In a fascinating book, Biblical Critical Theory, Christopher Watkin demonstrates how the Christian Bible’s salient moments cut through much of the reductionism evident along the political spectrum today. An early insight is how humanity has lost its way when it comes to our treatment of the natural world. The “marketisation of everything” has led to a cold divide that divorces us from the wonder and intrinsic beauty of nature. Whether you’re on the left and calling for “environmental justice” or on the right, calling for nature to be “valued” in neoclassical economic terms, you might want to consider that there is another way to view things.

In this polarised world, the debate about what an optimal approach to conservation looks like is highly divisive. The left calls for the demolition of neoclassical economics and its propensity to turn nature into a commodity. The right calls for the privatisation of wildlife as the only means of protecting endangered species. We need to think about how we got here and how we can plausibly navigate our way out of this impasse.

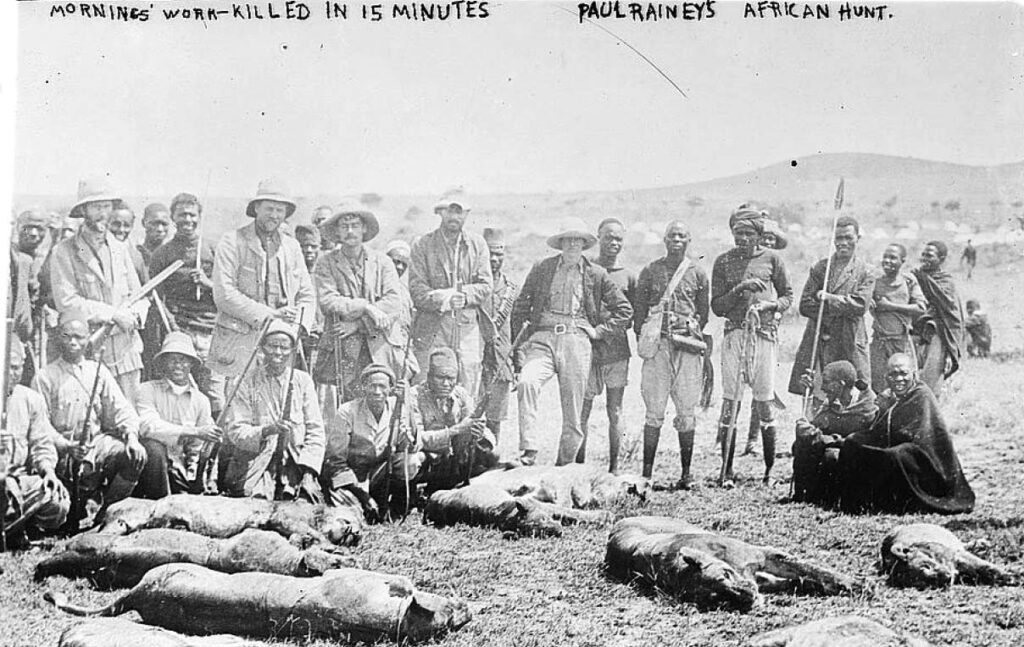

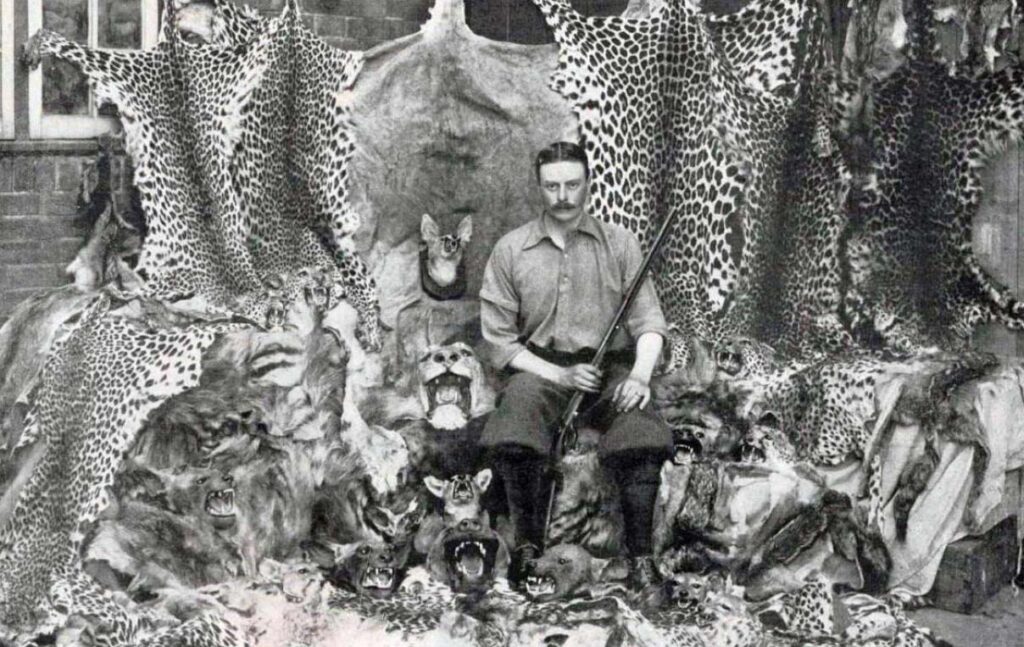

Across African contexts, it is helpful to understand the current conservation moment as a function of colonial legacy and post-independence decay (to varying extents depending on the specific path dependencies that have unfolded). In broad brushstrokes, colonial conquest was strongly associated with the rampant trophy hunting of iconic species. This much is clear from Nikolaj Bichel and Adam Hart’s 2023 book Trophy Hunting. The appetite for and scale of destruction is hard to fathom. But the logic of trophy hunting squares fully with the mindset of conquest. Motivated by a desire to show off a trophy (normally horns or tusks, but often entire stuffed bodies), hunters kill in foreign lands and expropriate the trophy back home to line the narcissistic display wall.

Whether the deeper motivation is informed by a perversion of the biblical instruction to “subdue” the earth is harder to ascertain. Either way, the desire to dominate rather than exercise stewardship through our “dominion” has resulted in extensive destruction. Eventually, hunters themselves recognised that administrative efforts would have to be made to conserve species lest they all be extirpated (and thus unavailable to hunt in the future). The establishment of national parks – legislatively protected areas – was not so much an exercise in conservation, then, as it was of creating a more sustainable means of future exploitation.

These efforts to create protected areas gave rise to what has become defined as “fortress conservation” – the imposition of fences to keep wildlife in and indigenous communities out. One intolerable outcome is that many community members living near national park boundaries have never been inside a park or experienced the tranquillity of pristine wildlife areas. It is not surprising that the sentiment among many is that governments care more for animals than they do for people.

It is not hard to see how this model, which displaced residents and dislocated them from their sources of livelihood, has generated fragmentation of both the social order and institutional arrangements that previously governed resource use. Contrary to the standard “tragedy of the commons” story, where individual resource acquisition incentives are incompatible with sustainable collective resource use requirements, local resource governance institutions were relatively stable and sustainable prior to colonial conquest. Ironically, colonial trophy hunting outside protected areas – which continues today under the banner of “sustainable use” – is highly susceptible to a tragedy of the commons. Each hunting concession lease owner has an incentive to over-exploit the determined quota; no owner expects that other concession owners will adhere to the quota; this creates an incentive to exploit more today in the expectation that the resource pool will dwindle tomorrow anyway.

Because pre-colonial institutions were distorted through the imposition of national parks, residents living near wildlife became susceptible to poaching incentives. Transnational organised crime syndicates could exploit a vast pool of disenfranchised community members. Poaching was bound to grow when demand for products such as ivory and rhino horn started to escalate, driven by growing consumption in the East following the end of World War II. Eggs are difficult to unscramble, and wildlife protection became dependent on those same institutions (protected areas) created as part of the colonial endeavour. As poaching intensified, protected area management had to increasingly resort to military tactics to defend parks against poaching incursions. In South Africa, this gave rise – post-2009 – to a “war on rhino poaching”.

Critics have rightly pointed out that securitising parks through this kind of “green militarisation” is likely to prove unsustainable. For one thing, the primary threat is often within the fence, not outside it. Corruption inside Kruger Park, for instance, has been rampant and requires a sophisticated response. Moreover, for every poacher shot or apprehended, there are hundreds of others waiting in the wings. Poverty is also not the only driver of poaching – many poachers are coerced (by gangs) into either poaching or infiltrating park structures. It is, therefore, critical to disrupt organised crime networks at the same time as defending park boundaries. There is growing recognition of this need, and some vital blows have been struck against powerful syndicates across the continent.

In the long run, conservation is not going to be successful unless it becomes more inclusive. In other words, those living near parks or near wildlife (in unprotected areas) need to have a direct interest in the preservation of wild landscapes. We need to make appropriate incentives available towards this end, and not only monetary ones. Preserving enough biodiversity to mitigate the worst effects of climate change will require massively expanding wild landscapes across the globe. Such efforts require the careful establishment of connecting migratory corridors between different protected areas, free from human encroachment. These corridors require conservation-compatible agriculture along buffer zones. Produce from these zones needs to literally feed tourism value chains, alongside direct ventures that benefit from “non-consumptive” tourism activities that avoid the intensification of commoditising our natural heritage.

South Africa’s recently gazetted Draft National Biodiversity Economy Strategy is an example of both what to do and what not to do. Some have lauded it as progressive, but they are deeply committed to the view that monetisation is inevitable, and even paying the entry fee to a national park, so their argument goes, renders one complicit in “monetising” wildlife. The plan envisages a massive expansion of contiguous protected areas (laudable) alongside pushing for increased big-five trophy hunting and reopening international trade in ivory and rhino horn (sub-optimal).

Those in favour of private wildlife commoditisation argue that it is the only way forward, and giving local communities a stake in the “wildlife economy” is the only means to fund conservation and break down fortresses. Typically, what is meant by “wildlife economy” is rampant commodification and exploitation through intensive breeding, trophy hunting, trading in animal body parts, and exploiting wildlife for game meat production.

This view is deeply rooted in the very paradigm that gave rise to fortress conservation in the first instance. It is, therefore, difficult to see how it could credibly take us out of the current conundrum. Community-based natural resource management (CBNRM) schemes in countries beyond South Africa sought to generate conservation funds for local communities through consumptive activities like trophy hunting. They have largely failed due to poor governance. I am convinced, however, that a deeper reason explaining their failure is the underlying idea that commodification solves all problems. It ends up paying pitiful wages, for instance, to trackers involved in trophy hunting, while the majority of hunting fees accrue to wealthy landowners who are often politically connected. In other instances, gangsters masquerade as “community trusts” and acquire hunting licences from the government at the expense of authentic local communities.

Finally, the idea that big-five trophy hunting and trade in products of endangered species can fund conservation is wrongheaded. It assumes that legal trade will simply crowd out illicit markets rather than merely providing a cover for them. Given that organised crime groups are already well-established in corrupt contexts, it is difficult to see how creating legal markets for highly scarce products will reduce poaching. This is especially the case if moves to legalise trade shift the demand curve outwards. The answer normally is that such trade will generate cash for local communities who have a stake in breeding, say, rhino, and incentivise preservation rather than poaching. However, poaching wild rhino remains far less expensive than breeding, especially if such breeding is done to avoid merely farming rhino intensively.

Preserving our natural heritage and expanding wild landscapes will require a fundamental reorientation of how we think about humanity’s relationship with nature. We cannot simply call for an end to green militarisation and fortress conservation without providing an alternative model. Similarly, we cannot resort to the fatalistic view that even viewing wildlife is a commodifying act, and therefore we should embrace the market. The latter reflects a naÏve expectation that the “marketisation of everything” will solve complex problems. It won’t, as history has amply demonstrated.

Dr Ross Harvey is a natural resource economist and policy analyst, and he has been dealing with governance issues in various forms across this sector since 2007. He has a PhD in economics from the University of Cape Town, and his thesis research focused on the political economy of oil and institutional development in Angola and Nigeria. While completing his PhD, Ross worked as a senior researcher on extractive industries and wildlife governance at the South African Institute of International Affairs (SAIIA), and in May 2019 became an independent conservation consultant. Ross’s task at GGA is to establish a non-renewable natural resources project (extractive industries) to ensure that the industry becomes genuinely sustainable and contributes to Africa achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Ross was appointed Director of Research and Programmes at GGA in May 2020.