Togo’s elusive blue gold

by Blamé Ekoue

In Lomé, the capital of the tiny West African country of Togo, many citizens still fetch water from traditionally built hand-dug wells, water that may not be safe to drink. At Tsevié, a town located some 35 km north, women walk more than five kilometres every morning to fetch water in the nearby Haho river where goats, cows and other animals drink, wash and defecate.

Togo, a narrow strip of land, has copious water resources: rainwater, surface water in its three river basins and groundwater reserves. Its renewable freshwater resources (rivers and groundwater from rainfall) amount to 11.5 trillion litres, according to the World Bank’s latest figures.

These quantities are more than enough to quench the thirst of Togo’s six million citizens. The daily drinking water requirement per person is two to four litres, according to the UN. Each person needs 20–50 litres of water a day to meet their basic needs for drinking, cooking and cleaning. Another 2,000–5,000 litres are needed per day to grow the food one person consumes.

Togo easily has enough water for each citizen to use 5,000 litres a day. Its reserves stood at 1,868 cubic metres per person in 2011 (or 1.9m litres per person per year).

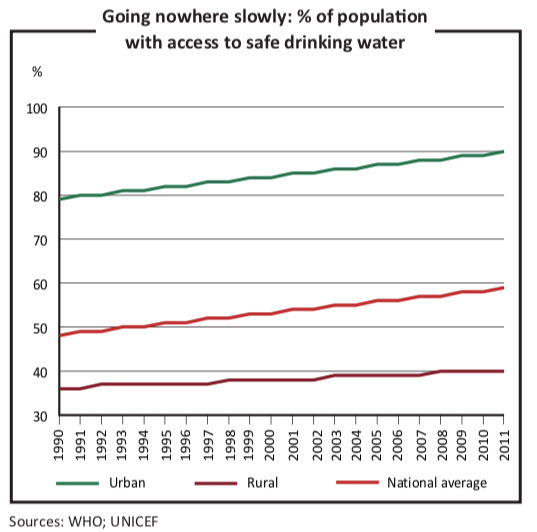

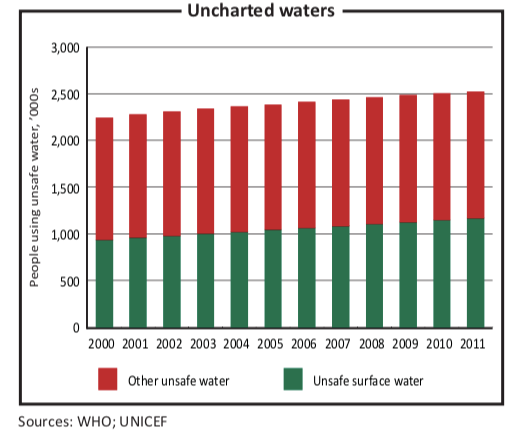

Despite these vast water resources, only 59% of its citizens had access to safe drinking water in 2011, according to the World Health Organisation and UN children’s fund. And state water infrastructure only supplied clean drinking water to 39% of the population in 2011, according to a government report. Government mismanagement and corruption are to blame.

In the past two years, the Togolese authorities, with the support of international financial institutions and other partners, have dug 860 hand-pumped water wells and constructed 20 small-scale water distribution systems that drill for water and pump it to the surface with generators. But this is still not enough to satisfy the population’s thirst. The quest for the “blue gold” goes on unabated on riverbanks in rural areas, where villagers share this precious resource with goats, sheep, pigs and other animals.

Togo is committed to reaching the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), eight time-bound and measurable targets to be reached by 2015, which include halving the proportion of people without access to safe drinking water and basic sanitation provided by state infrastructure.

In 2000, when the Millennium Declaration was signed, 31% of the population had access to clean water from state water infrastructure and 69% did not. To reach its MDG water goal by 2015, the government must expand its service to reach 66% of its citizens.

“Today we can provide drinking water to 44%,” said Nabagou Bissoune, Togo’s minister for water resources, referring to 2012 figures in a press briefing last May. With only two years remaining the country will find it difficult to attain these goals, he conceded.

Many believe Togo’s state-run enterprises are not well managed and lack transparency, particularly the state-owned water company, La Togolaise des Eaux, said Sena Alouka, a prominent Togolese environmental activist. “They are tight-lipped over accountability,” he said. “But if the company wants to prosper economically to attract more investors, there is a need to put into place some mechanisms for good governance. In this regard, they must opt for public-private joint ventures. This will enable the company to be more accountable and more efficient.”

Many civil society organisations have also become more outspoken and critical since July 2010, when parliament adopted the country’s water code. The code, which came into effect two years later, sets out a legal framework for the management, distribution and protection of Togo’s water resources. It also expressly recognises Togo’s water resources as public property.

There has been a slight improvement in the management of water resources, acknowledged Claire Quenum, president of Women in Law and Development (WILDAF), a local non-governmental monitoring and evaluating group. “Though things are changing gradually, we must put in place some mechanisms of good governance in ensuring that those in authority can be subjected to vetting if things go wrong,” she said. “And this must be done in an inclusive manner regardless of political affiliation. That is where cooperation between government and civil society organisations is important because we do work with people at the grassroots,” she added.

Corruption is another problem that has stymied improvements in Togo’s water distribution. After Togo’s successful multi-party elections in 2007, the European Union and other nations removed diplomatic and financial sanctions (dating back to 1993 because of democratic shortcomings), which opened the doors to new foreign aid and investment. In 2010 the World Bank and IMF gave the economy another boost through an initiative that led to the gradual cancellation of $1.8 billion, or 82%, of Togo’s external debt.

But the renewed flow of foreign aid led to increased malfeasance and corruption, which the government is now addressing with an inter-ministerial committee that regulates the management of water resources and sanitation.

“One problem with the donors is that they do not really monitor the effectiveness of the projects they finance,” said Ametepe Ablam, a Togolese lawyer. “Some companies managed by some barons of the ruling party made away with huge amounts without any accountability. But now that the authorities have set up the needed apparatus, every company must be vetted.”

Cocoa, phosphates, coffee and cotton are Togo’s main exports. Agriculture accounts for 45% of the country’s freshwater withdrawals, according to the World Bank.

But herders of goats, sheep and cows compete with small-scale farmers for this water and often fight over it. For instance, Togolese small-scale farmers from the Konkomba tribe frequently clash with Fulani herders from Burkina Faso in the northern parts of the country where the Oti River flows from Burkina Faso, traverses Togo and empties into the Volta River in Ghana.

The inter-ministerial committee has tried to heighten cooperation with neighbouring states to address these tensions. One example is a deal between Togo and Ghana to relaunch the Sogakopé-Lomé transborder water supply project. The project will draw water from the Volta River in Ghana to be treated at a plant near Sogakopé, also in Ghana. Water will then be pumped through an 82 km pipeline to a distribution tower in Ségbé near Lomé. Estimated by the African Development Bank to cost $119m in 2003, this project will attempt to offset seasonal water shortages in the two countries through the supply of drinking water to southern Lomé and Ghana’s bordering south-east Volta region.

The European Union has financed a programme to train employees at the water and health ministries and to help Togo reach its MDG targets, valued at 11 billion African Financial Community (CFA) francs (about $22m).

“The government needs about 300 billion CFA francs to cover ground in this sector if we want to reach the target by 2015,” said Francois Koami, president of Alliance of Media in support of Water and Sanitation (AMEA).

But more than money is needed. Giving people access to Togo’s abundant water resources depends on strong policy and laws, effective management of water use, distribution and storage and, most importantly, civic determination. Unfortunately, at the pace the government is going, it will be drop by drop.

Blame Ekoué is the Togo correspondent for the BBC and for Paris-based media house, ANA. He has also reported for Associated Press and Radio France International. He holds a BA in Communications from the Leader Institute in Lomé. Formerly deputy editor of the West Africa Revue, he has been a contributor to the Lome-based Business and Finance magazine since 2015.