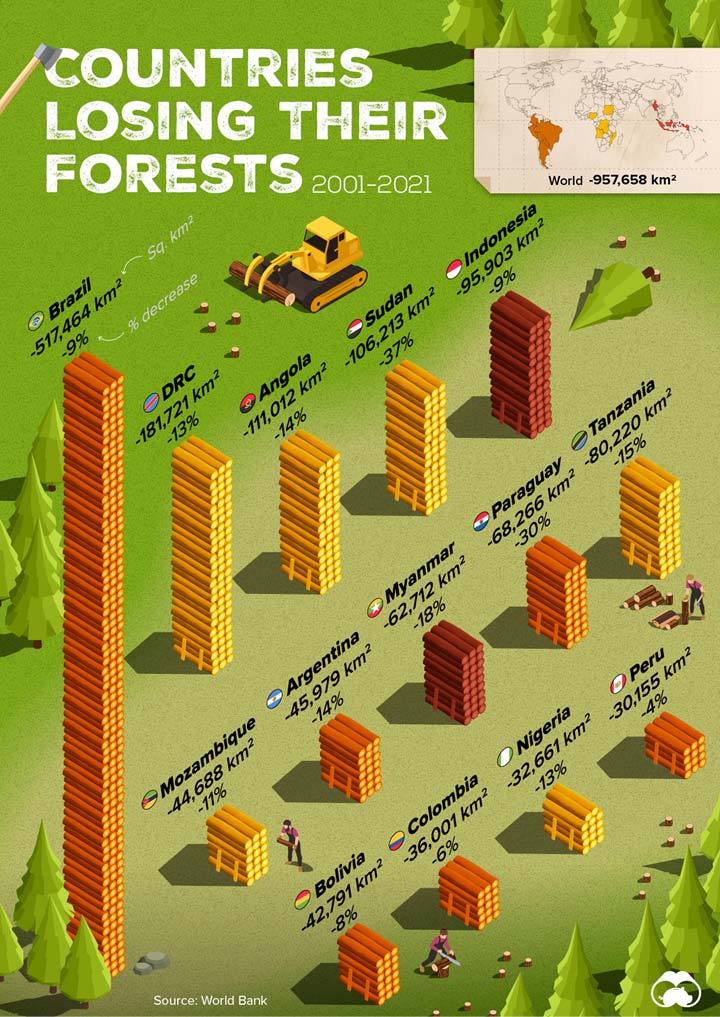

Yet a combination of poaching, population growth, agriculture and deforestation has had a huge impact on delicate ecosystems. While the World Bank calculates that 51% of the country was forested to some extent in 2021, Global Forest Watch reports that the country lost 12% of its tree cover between 2001 and 2023.

For example, the elephant population crashed from 316,000 in 1976 to 43,000 in 2014, although it had recovered to 60,000 by 2021 due to tougher action on poachers. The country still has the third-biggest elephant population in Africa, but declines elsewhere have been even more dramatic. The total number of elephants in Africa fell from about 10 million in 1930 to 415,000 today, according to the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF).

Apart from the obvious benefits of biodiversity, preserving the natural world drives one of Tanzania’s main sources of income. A total of 1.8 million tourists visited the country in 2023, the most ever, and a 24.3% increase on the previous year, generating a GDP of $3.4 billion in the process. Yet visitors are often sold a vision of an African wilderness devoid of people that is at odds with historical reality.

Most wildlife tourists visit the northern park circuit, which includes the Serengeti, Ngorongoro Crater, and Lake Manyara. Various ethnic groups live or have lived here until relatively recently, and interactions with the Maasai are often sold as part of tourist packages.

However, the Tanzanian authorities have steadily sought to remove such communities. Given the effect of global poaching networks and increasing firewood collection, such a strategy is, to some extent, understandable. However, the devastating human cost of such strategies is now being challenged worldwide. Inclusive conservation began as simply ensuring that local communities benefited from conservation efforts, with people in and around Tanzanian parks gaining employment as guides, drivers, cooks and in lodges, for example. Some safari tour operators also supported school, healthcare and other development projects in return for community buy-in to safari operations.

Local people were also able to set up tourist accommodation outside protected areas. However, the latter has not happened as often as might be expected, with foreign firms or companies based elsewhere in the host country usually having more money to provide tourist accommodation.

All too often, such strategies were seen as simply buying off local communities. As a result, the best inclusive conservation schemes have now become more nuanced, with local people involved in decision making as well as through employment and sustainable forest management rights.

One positive Tanzanian example comes from the other main centre of Tanzanian tourism, on the island of Unguja, which is part of Zanzibar. The Zanzibar red colobus monkey is only found on Unguja and principally in the island’s main onshore conservation area, Jozani-Chwaka Bay National Park. However, efforts to protect them were hindered by the local perception of the monkeys as pests. Many were killed for feeding on banana and cassava crops.

But attitudes changed when communities bordering Jozani were given a real stake in the park’s success in terms of employment and local people becoming shareholders in the conservation project. Jozani-Chwaka Bay Conservation Project, as it was then called, was created jointly by the Zanzibar Department of Commercial Crops, Fruits and Forestry (DCCFF) and CARE Tanzania in 1995. Local communities received half of all revenue generated from 2008 onwards, with some paid as compensation for damaged crops and the rest invested in local schools, roads, water supplies and power connections. Disagreements over compensation levels continue, but the project is broadly considered a success, with the red colobus population increasing from fewer than 2,000 in the 1990s to more than 5,000 now and attracting 60,000 visitors a year.

CARE International, which works with local NGOs at Jozani, hopes to expand the size of the park and is considering selling carbon credits to raise more income. There are various mechanisms for achieving this, including the UN’s REDD+ (Reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation in developing countries) framework that encourages developing countries to conserve forests as carbon sinks in return for financing. However, in high profile media investigations, including by the UK’s Guardian newspaper, some REDD+ projects have been criticised for the lack of community benefit and exaggerated claims over forest sizes. The biggest example is the Kariba project in Zimbabwe, where carbon offset developer South Pole pulled out in October 2023 because of concerns that the money was not going to local people and the forest wasn’t as big as claimed.

As the WWF argued in a February 2024 report, “Meaningfully engaging with local communities means working with communities…from planning and design to implementation and monitoring. While conservation practitioners often understand the value of this holistic approach, it can be challenging to find the necessary funding for these kinds of projects.”

The WWF said it was committed to inclusive conservation, arguing that “the most successful conservation projects are those that partner with local communities who derive benefits from the ecosystems they steward”, although it conceded this was a difficult process.

Tanzania struggles with the same debate as the rest of the world: Should we focus on ringfencing specific areas where habitats, flora, and fauna are protected, and people excluded, or seek to promote the sustainable integration of human populations within a healthy natural world? The former often means displacing people and can leave relatively vulnerable species of plants and animals isolated from each other in fenced-off areas.

However, seeking to retain or create untouched wilderness can also conserve threatened species in the long-term, perhaps for a time when we are better placed to integrate human activity within the natural world when human populations begin to fall. Such concerns are particularly acute in Tanzania, where the human population increased from just 10.9 million at independence in 1963 to an estimated 69.1 million in 2024, with the UN predicting a population of 304 million in 2100.

Any resettlement must be undertaken compassionately, and this has clearly not been the case in northern Tanzania, where the Maasai have long been subject to marginalisation and discrimination. Human Rights Watch (HRW) reported in July last year that the Tanzanian government aims to relocate 82,000 Maasai from the Ngorongoro Conservation Area and surrounding areas by 2027 for “conservation and tourism purposes”.

The government claims that it has consulted local people over the process to take their needs into account, but HRW said that people had been forcibly evicted from their homes, and farming and grazing were banned over large areas. Since June 2022, resettlement enforcement has included “beatings, shootings, sexual violence and arbitrary arrests to forcibly evict residents from their land”, according to HRW.

Maasai groups have also lost access to religious and cultural sites. At the same time, government conservation efforts are “disrupting their traditional way of life and severing their connection to the land”. Juliana Nnoko, HRW senior researcher, Women’s Rights Division, said in August last year. These moves are even more difficult to accept when they are designed to make way for trophy hunting, a long-running sore spot between Tanzania and neighbouring Kenya, which banned the practice in 1977.

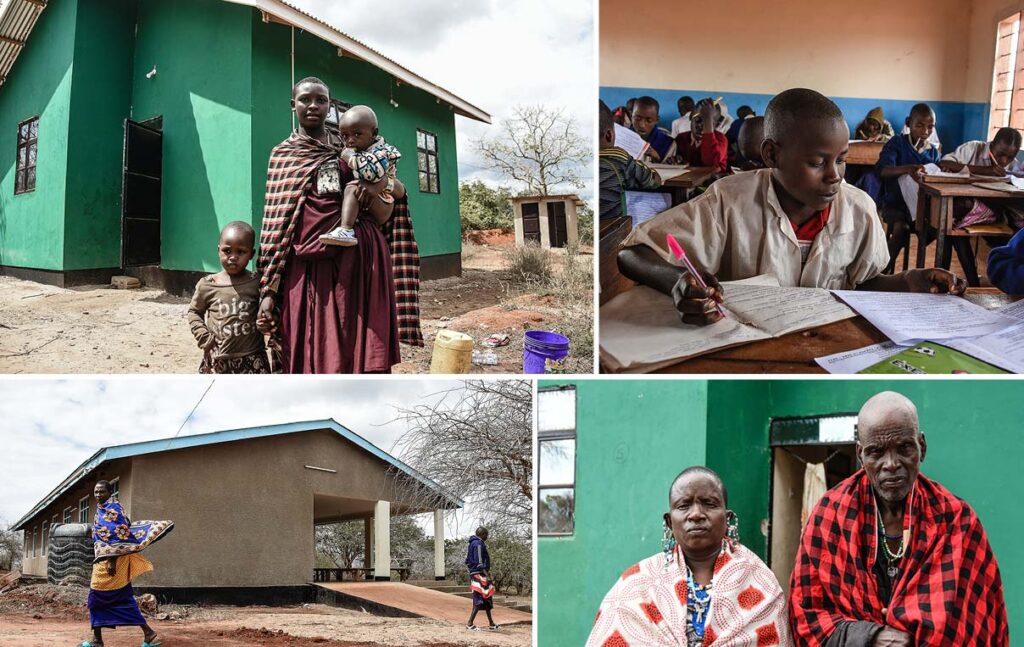

HRW found one resettlement village, Msomera, in the Tanga region, which is 600 km from the new inhabitants’ original homes. The resettled Maasai have access to piped water, electricity and a school, but HRW argues that the voluntary resettlement programme is far from voluntary, while the new houses are unfit for Maasai traditional multi-generational households. The original inhabitants of Msomera have also lost some of their land in the process.

In June 2024, the European Union cancelled €18.4 million in conservation funding for Tanzania because of the treatment of Maasai in the Ngorongoro and Loliondo areas. It called on the Tanzanian government to stop funding conservation projects that violate human rights. Two months earlier, the World Bank also suspended the final $50 million tranche of its $150 million funding for the expansion of Ruaha National Park in southern Tanzania because of human rights abuses.

Even where there is some consultation over relocation, “women are given a subordinate role in what little decision-making occurs,” said Nnoko. Displaced pregnant women have had to choose between living close to family members or health services because only men tend to be consulted, she added.

The reports surrounding the relocation of Maasai in northern Tanzania are obviously shocking and require full investigation. Yet more widely, it is clear that the inclusive conservation being pursued is far from inclusive. The process requires the full involvement of local communities of all ethnic groups and genders, including in leadership roles. Apart from anything else, local people have a lot of useful knowledge, including on long-term environmental changes.

In addition, the jobs on offer tend to be given to fairly narrow sections of the population, in terms of gender but sometimes also ethnicity. Local populations vary enormously in terms of culture, lifestyle and attitudes. Tanzania has a particularly wide range of ethnic identities and cultures, with the hunter-gatherer Hadza and pastoralist Maasai having very different perspectives on land use from the many farming communities that live around the northern Tanzanian parks. At the same time, there should be no expectation that any ethnic group will stick to traditional activities without the option of change.

The only way to ensure that local people are included in conservation efforts is to consult widely and include a wide range of different interests in decision-making bodies. Tourists also need to be educated away from perceptions of pristine natural environments empty of all humans. Only then can there be a long-term future for flourishing habitats and wildlife alongside human development in what is one of the most biodiverse places on earth.

Dr Neil Alexander Ford has been a freelance consultant and journalist on African affairs for more than two decades. He covers a wide range of topics from international relations and organised crime to cross-border trade and renewable energy. Consultancy clients include international organisations, law firms and financial services companies, and he has acted as an expert witness in Africa-related legal cases. He has a PhD on East Africa’s international boundaries, ranging over the effect on regional economies; cross-border political disputes; and the impact of the boundaries on local communities, such as the Maasai.