Madagascar: a tale of two mines

The forsaken Ilakaka and coddled Ambatovy mining operations exemplify the problem and the solution

By Brian Klaas

In the early 1990s, only 40 people lived in Ilakaka, a sleepy village off the beaten path in south-west Madagascar more than 700km from Antananarivo, the capital of the rugged Indian Ocean island. The government took little interest in the village; it was no more than a blip on the map. But in 1998 the discovery of pink sapphires in Ilakaka brought a huge demographic change to the village. A year later, it was home to 100,000 residents, all seeking to “get rich quick” through a geological miracle. For the lucky ones, the discovery of sapphires was life-changing. Madagascar is one of the poorest countries in the world; an estimated 90% of its population scrapes by on less than $2 a day, so the attraction was obvious. The biggest, purest sapphires could fetch hundreds of thousands of dollars for a lucky miner. In the span of a few years, roughly half of the world’s sapphires were being extracted from Madagascar’s land. But every boomtown comes with busts. Most of the residents of Ilakaka have not been so lucky as to change their fortunes with gifts from the fickle soil of the region.

The earth is mostly grey and empty, and only every so often does it yield a burst of colour. The same is true of life in Ilakaka: it is mostly grey and empty. Mining operations in the town are completely unregulated. There is no formal company to work for and no union to join. The most common arrangements are between small-time employers and employees. Some miners receive daily in-kind payment, usually food, and agree to receive a portion of any profits from gems that they find with their employer, usually a Sri Lankan or Malagasy middleman. Others agree to receive $2 a day to guarantee their survival and support their families. But they forfeit the right to any share of the profits from any gems they find. If labourers in this category find a $1m sapphire, they still get just $2 a day. But then the employers do not really make a killing either. On the rare occasion that a lucrative gem is found, they hawk it to an array of traders, who are mostly from Sri Lanka or Thailand.

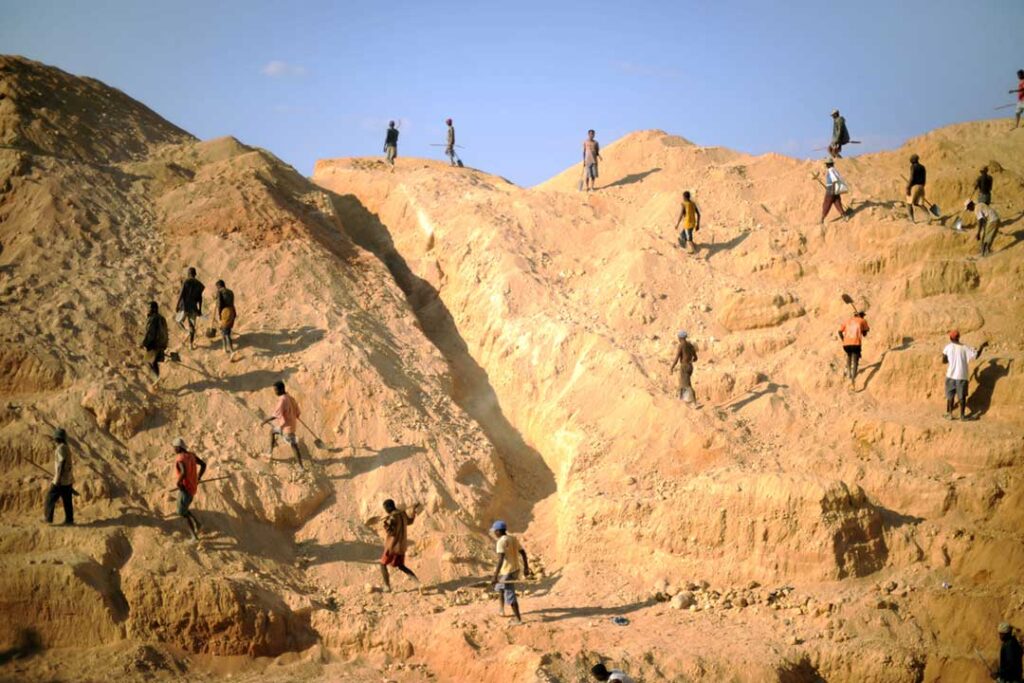

But at the point of purchase in Ilakaka the sapphire is still rough and unpolished and therefore worth less than it will be when it is sold on the world market. All of the sapphire clean-up happens outside Madagascar. This means that the mark-up and the profit come at the point of sale in Bangkok, London or Paris, or wherever the gems are bought, and does not reach the miners. Ilakaka is Madagascar’s Wild West. Life is dangerous. Untrained workers, hoping to make a quick fortune, scour land that might have sapphires hidden beneath its surface. Once they have picked a spot, they dig deep holes–up to 50m below the topsoil–with steel rods, searching for a sapphire-rich layer of rock, gravel and soil. Nobody insists that they reinforce these holes for safety. Nobody cares. As a result they routinely cave in, burying the miners alongside the sapphires they had hoped to find. Children, often expected to dig and search alongside their parents, are also killed in collapsed tunnels and caved-in holes.

A US government fact finding mission in 2008 suggested that up to 100 people die annually in these accidents. Even if the miners survive, danger lurks beyond the holes. Violence is rampant. Nobody keeps reliable statistics, but there have been countless murders as deals go awry or opportunistic thieves rob another luckier miner and kill him. Madagascar’s government tried to secure the area by deploying 50 gendarmes, but there were reports that the poorly paid police officers could be bribed into “loaning” their weapons to thieves and bandits. In other words, government-sanctioned armed foxes were guarding sapphire-rich Ilakaka’s hen house. The social costs are just as ugly. Today there is a smattering of primary schools in the region, but nothing for older children. Most of them are working with their parents anyway. A 2006 survey by the International Labour Organisation’s Programme on the Elimination of Child Labour estimated that 15,200 of Ilakaka’s 21,000 children worked on the mines.

Many of the others were working as domestiques (servants) or as child prostitutes for the roving labour supply. There are limited, if any, sanitary sites in the makeshift mining camps. Many miners do not have regular access to potable water. Respiratory infections, tuberculosis, malaria, diarrhoea and other easily avoidable diseases are common. The government of Madagascar has four labour inspectors in the region, whose responsibility should include monitoring labour conditions in Ilakaka, but they are based in Fianarantsoa, roughly a four-hour drive from the village. There is nobody to come to the rescue; there is just desperation and the perilous free market of gem trading. By contrast, Ambatovy mine, only 80km east of Madagascar’s capital, is far more regulated and safer, albeit far from perfect. Sheritt International, a Canadian mining firm, has invested roughly $7 billion in this mine, which extracts vast amounts of nickel. The mine employs 9,000 workers, of which about 90% are Malagasy nationals.

It is the largest single foreign investment in Madagascar’s history. Unlike in Ilakaka, Ambatovy’s workers are unionised. This is, of course, no guarantee of protection: five union officials from Madagascar’s General Confederation of Labour Unions were dismissed for sending a letter to the government denouncing the mine management’s practices. This was a warning shot to union officials and exposed the government’s willingness to take the international investors’ side over that of “lowly” local employees. But the union does agitate for much better working conditions for Ambatovy’s miners than those labouring in Ilakaka. In March the miners at Ambatovy decided to strike over the lax evacuation procedures in the case of emergencies, while also demanding better healthcare. The strike lasted two weeks and two days, but ended after a marathon 13-hour negotiating session (assisted by Madagascar’s government) that brought the miners back to work with modest concessions from Ambatovy’s management.

In April, the workers at the mine’s processing plant followed in the footsteps of the workers at the mine itself, reducing production for a short time. Again, the issues were resolved after government efforts to mediate. The mine is again operating at full capacity. The contrast with Ilakaka could not be starker. Not only are the workers in Ambatovy unionised, but they have meaningful recourse against the mine’s management if and when they feel that their labour is undervalued, or their working conditions are below international standards. Beyond that, the government ignores Ilakaka at best or is complicit in its horror show lifestyle at worst. It also serves as a productive mediator in Ambatovy’s labour issues. This is not surprising, as the loss of a $7 billion international partner would be devastating. In contrast, the weak administration in Antananarivo is largely unable to extract taxes from Ilakaka’s black market trade of gemstones. These two mining communities are outliers in Africa; most are not quite as lawless as Ilakaka and few are as regulated as Ambatovy.

But, at both extremes, each one is illustrative of the need for moral imperatives and good governance in the extractive industries. Governments have an important part to play in ensuring labour safety and enforcing baseline benchmarks for working conditions. Their failure to do so remains an unacceptable moral blight on the continent in the 21st century. It can be corrected easily with regulation. If governments refuse to do so, they should be held accountable by international donors. Unregulated extraction of mineral resources will undermine government efforts to harness natural resources with appropriate taxation–limiting the ability of African states to invest in their future. International pressure and strategic diplomacy should therefore focus on pressuring governments across the continent to clean up zones such as Ilakaka rather than letting them fester out of sight and out of mind. International investors also play a role.

They can and should be leaders in improving labour standards. If they lean on governments to accept abysmal working conditions, the firms might win short-term profits. But they will lose the long-term battle for sustainable African development, which affects the long-term growth prospects of these economies. Investors that do not care about regulation and labour are mortgaging the long-term health of their investments for short-term payoff s. Ambatovy’s practices are not perfect but the company has the opportunity to be a beacon that shines as much as Ilakaka is shrouded in darkness. Governments should apply social impact clauses in their permitting procedures to encourage high labour standards. Workers everywhere should have the right to decent wages, reasonable benefits, safe working conditions and recourse against management when those terms are not met. Africa is no exception, even though it is often treated as one. Until the Ilakakas of the world are brought into the formal economy and regulated, African workers looking for decent jobs will be like miners sifting through the soil: hoping to strike it lucky with a rare gem, but painfully aware that they are more likely to end up with dirt.